The final film of the Tolkien trilogy marks the end of a saga that shaped Elijah Wood and Sean Astin.

ELIJAH WOOD began his career modeling boys’ clothing in a mall. He was just 7 when his mother moved him from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to Los Angeles in 1988, and his screen debut came almost immediately, with a small part in the second episode of Back to the Future. Enough decent roles kept coming his way that he did not have time to do a single stage play or complete high school. He figured he could learn more “from life,” anyway, and by working with the likes of Peter Jackson, the rumpled New Zealand director who had never grossed more than $3.1 million with a film in America before he began negotiating a deal to make three, for $300 million, based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s cult classic novels — arguably the greatest gamble in filmmaking history.

Jackson offered Wood the part of Frodo Baggins. Wood was a natural for the role not only because of his size — a slight 5 feet 6 — but because of his enormous blue eyes, which make him seem the epitome of wide-eyed innocence while also projecting sadness, terror or depth. When the 18-year-old actor took off for New Zealand in summer 1999, it was only the second time he had been away from home on his own.

Wood recalls that it was a clear day that Aug. 30 when his plane landed in Wellington and a producers’ assistant drove him around its spectacular bay. He was unnerved, though, as he often is when starting a film. “There’s the sense of ‘I’m not familiar with any of these people, I’m in a foreign land, I’m by myself.'”

But they took him to a cast dinner that first night where Fran Walsh plunked him next to Sean Astin. “She was like, ‘We’ll make sure Elijah sits right next to you,'” recalls Astin, who was a decade older, 28 then, and married with a child. “‘I don’t want him to feel scared.'”

It worked — Wood says he felt “immediately comfortable” and remained so their nearly 16 months in New Zealand, with Astin becoming “like a brother.” Astin, however, was not so relaxed. The one who was supposed to do the soothing found himself on edge those many months, for a reason hard to imagine now — money.

Like Wood, Astin had been a child actor, though he didn’t have to gravitate to L.A. — he was the son of actress Patty Duke. But his own roles in films such as Goonies and Rudy enabled him to buy a house in the flats of Sherman Oaks and then — closing escrow the day he got his Rings part — a fancier place in the hills of Encino.

Wood lived with his family in the Oakwood Apartments by Universal Studios, then in a house in the Valley and then — also right before Rings — got a pad befitting a budding star, in Santa Monica. The difference was that Wood’s family used his new place while he was off in the wilderness, while Astin brought his wife, Christine, and toddler, Alexandra.

“I made a strategic mistake,” Astin says. “Instead of leasing that house out and going to New Zealand and coming back with the money that I made, [it] went to sustain the house. It was like a $5,000-a-month kennel for the Siberian husky.”

His nervousness peaked right as The Fellowship of the Ring, was opening two Decembers ago. While he was doing press at the Waldorf hotel, his wife told him she was pregnant again. “I thought I was going to collapse. My head was going to explode.”

Then the first Rings film took in nearly $1 billion worldwide and a year later so did the second, The Two Towers.

The third installment, The Return of the King, comes out next month, when Jackson will get to show us why it’s his favorite of the trio, with the story’s “triumphant” resolution on both the macro and micro levels: the final battle and the emotional drama coming from Frodo and Sam.

A Look Back

Jackson’s Los Angeles lawyer, Peter Nelson, recently visited the director in Wellington and they went through the “what’s happened in your life?” exercise. For them, that meant looking back to November 1995, when Jackson began to pursue his dream of making a movie based on The Hobbit. The problem was, “the rights were disjointed,” his lawyer recalled, but Miramax Films did have rights to The Lord of the Rings. So these films were a “historical accident,” Nelson quips now.

Producer Mark Ordesky risked being shown the door after helping convince New Line Cinema to take over the project from Miramax and wound up as the studio’s chief operating officer. Orlando Bloom was barely out of drama school in London when Jackson picked him to play Legolas and now is primed to star as a knight in Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven, which that director says will be “slightly larger” than his Gladiator.

Jackson’s gone from low-budget indie movie-making to setting new Hollywood pay scales for directors with the $20 million plus 20% of the gross he is getting next for his remake of King Kong. For Jackson, the films were an homage to the English heritage of his folks, who moved after World War II to New Zealand.

“The experience in making these movies has been very much that of the characters we embodied,” says Elijah Wood. “Going on this journey with a fellowship of people and returning home having grown and changed.” In his case that meant “being so immersed in my life in New Zealand, and in Middle-earth that I didn’t know what my life meant anymore, which is kind of similar to what Frodo goes through and, I think, what a lot of the characters go through. They go home and it doesn’t mean the same.”

