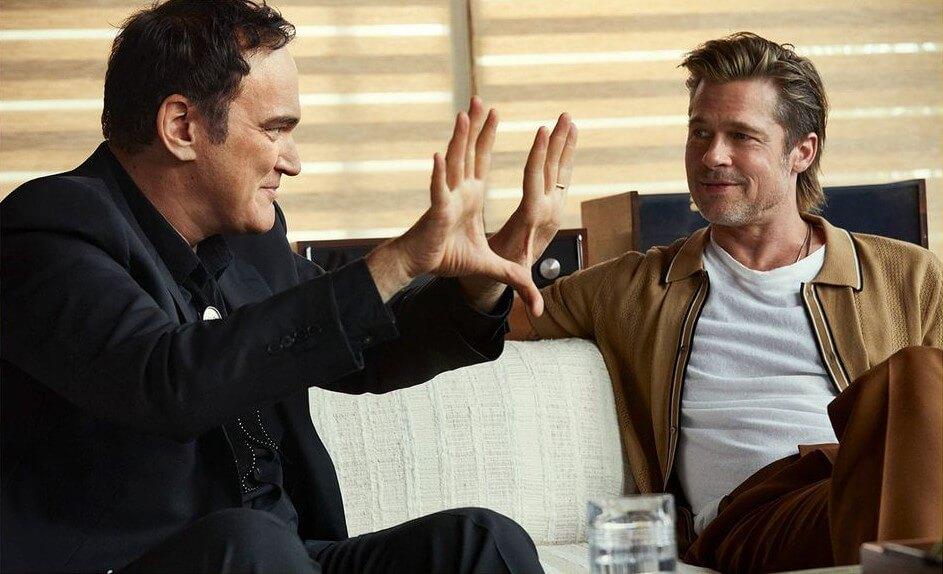

Quentin Tarantino, Brad Pitt, and Leonardo DiCaprio Take You Inside ‘Once Upon a Time…In Hollywood’

As the director unveils his highly anticipated ninth film, Esquire sits him down with his headlining stars for a provocative three-way Q&A about Hollywood past and present.

“HEY. HEY. GOT A SECOND?”

Quentin Tarantino is in my face. He’s smiling, polite. But still, in my face. Nose-to-nose like.

“Listen,” he says, and he starts fast-twirling his index finger in a tight circle, like he’s winding dental floss around it. “I’ve come up with a few questions that could be really good for you to ask.”

His voice is hushed, conspiratorial, but since this is Tarantino, it’s also stage-whisper loud. And naturally, the words tumble out of his mouth with an urgency I would, in any other encounter, describe as Tarantino-esque. But in this case, that’s redundant.

We’re on the patio of a house in the Hollywood Hills. A minute earlier, I was alone under the eaves, looking at Tarantino, Brad Pitt, and Leonardo DiCaprio standing near the pool, all of Los Angeles unspooling into the horizon behind them.

I’m waiting for them to finish being photographed so that we can talk about how they came together to make Tarantino’s new movie, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, and what they learned through that creative process.

“But here’s something important,” he says. “I don’t want it to seem like you are asking a question.”

It occurs to me that Tarantino is, in fact, directing me on how he wants me to deliver my questions.

When we spoke on the phone, Tarantino told me, “This film is the closest thing I’ve done to Pulp Fiction.” Think multiple characters (some real, some imagined) and story lines that are seemingly unrelated . . . until they are not. This film, Tarantino says, is also “probably my most personal. I think of it like my memory piece. Alfonso [Cuarón] had Roma and Mexico City, 1970. I had L. A. and 1969. This is me. This is the year that formed me. I was six years old then. This is my world. And this is my love letter to L. A.”

The story goes like this: It’s 1969, a year of tremendous upheaval, not just in America’s streets but also on the backlots of Hollywood. The original studio system, which has been a source of stability and structure for fifty years, is collapsing as the under-thirty counterculture rejects traditional plotlines and traditional leading men. Films celebrate the antihero and upend the definition of what a matinee idol looks like. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is a film that vibrates with ambition, with the entire cast performing at the height of their talent, inside a brilliant story.

It’s also a film that almost never got made. Mostly because Tarantino spent five years writing it as a novel before “I let it become what it wanted to become. For a long time, I didn’t want to accept it. Then I did.”

Pitt enters the living room and drops down in the center of a semicircle couch. Tarantino has already claimed the right-hand side. DiCaprio enters and sits down, and we’re off.

