He’s the face of two blockbuster movie franchies, but Orlando Bloom’s current priority is a small set piece known as family life. It’s a role he loves.

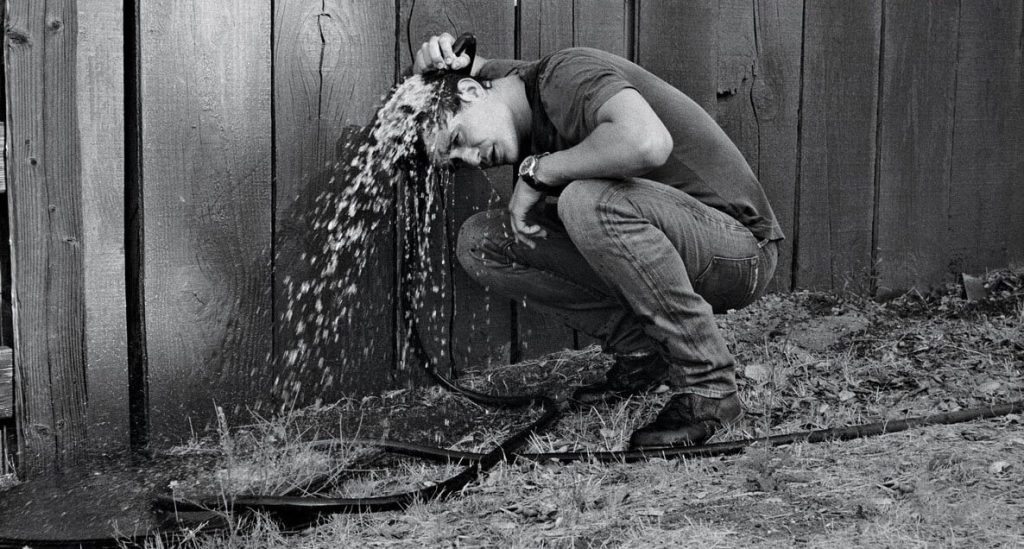

0rlando Bloom dangled three stories above the ground for one frozen, unbearable second. It seemed as if there must’ve been a safety net, a way out. But this wasn’t a movie. It was real life. And it might have ended right there, at age 21. “It was a ‘holy s*’ moment,” the actor says today. He remembers looking down and realizing, “There’s nowhere for my feet to go!”

Bloom fell.

And everything went black.

BLOOM, NOW 34, tells me this and other stories in the remarkable quiet of Griffith Park. It’s peaceful as we sit outdoors at a low-key cafe discussing the differences between real life and make-believe. Bloom works hard at make-believe. He also lives hard.

The man I meet today isn’t the same balls-before-brains lad who once thought it might be a good idea to shimmy out onto a roof between two buildings so he could bypass a locked door. (I’ll just step over to that window ledge…)That’s how he used to, uh, hang with friends in his native England. But as he tells me about his fall and several other scary events from his very real and occasionally insane offscreen life, I find myself picturing the stories as mini-movies. Bloom’s life is packed with this sort of drama, and he also manufactures it on the job.

Bloom is in the business of creating larger-than-life, big-boom stories for mass consumption. He played a hero in two of the biggest escapist romps of all, Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean. He has another go this October in The Three Muskateers, a new take on the Dumas classic (if Dumas wrote in 3D).

“People want to step out of the everyday routine of their lives and enter another world where they can go ‘wow,'” he says. “Believing you’re something that you’re not excites the mind and the imagination. And it’s hopeful. As you clock out the years and life moves on, you look around and ask, ‘What’s new? What’s exciting?’ We’re born, we’ll grow old, we’re going to die, that’s the only thing we know for sure. How can I spice up my life in the meantime?”

Bloom dedicates his free time to real moments that put him at risk, or force him to confront his own limitations, or simply take him to another level.

THE THREE-story fall broke his back. The doctors were doubtful he’d ever walk again. Twenty-one years old; no mobility.

“I’m grateful for it,” he says now.

Bloom has said that this period was “the making of me,” and in many ways it was. Being laid up, not knowing how the rest of your life will play out-or even worse, knowing exactly how it’ll play out if you don’t fight for a different outcome-is one very real, very difficult stretch of time. A movie would handle this period through a montage suggesting the passage of days. Bloom lived every second of it.

