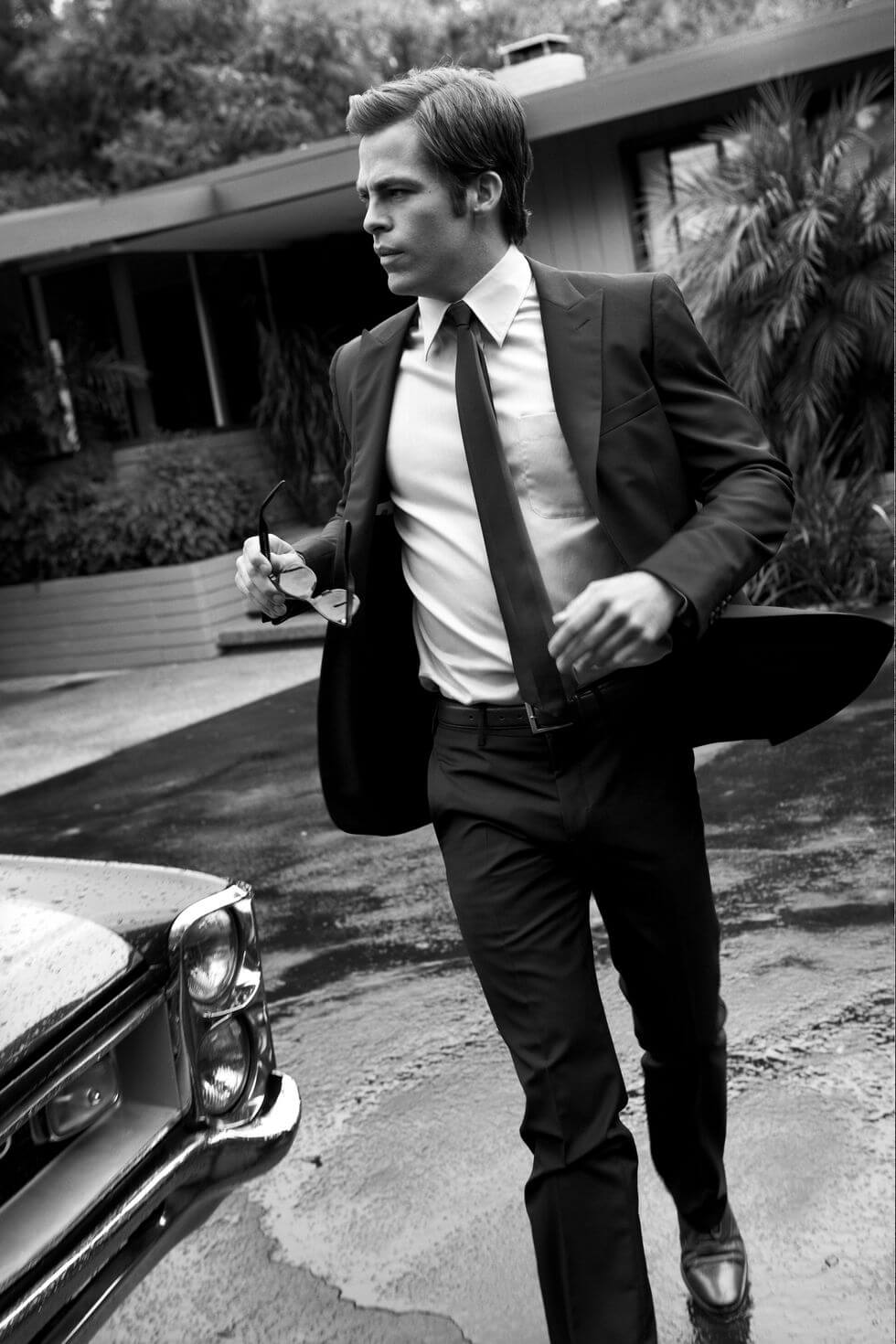

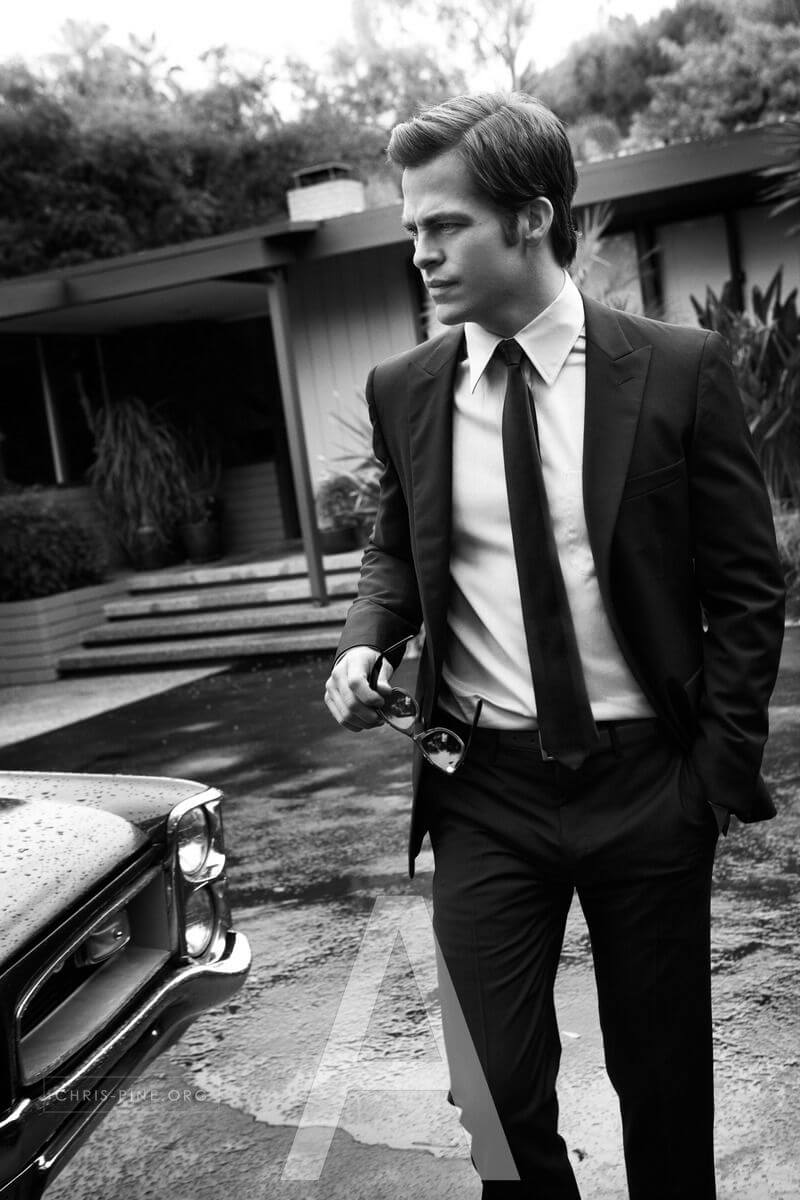

You’re a talented man on the rise.

Intelligent, deeply committed to your craft. You devote serious hours and effort to some lofty goal or project or, say, movie role opposite a then-starlet named Lindsay Lohan. The universe responds with a collective “Meh.” Chris Pine has been there. He’s endured so much rejection and outright dismissal over the years that it’s hard to know what has shaped him more–the jobs scored or the knocks along the way. On the bumpy road to where he is now—a 32-year-old action star headlining two of Hollywood’s biggest franchises, Star Trek and Jack Ryan—he could have quit many times. Perhaps when, as an English lord opposite Anne Hathaway in The Princess Diaries 2, he was described by one critic as “a terra-cotta Chia Pet doing a Robert Wagner impression.”

With his looks Pine could have easily played second- or third-rate Romeos for the rest of his career, making good cash. “When I saw how much I was earning for The Princess Diaries 2, it was more money than I’d ever seen in my life. That can mess with you. You never want to buy into money equaling self-worth or happiness.”

And then he was offered two big jobs. Two different jobs. One is suited to his talents and ambitions; it was his vision of himself. The other would make him gobs of money.

How can a man choose between two different versions of success? The two elements you most desire, split down different paths.

Chris Pine had a week to decide between the two jobs. And the 28-year-old actor agonized, because, well, the pinnacle of his career to that point had been The Princess Diaries 2. But now two movie studios wanted him. He could take a role as a disgusting, chemically imbalanced detective in the kind of gritty, actor-driven gig he’d dreamed of. Or he could play James T. Kirk in a Star Trek prequel.

“I think the most dangerous word in the English language is should. I should have done this. Or I should do that. Should implies responsibility. It connotes demand. Which is just not the case. Life ebbs and flows.” So when the two jobs were offered, he talked it over with everyone he could, and spent a lot of time by himself, wondering what he should do.

With the early roles, even the maligned ones, “I just felt really lucky. For a while, I’d been planning to move to New York to do theater, but suddenly I booked two or three jobs. I kept telling myself, ‘This is good.'” Pine says he learned to be driven by a narrative that comes from within. You have two choices when you’re met with negative voices: “You either listen to the naysayers and fall into the pit of self-loathing, or you stay on your path and move forward.”

Pine was flying on fear during his audition for Star Trek. But his tryout went “as badly as you can imagine,” though perhaps not as badly as the one to play Jake Sully in Avatar, a role he lost to Sam Worthington.

The Trek read was full of talk about stardates and decloaking, and Pine just assumed he’d never win the part. “You realize your failures weren’t even failures. You just weren’t as good as you thought you’d be.” That gives him the strength to try again — knowing that even if he thinks he’s failing, he’s probably not. But he received a callback and nailed the second reading. “When you want something enough, it brings out primal emotions. You get into this place of ‘must happen, must happen.'”