Michael Hainey: Brad and Leo, what attracted you to these roles? If I understand correctly, you are two of the only people who have read the entire script.

Brad Pitt: Which, in order to read, I had to go to Quentin’s house and sit on his patio.

Leonardo DiCaprio: I sat on the patio too!

What pulled you guys into this project?

LD: Well, first off, the chance to work with Mr. Tarantino. And certainly this time period was fascinating. It was this homage to Hollywood. I don’t think there’s been a Hollywood film like this—and by that I mean a film set in Hollywood and about Hollywood—which gets its nails dirty, getting into the everyday life of an actor and his stunt double. 1969 is a seminal time in cinema history as well as in the world. I loved the idea of taking on this struggling actor who is trying to find his footing in this new world. And his pal who he’s been with through all these wars in Hollywood. Quentin so brilliantly captures what’s going on in the changing of America but also through these characters’ eyes how Hollywood was changing. It was captivating when I first read it. The characters had the imprint of Quentin’s immense knowledge of cinema history. You are in awe of the detail, and you know it’s authentic. [Laughs.]

BP: It’s layers deep. Beyond any of my understanding. Even the title, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, is an homage, and it’s connected.

Quentin, what are you saying with this title?

QT: Well, there is a fairy-tale aspect, so the title fits pretty good. But this is a memory piece also. So it’s not historical fact per se. It is a Hollywood of reality—but a Hollywood of the mind at the same time. I was so happy with the title, but I was afraid to put it into the atmosphere. Whenever I referred to this project, I referred to it as Magnum Opus. A movie came out two years ago called Once Upon a Time in Venice. I go, “That was scary.”

BP: Once Upon a Time in Burbank . . . [Laughs.]

Brad, what attracted you to this script?

BP: Certainly the period is great fun. QT is the last purveyor of cool. If you land in one of his films, you know you’re in great hands. Quentin gives you these speeches, the kind that you wished you had said on the drive home, that you think of a day later. I felt the script was an evolution of Quentin’s voice. I mean, we know Quentin Tarantino as an auteur sending film in a singular, original direction. But I found this an evolution—and an amalgamation of what we loved about his other eight films.

QT: I didn’t try to do that, but it just started happening.

BP: And it felt really good-hearted, like warm-hearted.

LD: That is very true.

BP: And doing this with Leo was really cool and a rare opportunity. Then there was just the whole thing, where we all grew up with the lore of the lead actor and his stuntman. That relationship and craft. I mean, there are epic stories of these duos: Burt Reynolds had Hal Needham. Steve McQueen had Bud Ekins. Kurt Russell had his guy. Harrison Ford had his. These guys were partners for decades. And it’s something that is not the same in our generation, as the pieces became more movable.

LD: It’s also this authentic Hollywood story in the sense that our characters are the voyeurs of the majesty and glamour of Hollywood. We’re the outsiders. We’re the guys who are there day to day, trying to get the work. Brad and I are watching Hollywood change, but we’re in the grind. And we have this connected relationship where we have each other’s backs. That’s the perspective Quentin took, and it seems like these characters could truly exist.

Brad, how was working with Quentin on this different from working with him on Inglourious Basterds?

BP: It felt like walking right back in. I have an immediate comfort on Quentin’s sets. It’s the atmosphere. It’s the conversations we have, which are just fun. You know, we all kind of came of age in this industry about the same time.

LD: We’re all nineties babies.

BP: We all speak the same language and understand the same seismic events or minor events in our community. [Turns to DiCaprio.] One of my first jobs was guest-starring on your show.

LD: Growing Pains?

BP: When you were just starting.

It’s astounding to think you all hit at the same time. Quentin, you have Reservoir Dogs in ’92 and then Pulp Fiction in ’94. Brad, you have Thelma & Louise, A River Runs Through It, and Interview with the Vampire in ’91, ’92, and ’94. And Leo, you do What’s Eating Gilbert Grape in ’93. All three of you have been on top in Hollywood for a quarter century now.

QT: Brad’s even in True Romance in 1993. The first script I wrote! And he almost steals the show in the third act. [They all laugh.]

BP: There is an immediate comfort, stepping into Quentin’s dialogue. It’s why actors want to work with him—you should have seen the line of people trying to get into this film. Offering their services, just to be a part of this thing, even just for a day.

