With all Cate Blanchett has on her plate—three young boys, a three-stage theater, and a global acting career—she might be forgiven the occasional emotional outburst or diva-like moment. Instead, the author encounters a Hollywood anomaly: a star who doesn’t do drama offscreen, whose only hint of domestic conflict is her husband’s threat to divorce her if she gets cosmetic surgery, and whose latest role, as Brad Pitt’s soulmate in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, has her focused on aging and death.

When David Fincher first saw Cate Blanchett play the Virgin Queen, a decade ago, he was stunned. “I remember coming out of Elizabeth and thinking, Who is this?!” the director says. “I didn’t know who she was, but that power from someone in relative obscurity was like seeing her leaping fully realized from the head of Zeus.”

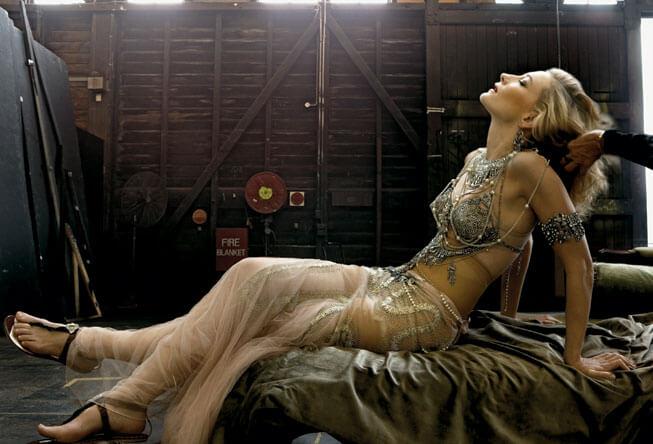

She’s so slender you’d never guess she had a baby last spring, so calm and unhurried you might think she had nothing else to do but sit around having tea at the Hotel Bel-Air. Intelligent and well mannered, she answers questions obligingly and shows photographs of her three small children on request.

But the portrait of Blanchett that emerges from several hours of conversation seems to be sketched in invisible ink; it starts to fade as soon as she’s gone, and it quickly disappears from view. As compelling as she is on-screen, in real life she can be restrained and self-effacing.

Most striking of all is an absence of the intense laser-focused charm that stars and politicians turn on and off as if flipping a switch; Blanchett seems to lack their reflexive need to make everyone love them. As an actress, her elastic face provides a blank canvas for a dazzling range of transformations that are facilitated by the egoless state she strives to achieve in the name of “fluidity.” In person, she is willing to sit and answer questions; she is cordial and cooperative; but you have the feeling she might actually be thinking about the weather, and perhaps she’d just as soon be folding laundry.

“She’s just so smart, capable, facile, thoughtful, beautiful, and emotionally present,” Fincher says. “She helps you as a director in so many different ways, coming up with ideas you may not have thought of. She’s going to come having done her homework; she’s done all the thinking, and it’s deep and measured. She has a great work ethic, knowing her lines and knowing everyone else’s lines. She prides herself on making things work. She’ll say, ‘Well, I see you’ve given me eight words here, so how about this?’ She’s not one of those people who says, ‘I need a soliloquy—someone’s going to have to come in and retool this.’ She’s the prototype of what you would want to have.”

She was drawn to Benjamin Button by the very elements that have caused studio executives to agonize about the open question of its commercial appeal. “David said, ‘This film is about death,’ and I think it’s great,” she says. “We’ve enshrined the purity, sanctity, value, and importance of bringing children into the world, yet we don’t discuss death. There used to be an enshrined period where mourning was a necessary part of going through the process of grieving; death wasn’t considered morbid or antisocial. But that’s totally gone. Now we’re all terrified of aging, terrified of death. This film deals with death as a release. I hope it’s a moment of catharsis.”

“It’s sort of like a repository for your grief, about whatever you grieve about—the loss of loved ones, the missing of opportunities, whatever,” Fincher adds. “You hope it will leave people feeling hopeful about certain things, and sad about certain things.”

The opposing narrative arcs of the story, in which Benjamin gets “younger” every year while his true love ages from 6 to 86, force the couple into an ever changing succession of relationships with each other that encompass every life stage from birth to death. “If you age with somebody, you go through so many roles—you’re lovers, friends, enemies, colleagues, strangers; you’re brother and sister,” Blanchett observes. “That’s what intimacy is, if you’re with your soulmate. Marriage is a risk; I think it’s a great and glorious risk, as long as you embark on the adventure in the same spirit.”

The intersection of marriage and death is a poignant subject for Blanchett. Her father, a Texas-born advertising executive, married an Australian teacher and settled in Melbourne, but he had his first heart attack at 32 and died at 40, leaving his 39-year-old widow to raise their three children on her own. “It’s hard to compute something so massive. I just sort of rolled with it. You sort of see it from other people’s perspective. I could see that my sister was so young, and I felt it was tragic that she might not remember him. I could see how it affected my brother, who was 11 or 12. I saw what a struggle it was for my mother. I think about my father and how sad it was that he never had grandchildren.”