Chris Pine’s ex-girlfriend used to wake up every morning at 7 a. m. and is, as he tells it, the very definition of sunshine. She is ready. Yesterday’s gone; today is better. “I’m so envious of that genetic wiring that immediately puts a smile on your face. My genetic wiring just puts creases in my eyebrows.”

Pine has been focused on changing. It starts by taking cues from others, he says. He follows his girlfriend’s lead, and studies how George Clooney makes fun of himself. And through this, Pine has learned to refocus. “The only thing you sometimes have control over is perspective. You don’t have control over your situation. But you have a choice about how you view it.”

Damn, he really wanted that gig as the strung-out detective. It was so right for him. It was everything he’d prepared for. He was freaking out. But then Pine’s sister said to him, “Instead of looking at Star Trek as a sacrifice of your artistic principles, is there any way to look at it as a larger challenge?” And he thought about that and realized she was right. The strung-out detective role was easy. He wanted to play it because he felt prepared for it. Star Trek was hard. How do you play a James T. Kirk that William Shatner already dominated? Pine didn’t know.

So he took the job. He might not have taken it if it had been offered years ago. He’d have been too nervous.

That’s the change in perspective we’re talking about. Look at things differently, and downsides become opportunities. The best parts of life aren’t polar opposites. A choice is just two different ways to make the most of opportunities. It’s a good problem to have, once you’re not afraid of looking back. Which, in this case, Pine no longer is.

“When I started Trek, I looked at it, and then I was climbing it, and I didn’t have time for anything else but climbing the thing and getting to the top. And that’s an incredible space to exist in, because there’s tremendous responsibility. There’s tremendous pressure. But all those just clarify your vision.”

It says something about Pine’s individualism that his favorite quote, which he launches into by memory and without hesitation, is from Theodore Roosevelt: “It is not the critic who counts. Not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles. . . The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.”

Growing up in the San Fernando Valley, Pine loved baseball, and he was good at it. “I was always that kid who was younger than everyone on the team but asked to pop up to the next level.” Then one season, that stopped. “You’re smaller than everyone else and you’re striking out.”

It was a moment that set Pine on the course that would make him famous. Acting came naturally, and that pushed him to challenge himself constantly. “Mediocrity scares me. It’s the fear of not being as good as you want to be. If you give over to that fear, it will sabotage you. As much as I can, I try to use that fear to guide me.”

This time around, in Star Trek into Darkness, Pine says there’s “much more action; much, much more intensity; and a lot more fighting. Seriously epic.” As Abrams explains, “Chris was always game, always enthusiastic, and always tireless to keep making the movie better. Chris takes his job seriously, but he’s willing to look like a fool. It’s what makes him infinitely cooler than every wannabe out there.”

To stay sharp now that he’s graduated from the audition mill, Pine continues to act onstage. “It’s humbling to do theater. It grounds you. 2011, during a self-imposed hiatus after a string of movies, he won a Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle award for The Lieutenant of Inishmore.

“I like the rhythm of being onstage.” It was the day-in-day-out approach he saw with his dad as an actor. “Acting was work for him. It was a job. I always thought there was something great about that. Almost like you’re working in a bank. You don’t get carried away with yourself.” Plus, onstage, there’s no safety net—he’s embracing fear.

And, of course, by periodically pulling back from blockbuster projects, Pine has more fuel to slay future giants. And no movie is bigger for him than Jack Ryan. The film has firmly established him as one of Hollywood’s leading men: Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck, and Alec Baldwin have all played the CIA analyst. The latest version, directed by stage and screen veteran Kenneth Branagh, is an origin story. Pine stars as young Ryan, an injured Marine who’s recruited by a CIA lifer to work in intelligence.

The movie challenged Pine. It was shot in London, Moscow, and New York. Pine had to do major fight scenes and rode a Ducati “without a helmet, going through potholes on the FDR Drive in New York City, scared absolutely s**less.” To overcome any apprehension about filling such big shoes, Pine turned to Baldwin, with whom he worked on Rise of the Guardians. “I was transparent in my desire to be mentored. ‘Please give me sage wisdom,’ I’d say. Alec just took me by the shoulders and said, ‘Do it,’ which to me meant ‘Jump in, dive in, take it. Smile and laugh.'”

What Pine learned from the original captain of the USS Enterprise, William Shatner, also helped. “Bill squeezes every ounce of joy out of life. He never takes himself too seriously. He’s transformed his career by making fun of himself, and he’s unstoppably creative.”

Mostly, though, Pine wants to appreciate whatever’s next. “Life flies by and it’s easy to get lost in the blur,” he says, echoing Ferris Bueller. “In adolescence, it’s ‘How do I fit in?’ In your 20s, ‘What do I want to do?’ Your 30s, ‘Is this what I’m meant to do?’ I think the trick is living the questions. Not worrying so much about what’s ahead but rather sitting in the gray area; being okay with where you are. If you can find the parity between ‘Where am I going?’ and ‘What’s my purpose?’ you’ve got two pretty solid pillars for your coffee table.”