Quentin, anyone I talk to tells me how joyful your sets are. How if you call for another take, you’ll say, “Let’s do it one more time! Why?” And then the entire crew yells . . .

QT, BP, LD: “ . . . because we love making movies!”

BP: It’s that great spirit. True.

LD: His sets are so magnetic. You don’t walk onto sets like this anymore, where everyone has respect for the process. There’s this celebration of a way of making movies that has slowly become an antiquity in this industry. Quentin puts a tremendous amount of thought into making these characters come to life, making the authenticity of the period come to life. There’s also this freedom—an energy—we feel on his set. And that is: taking the time to Get. It. Right. At all costs.

BP: And to know when you got it.

Quentin, what did Brad and Leo find in the characters that you hadn’t put on the page?

QT: Quite a bit. Brad was already aware of the history of different actor-stuntman teams. So he immediately was like, “Oh, this is like Steve McQueen and Bud Ekins.” Which means, you know, Leo’s character is sort of the poor man’s McQueen.

BP: Which would make me the poor man’s Bud Ekins.

QT: [Laughs.] Brad immediately thought that the idea was hip and really wanted to lean into it. But there’s an interesting thing as far as Cliff is concerned: We follow three different people in Hollywood, and they represent the three social strata of the town. We follow Sharon, who is truly living the Hollywood life. Then Rick, who is doing better than he thinks he’s doing. He has a house, some money, and he’s still working. Then Cliff represents a guy who has dedicated his entire life to this industry and has nothing to show for it. [DiCaprio and Pitt laugh.] He is part of Hollywood, but he lives in Panorama City in a trailer. Make no mistake: Hollywood is his life, but he is not a citizen.

And there’s a neat aspect when it comes to Cliff and then to Brad, developing Cliff’s character: He and I are very similar in age, so this is an equal memory piece for Brad. In 1969, we were both five, six years old. We both remember the shows that were on TV and what was on the radio.

But with Leonardo, who didn’t grow up in the same era as Brad and me, I needed to find references for him. And that gave it a freshness, watching Leo watch old western TV shows I’d given him. Then I’d invent a movie that Rick could have starred in, like The 14 Fists of McCluskey, which is like a poor man’s Dirty Dozen. I said to Leo, “If Rick’s rival, Steve McQueen, does The Magnificent Seven, Rick is the kind of guy who would have been in the third sequel, as the second lead.”

You’re like Monte Markham, who also played Death in the first remake of Death Takes a Holiday.

BP: Yeah, those remakes should have stopped there. [Pitt starred in Meet Joe Black, the third remake of Death Takes a Holiday.]

Quentin, you’re touching on something. In acting, there’s how the character is written, and then the experiences or memories an actor brings to the character. Brad, what did you pull from your life?

BP: I had growing-up flashbacks, because the flavors were all there. For instance, in the movie, Cliff lives next door to a drive-in theater. In Missouri, I grew up a few streets over from the drive-in theater, and I would go hang out at my friend’s house so we could watch movies from his backyard.

Leo, what did you bring from your life?

LD: I grew up in this industry, and I have a lot of friends I’ve known since I was thirteen who are actors. I’ve seen the trials and tribulations. Some of the struggles I immediately recognized—the search for your own identity and the search for success in an industry that rejects 99 percent of actors from this elite class of being able to choose your own work. I have many friends in that situation. They all love moviemaking, but do a lot of them feel like they belong to the club? Rick, his whole life is wanting to belong to that club.

But what I really loved about this movie is there’s a lot of love in the story of Cliff and Rick’s relationship. Because through all of this, they are like a family. They’ve created a family unit and a connection that’s going to let them survive the stomping of their dreams.

I mean, this is a story about guys who act in westerns, at a time when the western—which has always been a metaphor for American manhood and the idea of the rugged individual—is totally changing. And here you are, Rick and Cliff, in a period piece that riffs on an essential dynamic of the western: the duo.

QT: One of the things that Leonardo did—my prose was telling him a lot of the backstory—was he said, “I need a little more to play.” [Bangs table.] He said, “I need to act through something.” In talking about different actors of that era, I said something that intrigued him. I brought up—I think I can say this—Pete Duel.

LD: Oh, yeah.

QT: It started when Brad brought up Alias Smith and Jones [a western on ABC, 1971–73], and we both loved it when we were kids. As we were talking, it occurred to us that because of that show, it was the first time he and I had ever heard of suicide. In real life, Pete Duel, who played Hannibal Heyes, killed himself.

