How Dominic Monaghan snapped out of his hobbit depression and found himself Lost.

On a hilly Hawaiian road, the centuries-old trees tower over the tarmac, forming a green pavilion that dwarfs the Toyota Prius driven by twenty-eight-year-old Dominic Monaghan. He interrupts his anecdote about fleeing from Paul McCartney at an Oscar party and marvels at the verdant world around us. “Isn’t that great?” Monaghan says with a grin. “It’s like the Shire.”

He spent almost two years in New Zealand filming the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Now he’s part of the ensemble on Lost. Charlie is a pleasant bloke trying to shake off some of the darkness of his past. That description fits Monaghan as well.

Monaghan was born in Berlin to British parents who moved there to work in support roles to British troops: his mother, Maureen, as a nurse, his father, Austin, as a science teacher. “Nobody in our family had anything to do with acting,” says Austin. “We thought it was a pipe dream.” Not Dominic. “When we were kids, I was always convincing my brother to do little dramatic things in front of my mum and dad,” he says. “I always wanted to be an actor, but there was an embarrassing element to it. Maybe it was from this English stereotype of ‘if you’re an actor, you’re a homosexual,’ which is a strange thing.”

When Monaghan was eleven, his family returned to Manchester, England. “Manchester’s a rough place,” he says. “It’s guys walking around in thick anoraks in the pouring rain, smoking that last cigarette and jonesing for a fight.”

Monaghan lost his virginity at age fourteen: “It was very disappointing, almost forgettable. I remember having to sit down a couple of years later and say, ‘Who did I lose my virginity to?’ In hindsight, it screwed up some of my attitudes about sex. I would like to go back and make it about exploring an amazing new adventure instead of getting it over with.”

When Monaghan got into trouble at school, he could usually talk teachers out of punishing him, but his charm didn’t help him when he got arrested at age eighteen — for stealing a cheesy horror movie from a video store. “Not even a good movie,” he moans. “I didn’t have the brains to steal Apocalypse Now.” He attempts an explanation: “I had been drinking all day.”

Meanwhile, Monaghan was appearing in local theater productions and working on his own scripts. They were intended, of course, as starring vehicles for himself. They featured lots of monologues by likable rogues — “always with a twinkle,” he says. In the middle of his first year at the College of Manchester, he auditioned for the TV show Hetty Wainthropp Investigates; when he was cast, he left school to take the job. “We had a big party at home,” his father says. “I remember thinking that this was possibly what his career might amount to.”

Hardly. The series lasted two years; after that, Monaghan did a couple of small films and some London theater. He also auditioned, via videotape, for the role of Frodo in Lord of the Rings. When the producers had trouble casting Merry, they returned to those Frodo tapes. Producer-screenwriter Fran Walsh remembers, “He had the flu and spent some time apologizing for the gravelly sound of his voice. He made Frodo sound like an Orc with a hangover, but he did make us laugh.”

Monaghan got the good news on his cell phone, riding home in a van with several other actors. They all fell silent, chewing on their own jealousy. Monaghan spent the rest of the ride with one arm around his then-girlfriend, feeling euphoric and uncomfortable.

Monaghan learned to surf in New Zealand. But his ultimate wave came this past New Year’s Eve, when he went surfing with fellow hobbit Billy Boyd. After catching a big one, he shot to the top, only to realize the water behind him was about to collapse on him. “For about three seconds,” he says, “I was surrounded by cascading silent walls of water — then I shook the spray from my face and emerged on the other side, ten feet taller.”

Boyd saw the whole thing happen but doesn’t want to give Monaghan too much credit. “His surfing’s all style and no substance,” he says. “I’m a better surfer, by about a million.” He laughs. “Make sure you print that — it’ll piss him off.”

The Rings cast members pledged they would keep getting together annually. That hasn’t happened, but Boyd and Monaghan have remained close. Boyd reports, “Dom’s really good about letting you stay at his house, but when you’re trying to watch a movie, he does insist on walking around the house in the nude and making cereal.”

After the last Rings movie wrapped, Monaghan found himself at loose ends. He had just been on an epic quest to the other end of the world, and now he couldn’t go home. He tried anyway. “You’ve changed,” a Manchester friend said accusingly. Monaghan thought, “Of course I’ve changed. I’ve done more in the last two and a half years of my life than ever before. If I hadn’t changed, I’d have to kick myself in the ass.”