But she utters not a word about her own grief. “Maybe this is just me trying to live with the loss,” she says, her tone affectless.

That loss left her with an enduring sense that “the presence of death can coexist in life. I just don’t take things for granted. I know that time is very short.”

She does not have the consolation of believing in an afterlife: “I wish I did; it would be really comforting. But I don’t think we’re that important.”

As a child, Blanchett discovered the pleasures of playacting long before her father died, but she never intended to make it her career. “Acting was fun, but I don’t think it crossed my mind that I could do it,” she says. “I thought the most important thing was security, because of my mother; it was insecure bringing up three children by herself. I thought, I want to do something more practical, so I decided to study economics and fine arts.”

But she found she couldn’t get away from acting, and after a brief stint at the University of Melbourne and time off for traveling, she ended up studying in Sydney at the National Institute of Dramatic Art. “It was inescapable,” she says. “I loved the looseness and freedom. Some ideas, like what you’re going to do with your life, take time to form. When something is a vocation, you don’t really make a decision about it.”

She describes her commitment to Upton as a similarly irresistible force. They got to know each other in 1996 while working on the Australian film Thank God He Met Lizzie, but it was hardly love at first sight: “It was kind of animosity at first,” Blanchett says.

And yet when they finally got involved, Upton asked her to marry him within a few weeks. Why did she say yes? “I couldn’t not,” she says. “We were in exactly the same place at exactly the same time. He turned to me after a few days and said, ‘Cate…,’ and I thought, Oh, he’s going to ask me to marry him—and I’m going to have to say yes! He didn’t, in fact; he asked me what I wanted for dinner or something like that. But I’d never had that thought before. I thought, This is extraordinary! I’ve never felt this before. What an adventure! It was a leap, but I wasn’t leaping by myself. It was a leap into the future.”

That leap was motivated in part by Blanchett’s astonishment at finding someone who could share her creative life. “I don’t think I had ever discussed work with anybody until I met him,” she says. “He’s a really constructive critic. I think he’s a truly independent thinker.”

As for Upton, he says simply, “We sort of clicked. With other people, maybe they don’t get you. But with someone who does, you go, ‘Ooh—I’m got! Someone’s got me!’ It’s a relief and a pleasure.”

Their life together is dauntingly full. Even as Blanchett ricocheted around the world making films, she managed to have two sons—seven-year-old Dashiell and Roman, who is four. And last April she delivered her third child, Ignatius, whose nickname is Iggy and whose brothers call him Piglet. “We don’t mind a bit of chaos,” she says. “As your life becomes more populated with little people, you have to adapt, but I’ve never been frightened of change.”

“As a married couple, we’re kind of used to coordinating with each other. It’s been very interesting; she’s an interesting person to be in close proximity to. But she doesn’t overcomplicate things. She has a very strong, simple process; she breaks things down and asks the right questions. That’s a great thing to be around.”

As Blanchett approaches her 40th birthday, next May, aging is likely to provide yet another challenge, but she claims not to worry about its impact. “I don’t think about it a lot,” she says. Nor does she acknowledge much interest in Hollywood’s obsession with fighting time; although many actresses love to dish about cosmetic surgery and who’s doing what, Blanchett seems bored by the whole subject.

“I haven’t done anything, but who knows,” she says. “Andrew said he’d divorce me if I did anything. When you’ve had children, your body changes; there’s history to it. I like the evolution of that history; I’m fortunate to be with somebody who likes the evolution of that history. I think it’s important to not eradicate it. I look at someone’s face and I see the work before I see the person. I personally don’t think people look better when they do it; they just look different. You’re certainly not staving off the inevitable. And if you’re doing it out of fear, that fear’s still going to be seen through your eyes. The windows to your soul, they say.”

Blanchett is clearly a believer in the importance of rigorous self-discipline, both in maintaining a career and in keeping a level head about it. “Someone might have a germ of talent, but 90 percent of it is discipline and how you practice it, what you do with it,” she says. “Instinct won’t carry you through the entire journey. It’s what you do in the moments between inspiration.”

In any case, practicing her craft is only part of the picture for Blanchett, who has always maintained a careful distance from Hollywood. “I don’t exist in that world,” she says. “I observe it, but there’s so much else to be thinking about. Maybe it’s because I’m with someone who’s not with me because of that; I’m not a trophy. He likes the vessel, but he also wants to make sure the vessel is full. The world of film can be so noisy, but the other aspects of my life are actually the noisiest parts of my life. My best friends are a social worker and a visual artist.”

“I want to be in a dialogue, not a monologue.” She snorts derisively. “Says she, talking for two hours to Vanity Fair.” And then, her ego firmly in check, she exits, stage left, leaving not even a whiff of attitude behind.