BP: I remember I was at my grandma’s house when I learned this. And I remember walking into a dark bedroom. It was a little tiny house. I went into the bedroom where it was dark and I burst into tears. I was so upset.

LD: I remember your conversation that day. I had no idea about the show and the actors, but you both said you had that exact same reaction.

QT: The fact that we both learned about suicide because of Pete Duel at age eight or whatever was . . .

LD: For me, that made it this really strong reality. And having also seen that happen with some of my contemporaries in the industry, how that wear and tear and constant disappointment can lead to that. I really wanted to infuse at least the feeling for the audience that suicide is an absolute possibility for Rick.

QT: From us talking about it, we realized why Pete Duel did it. In retrospect, he was drinking to self-medicate. So then we thought: Maybe Rick has a drinking problem. I had not written him in that way, but there always was this crazy swing of his emotions. Now there was a rooted cause, and that was the one Leo responded to. [Claps hands.]

Leo, there’s a scene where the child actor on your western, a girl, phones you when you are in a bad place. It is a poignant moment.

LD: Very. Not to define Rick’s journey, but it’s a journey not only of acceptance but of appreciation. When you are in his position, constantly looking for that foothold to stardom and doors keep shutting in your face, after a while you start to realize: Can I be happy where I am? Is there satisfaction in not achieving that goal? It’s a journey for Rick of his dreams constantly being trampled on, the effects of questioning himself on an everyday basis. Self-hatred. But can he get to a place of acceptance and appreciation for being in this industry? Is there any celebration of that, or is it just a constant source of disappointment? That’s the arc we were going with for Rick. But like I said, it’s Quentin’s celebration of this industry and all those who kept at it, even if all those dreams they had as a young spitfire didn’t come to fruition.

You touched on a theme a minute ago. On the surface, this is a film about actors in 1969, dealing with change in Hollywood. But what is powerful and universal is that, at the root, this is a story about two men battling forces that many men are confronting right now. What happens to me when I am in the middle of my career, in the middle of my life, and the industry I am working in doesn’t want me, or the job I have had for decades, it’s changing, or going away? Can I reinvent myself?

LD: I think you said it basically right on.

BP: Exactly. Who am I now? Where’s my meaning?

QT: Rick comes to town in ’55. He’s a young, good-looking guy. He thinks, Hey, I’m in Missouri. Let me get out of here and go where good-looking guys make money: Hollywood. I’ll get some tight jeans and hang around Schwab’s drugstore.

BP: That was me in ’86. [Smiles.]

QT: Hey, and it worked, too. Good on ya!

QT: But the thing is, Rick was sold a bill of goods everyone else was sold. To be a young leading man is to be macho and masculine and sexy and handsome and chiseled. And that’s how you got on a western show back then.

BP: And everyone came from that. Burt Reynolds. Clint Eastwood.

QT: All those guys. Now, in 1969, the new leading men are the exact opposite. They are skinny, shaggy-haired guys. And it’s the hippie sons of famous people. So it’s Peter Fonda. It’s Michael Douglas.

What’s fascinating—there is the rise of the pretty leading man, but there is also the rise of the anti–leading man. Dustin Hoffman plays Ratso Rizzo in a corrupted western, Midnight Cowboy. And then, who is the complete embodiment of the new anti–leading man? Charles Manson! He’s hairy and charismatic and young. Plus, he gets the chicks. And he literally steals the old dream factories from these guys; he’s living on an old movie set.

BP: Right! Well put, well put.

QT: In the film, there’s a sequence that takes place on Spahn Ranch. Through the whole movie, we’ve been hanging out on real Hollywood-western soundstages where phony versions of this kind of masculine drama are being played out for cameras. Then we end up on Spahn Ranch, on this dilapidated western backlot, and those masculine rituals are played out—but this time with real-world consequences, and no one’s acting.

Brad, there’s a great moment in the film that embodies Cliff. If Rick can never see outside himself, you are a guy who’s more aware of the wider world. do you see Cliff?

BP: He’s at peace with his mac and cheese. Even if he doesn’t have milk. He’s content with his place in life. Pretty thrilled just to be alive that day. I just felt like he would be all right wherever he landed. He would figure it out. He isn’t asking for that much.