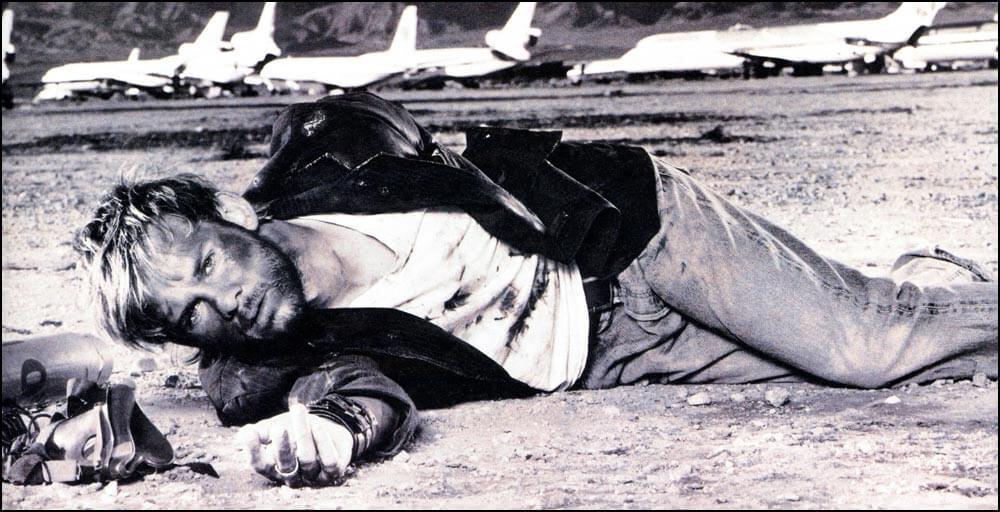

Not knowing where else to go, Monaghan moved to Los Angeles. He says quietly, “I never wanted to come to L.A. and feel backed into a corner, but that’s exactly what happened.” Monaghan would stay up until 5 a.m., drinking too much, playing video games and writing in his diary. Then he’d sleep until 4 p.m. and have the same day all over again, totally alone.

“I didn’t have a car,” he says, “I didn’t have a phone — but I didn’t have any friends in L.A. anyway, no one that I could call up. I wasn’t going out, I wasn’t trying to get back on track. I was just spending a year doing nothing. It was unhealthy and melancholy for no real reason — and it was cumulative, because I got pissed off that I was depressed.”

When The Fellowship of the Ring started having premieres around the world in 2001, Monaghan was reunited with his castmates, all of whom had enjoyed more success than he did: “I was filled with shame and in this paradox state of clearly needing help but denying it when people offered.”

He visited Mexico, where Boyd was filming Master and Commander. Boyd said he couldn’t get him a job but advised him to do something that made him happy. “So he surfed a lot,” Boyd says. “Being able to get in the water really helped him.”

One morning, Monaghan woke up to find his depression had abated. He started answering the phone and eating better. “I just snapped out of it,” he says, shaking his head at this small miracle inside his skull.

After J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof wrote the pilot for Lost, they had just twelve weeks to cast the show’s fourteen lead roles (and one dog). There was no part for Monaghan — Charlie was meant to be a faded pop star in his forties, someone of George Michael’s ilk. But Abrams and Monaghan met and hit it off. The part was turned into a younger musician, a one-hit wonder. Monaghan soon showed that he could play a grungy, unreliable guy — but with a twinkle. He soon proved so popular that the show’s producers made an unusual public pledge that Charlie would never be killed. Halfway through the season, Charlie has already endured the plane crash, a cave-in, a near-death from hanging and a surprisingly quick withdrawal from heroin. “It’s a Disney show,” Monaghan says with a shrug.

Monaghan knows the events in store for Charlie this season — he wanted to make sure he could modulate his characterization properly — but the cast is kept in the dark about the show’s big mysteries. “It would be interesting for us to have dinner with a bunch of fans,” he says. “They’d realize we talk about the same sh* they do: Who’s going to die next? What do you think the monster is? When are we going to cook the dog?”

The show’s ensemble seems cheerful and has good camaraderie. Monaghan enjoys the fake voicemails he trades with Abrams: “I call up as his Indian chiropractor, he’ll call me as a DJ from Orange County and I’ll call him back as a German professor wanting to get his waist measurements. I think that’s going to continue for years.”

After lunch, Monaghan heads for the makeup trailer. The marks on his skin tell a history. Tattooed on his right shoulder is the elvish symbol for nine, a mark famously shared by the principal actors of the Lord of the Rings movies. On his left shoulder is a quote from the Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever: “Living is easy with eyes closed.”

The Beatles are a huge influence on Monaghan: When he fled from McCartney, it was because the idea of talking to him was overwhelming. He’s always loved being part of an artistic gang, and it’s no accident that in his twin career peaks, Lord and Lost, he’s part of a much larger ensemble. The second half of that lyric is “misunderstanding all you see,” which explains how Monaghan chose the tattoo: as a caution to himself. He wants to keep his eyes open, be receptive to the world and ask himself, “What would Lennon do?”

Monaghan has one other tattoo, on his right foot. It’s two small stars, one black, one white; he got them after his first year in L.A., when nothing was going right. “I wanted something that would inspire me to get freer, to get lighter,” he says. “I came to understand that the black star was where I was at, and the white star was where I wanted to be.”

Last year, when he was visiting New York, a woman wearing stiletto heels stepped on his foot. She apologized and left him bleeding. When his skin healed, there was a nick in the black-star tattoo. Friends told him to get it touched up, but Monaghan knew he shouldn’t: Some of his darkness had vanished.