He had surgery to install enough screws and plates in his spine to hang a door. He rose. He rehabbed. He walked. And, amazingly, less than 18 months later, he was on a horse in New Zealand, firing arrows at the Uruk-hai. He would swashbuckle through the next decade in two fantasy juggernauts (Rings and Pirates), a Homer epic (Troy), and Ridley Scott’s Crusades tale (Kingdom of Heaven).

Years after his surgery, Bloom still pushes to keep himself healthy. “I’m always working on my back,” he says. “It hasn’t prevented me from doing anything. But it’s a constant reminder.”

Pilates is a mainstay for him, as he needs a serious core to support his back through all his activities. He also lifts weights regularly, dabbles in yoga, recently discovered tennis, and mountain bikes with buddies. Over the years he’s broken ribs (three), both legs (the right while skiing, the left in a motorcycle crash when he was 17), his nose (rugby), wrist (snowboarding), and skull (cracked, three times).

Bloom says his swordplay creates onscreen moments “that last in people’s minds.” Meanwhile, each broken bone and close call is a moment that lasts in his own.

Bloom tells me he fancies things on two wheels. He loves his motorcycles (he pulled up for our interview on a vintage 1963 BMW), but he loves his mountain bike even more. In a moment, he’s telling another tale and I’m right there with him, flying down a steep canyon trail not much wider than the tire of his bike. A death drop plunges off on the right. And he feels himself leaning too far that way.

“I bike at least a couple of times a week with a good crew between 2 and 5 hours of riding depending on the day. Seventeen to 30 miles, 2,500 to 3,500 feet in elevation, in a loop. Amazing hills around here.”

That’s when Bloom describes the runaway bike scene. Since the birth earlier this year of his son, Flynn, riding isn’t the same. Bloom is a father now. Which makes these mountain-bike jaunts a complicated matter.

“When I’m riding a technical singletrack and there’s a drop…” He gestures to describe the clifflike view on one side. “If I’m not fully focused, in my head I feel like I’m going to veer off, and I actually start to drift that way.”

These are real moments of doubt. They’re new and disturbing. The question is, how do you beat them? “I call them my mind critters. Can I defeat myself? I really like going downhill on a mountain bike, and if I just feather the front brake and let it roll, I’m fine. But if I’m not in that zone and I clutch that brake, boom, I’m over the handlebars. Or worse.”

And then he nails the explanation of why he still does it. He’s seeking “anything that brings me into my body and keeps me present. As opposed to out of your body, which is what we do the rest of the time. The world throws out of your body, especially the cyberworld.”

The key for Bloom nowadays is concessions. “I pad up. I estimate it’s saved me tens of thousands of dollars in medical fees. I do fly quite close to the wind.” (Though he admits he whispers, “safety first,” to himself while he does it.)

After all, he has a son (and a wife, the Australian model Miranda Kerr) at home. “Fear is not a friend of mine,” he says. “But it’s something to have a healthy awareness of.” Ah, but so is a healthy sense of risk. “I can’t stop living. It would ruin my creativity, the person I am.”

IN ELIZABETHTOWN, THE 2OO5 Cameron Crowe film, Bloom utters one of my all-time favorite movie lines: “Success, not greatness, was the only god the entire world served.”

I have to ask: Does he agree?

He bursts out laughing. Because he knows what I’m really asking. He’s had success, but has he achieved something great? “That’s a tough one. To an untrained eye, yes, success is what people aspire to and only success.” Then he pauses and leans closer. “The thing is, success can allow you to try for greatness, can give you an opportunity to take a chance on something. I’m very blessed to have the success that I’ve had, and that’s given me so many opportunities to work on being great.”

Maybe this highlights the difference between ordinary men and the few who achieve the extraordinary. One guy drifts from escape to escape; the other risks the fall. There’s nowhere for my feet to go.

Bloom’s home and family give him a place to land, but he also has the wisdom and skill to know when to let his feet dangle. That’s what the rest of us have to work on – living big within our own lives. It’s not a bad formula for living, and Bloom sums it up before riding of into the fading L.A light. “Grateful for the last,” he says, “looking forward to the next.”