LD: As I’m thinking about it, I’ve had these relationships in the industry too. You need your support system. You need that guy you can sit there and watch TV with and not say a word with for five hours. You need to know somebody is there. When we were doing the movie, my relationship with Brad clicked. It was very early on where he improvised a line and it changed everything. In the scene, as it was written, I’m coming to set hungover and I am basically getting my fate handed to me, discovering what my future is going to be in this industry. And I’m really down. And in the scene, Brad ad-libs. He just comes out with this line: He looks at me and says, “Hey, you’re Rick f**ing Dalton. Don’t you forget that.”

QT: That was a thing Brad just said—and it ended up becoming a thing.

BP: True story, this was probably early nineties. I was on set and I was whining about something and lamenting something. I was pretty low. And this guy was basically saying to me, “Get your head up, hold your head up. Quit your whining. You’re Brad f**ing Pitt. I would like to be Brad f**ing Pitt.” It did me a favor. I needed to hear it. That day, I flashed on that. The way Quentin’s scene was constructed, it reminded me of it.

Speaking of the nineties, as we said, you guys all popped at the same time. And what’s interesting is, yes, the business is always evolving, but what courses through the streets of Hollywood is eternal. The insecurities, the neuroses, that never changes. Again, you all have twenty-five years of winning the lottery. So I’m curious: Are there other things that remind you of where you are right now in your own careers?

LD: I’ve been listening to podcasts about the history of Hollywood, the transition from silent films to talkies, the advent of television, the musicals in the sixties, the directors’ era of the seventies. And now we’re talking about streaming services. I don’t want to act as if I’ve been around since silent cinema, but I see this as a huge shift in the way movies are going to get done, what gets financing. The studio system has tons of content, libraries of things that they can make movies of, but in a lot of ways they are hemorrhaging. They’ve become—much like in the twenties—these corporate empires that have taken over the artistic vein of moviemaking. We’re now in an era when there’s a flush of cash into streaming. But with an overflow of content, there’s a lot of garbage out there. Now I do see a lot of chances being taken for story lines, certainly documentaries, giving some artists opportunities to make out-of-the-box story lines that I don’t think ten years ago would have been possible. But these types of films that Quentin is doing are also becoming endangered species.

BP: No question.

LD: I’m not saying celebrate this movie, but let’s celebrate filmmakers who are still holding on to the craft of making movies, and let’s hope that in that transition into whatever this is going to be, this type of filmmaking will still exist. There are some dark ages coming up.

BP: The positive of the new landscape is you see more people getting opportunities. But I see something else happening with the younger generations. I was dismayed at how many twenty-year-olds have never seen Godfather, Cuckoo’s Nest, All the President’s Men. And they may not even get to see them. I’ve always believed every good film finds its eyes, inevitably. But there’s a shift in attention span. I’ve been hearing from newer generations that they’re used to something shorter, quicker, big jump, and get out. And the streaming services work that way; you can move on to the next one if you’re enticed. What I always loved about going to a cinema was letting something slowly unfold, and to luxuriate in that story and watch and see where it goes. I’m curious to see if that whole form of movie watching is just out the window with the younger generations. I don’t think so completely.

QT: It requires the right kind of movie—one that hits the right kind of nerve where it becomes a conversation. It used to be movies were the pop-culture conversation and it was much rarer for a TV show to break into that place. But now that’s where it is.

Brad and Leo, you play these guys who are in the middle of their careers, and you’re in the middle of your careers and your lives—

BP: The middle—you’re being generous. [Laughs.]

When you look back at the beginning of your careers, how do you think you are different from when you broke into Hollywood?

LD: The first years are seminal. At that point it just becomes about opportunity. And in a weird way, I really connect with myself as a young man trying to get into the industry. Growing up in L. A., in Silver Lake, was the only reason I became an actor. Had I lived anywhere else, my parents would not have [laughs] picked up shop and moved—it was the sheer proximity to auditions. But once I got my foothold and I got that one movie, I said, “I’m doing movies now. I’ve been doing television and here’s my shot.” Any young actor I’ve ever spoken to, I say, “The first thing you gotta do is learn as much as you possibly can about the history of what has been done in the industry.” If you’re coming here and want your shot, then you need to learn about cinema’s past. ’Cause there have been some performances in films that probably can never be duplicated.

Well, you can steal from them too.

LD: My attitude is the same as when I started. When I talk to these two guys, it’s like, we know we were given that one shot and we do not want to disrespect that opportunity, which is why we’re just trying the damn best we can to make the best things we can. Because we understand that it is fleeting. Tastes change; culture changes. And I feel very blessed to have gotten that ticket to be able to do movies. So I feel very connected to that fifteen-year-old kid who got his first movie. And that hasn’t changed.

BP: I feel the same. It’s always been about quality. In the beginning it’s wild, and it’s loose, and it’s fun—you’re chasing, you’re chasing, you’re chasing. And you’re seeing what opens, and certainly you’re experiencing a lot of doors that close. But you just refine your craft. When I think of myself then and now, as far as the approach, it’s just a refinement of craft. Becoming a craftsman after a few decades of doing this. It’s all in service to story, and along the way you gain more wisdom and knowledge about story. But as far as an actor’s approach of being able to free yourself to see what you discover at the moment in the scene—you can just get there quicker, you know? Listen, the first few years on sets are just trying to block out the forty, fifty people who are standing around, and the lights, and the cables, and the cameras, and it’s a very foreign environment. Over time it becomes a home. And it becomes your community.

If you were to give Rick and Cliff advice, what would it be?

LD: Stop drinking! [Everyone laughs.] I watched a whole bunch of old films to prepare for this movie, and somewhere along the line I watched Gun Crazy [a 1950 film noir] and I was like, “Wow!” It was the seminal independent film where people didn’t have all the opportunities that Orson Welles would have had at the time —and I think about people working with some not-huge stars, a director who was pretty damn good but hadn’t made anything unbelievable. And with all the chips stacked against them, that combination of ambition got together to make something that was a phenomenal piece of art. And that’s what I would tell Rick: There’s always a shot. Maybe not quite the opportunities that you had hoped for, but there’s always a shot to do something magnificent—and to get out of that story that you have in your head that keeps playing like a computer virus, that story that says you’ve been screwed over by the industry, by society, by the changing of times.

QT: But it can all change in a moment. Three years or four years after the movie takes place, think about where Rick could be. The thing is, you get one audition and now your life is different. I’m always curious when I talk to actors about the one role that started everything. Brad, I remember I asked you, “What was it like when you auditioned for Thelma & Louise?” And you said, “Actually, another guy had the part.”

BP: Two. The first left to do another film because he got offered a lead, and then the second guy fell out. I think it had something to do with chemistry. But I don’t know for sure.

QT: But I am always curious about: Okay, this moment is going to change your life, but you don’t know it. It’s just one of four auditions you’re doing that week.

I want to hear about the structure of the film. It takes place over three days. That’s it.

LD: It was hard for me to wrap my head around that concept, because I don’t think I’ve done a film where the narrative takes place over just a couple days. We were given this incredible backstory. Quentin literally handed us our character’s life and we discussed it, and there were some things we agreed with and didn’t agree with, but we were given this road map of who these guys were. All that character history naturally infused its way into these two days in a really organic way. Stuff didn’t need to be explained. It was just there in the gestures, and there in the relationship. Usually, I’m like, “Let’s explain everything about the character. . . .” Quentin’s like, “No, this is just two days. We’re going to get glimpses of Rick’s condition and what Rick’s mentally and emotionally going through.” It’s the audience filling in the gaps that makes this movie, I think, very courageous. But doing a film that’s set over only two, three days? I don’t think I’ve ever done before. [Looks to Pitt.] Have you done it?

QT: Well . . . Titanic is only a couple days. Right?

LD: [Goes silent. Then:] Truuuuue.

BP: How does it end? [Laughs.]

LD: [Laughs.] I stand corrected. I guess it is.

Let’s talk about expectations around this film.

BP: I don’t tend to think that way. For me, it’s the experience of the film. And when you’ve had an experience that enriched your life in a way, when you know there’s good work on the table, and when you know you’re in great hands . . . then you know it’s going to be something that you can get up and feel good about. Where things land afterward . . . I think all good films find their place.

LD: I heard some of my friends talk about it after they saw the trailer, and they were like, This is exciting, because it’s a throwback to the type of cinema we’ve been yearning for. I recently went to a couple movies, and I saw seven trailers. I felt like I sat for fifteen minutes in this intergalactic world of people jumping in and out of different realms of reality and then dragons. [Laughs.]

You guys have lived in this town a long time. What six degrees of weirdness do you have?

BP: I remember back in the early days I hung out with Brandon Lee. He drove a hearse and lived in Echo Park. We went out one night and everyone else had peeled off, and we ended up back at his place and it was like six in the morning. A real, you know, drunk and stony night, and he proceeded that night to tell me how he thought he was going to die young like his dad. And I just chalked it up to, you know, stony 6:00 a.m. talk. Then he got The Crow the next year.

LD: I have one. One of the most ominous and sad ones. I grew up revering River Phoenix as the great actor of my generation, and all I ever wanted was to have just an opportunity to shake his hand. And one night, at a party in Silver Lake, I saw him walk up a flight of stairs. It was almost like something you would see in Vertigo, because I saw there was something in his face, and I’d never met him—always wanted to meet him, always wanted to just have an encounter with him—and he was walking toward me and I kind of froze. And then the crowd got in my way, and I looked back and he was gone. I walked back up the stairs and back down, and I was like, “Where did he go?” And he was . . . on his way to the Viper Room. It was almost as if—I don’t know how to describe it, but it’s this existential thing where I felt like . . . he disappeared in front of my very eyes, and the tragedy that I felt afterward of having lost this great influence for me and all of my friends. Just to be able to have that, always wanting to just—and I remember extending my hand out, and then . . . Two people came in front and then I looked back, and then he wasn’t there. [Pauses.] I actually flew later to New Orleans to meet about Interview with the Vampire to play the part Christian Slater ended up playing.

BP: I’ll tell you one of the greatest moments I’ve had in these however many years we’ve been at it in this town: getting to spend two days with Burt Reynolds on this film.

LD: Yeah.

He was originally cast to play George Spahn, correct?

QT: Yeah. The last performance Burt Reynolds gave was when he came down and did a rehearsal day for that sequence, and then the script reading. And that was really amazing. I found out from three different people that the last thing he did just before he died was run lines with his assistant. Then he went to the bathroom, and that’s when he had his heart attack.

Brad, what do you remember about those days with Burt?

BP: Well, you’ve gotta understand, for me, growing up in the Ozarks and watching Smokey and the Bandit, you know, he was the guy. Virile. Always had something sharp to say—funny as sh*. A great dresser. Oh, man. [Laughs.] And I had never met him, so being there with him reminded me of how much I enjoyed him as a kid. And then getting to spend those days with him in rehearsal, I was really touched by him.

LD: And for that matter, you know, Luke Perry! [Perry plays Scott Lancer, another fictitious TV actor.] I remember my friend Vinny, who is in the film as well, we walked in and we both had this butterfly moment of like, “Oh! That’s Luke Perry over there!”

BP: “That’s Luke f**ing Perry!” We were like kids in the candy shop because I remember going to the studios and [Beverly Hills, 90210] was going on and he was that icon of coolness for us as teenagers. It was this strange burst of excitement that I had, to be able to act with him. Man, he was so incredibly humble and amazing and absolutely committed. He couldn’t have been a more friendly, wonderful guy to spend time with. I got to sit down and have some wonderful conversations with him. It was really special.

QT: I went to the memorial, and three days earlier I had finished cutting together Luke’s last scene. It’s making me think: Grunge bands loved Reservoir Dogs. I think it was just a good tour-bus movie. Kurt Cobain was this huge fan to such a degree that I’m thanked on the third album. And I’d never met him. His people called me up and said, “Hey, would you like to get together with him?” And I go, “I’d love to, but I’m in preproduction on Pulp Fiction, so maybe at some point afterward.” But he never made it.

It reminds me, years ago I interviewed Sylvester Stallone. And in his library, I see this little piece of paper framed on the wall. It was a letter that said something like, “Dear Mr. Stallone, I want to congratulate you on your Academy Award nominations for Rocky. Signed, Charlie Chaplin.” It turns out, until Stallone was nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay and best actor for Rocky, only two other people had been nominated for an Academy Award for both writing and starring in a film: Orson Welles, for Citizen Kane, and Charlie Chaplin, for The Great Dictator.

LD: No way!

BP: That’s amazing.

This was 1977. So I said, “Did you meet him?” And he said something like, “It was so stupid, you know. I’m young and thinking, There’s time for that. But six months later, he was dead.”

BP: Wow.

Stallone said it was one of the great regrets of his life, not grabbing the moment. Isn’t that part of what the film is about, making the most of the time and being grateful? Because you never know what’s going to change in your life?

LD: Absolutely.