Switching Coasts

When Wood got back from New Zealand, he went into “hibernation” in Santa Monica, not even telling some friends he was back. His mom said that went on for months. “I didn’t quite know what my own life meant free of a film. Suddenly it was up to me to dictate these things.”

He switched coasts after making a movie in Manhattan last winter with Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. The night a blizzard blanketed the streets he walked 40 blocks in “utter peace,” then a few months ago bought an apartment in the Flatiron District — his first place that’s truly his own. He does not have a car, preferring to join the crowds on the subway, a book bag over his shoulder.

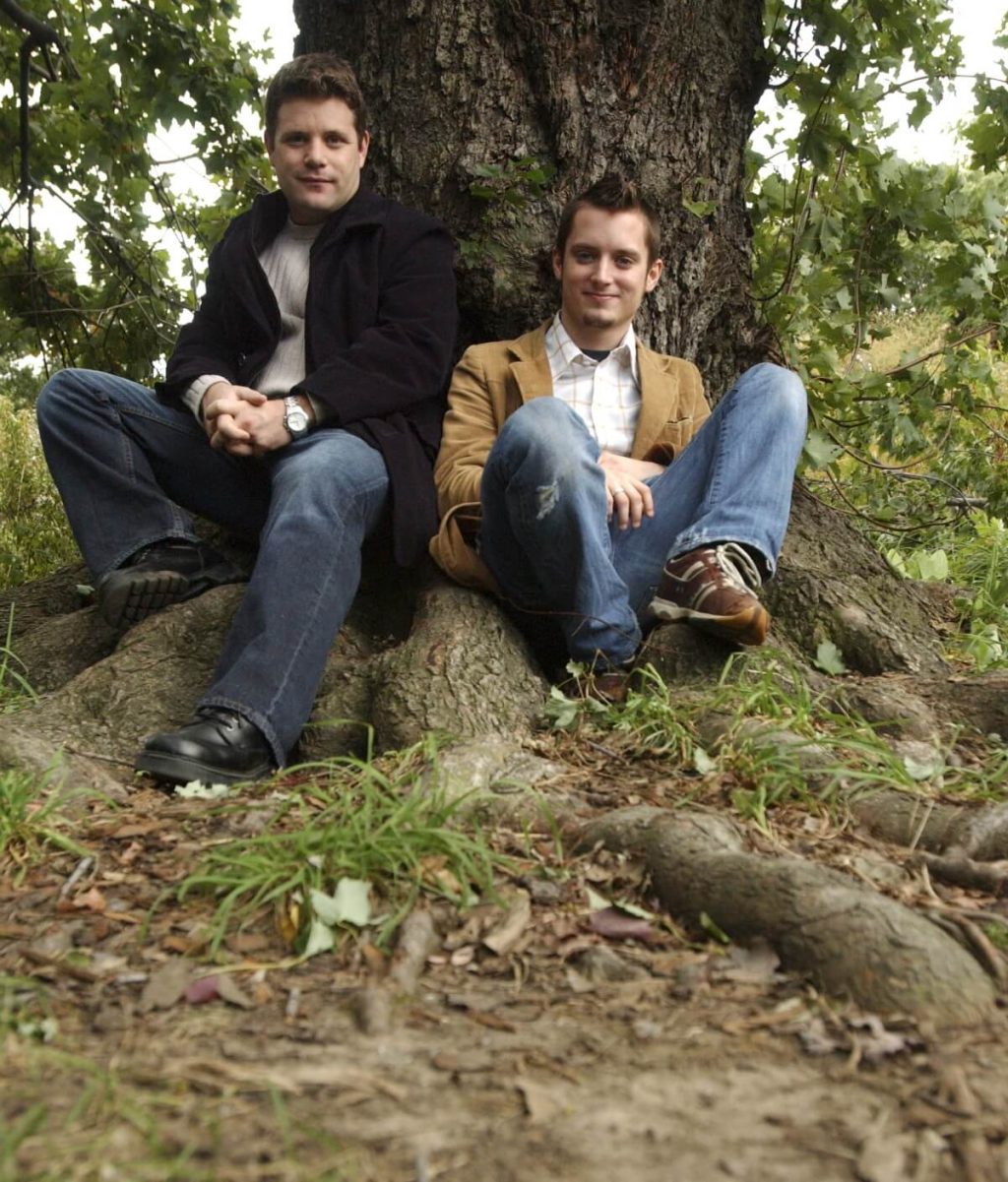

Last year, they went together — and stood in line — to attend Star Wars: Episode 2 Attack of the Clones. Wood was part of a delegation of Rings actors who visited the sets in Australia where George Lucas was making his latest series, back when the Rings crew felt “like a bit of a rogue group” in the shadow of that sci-fi franchise. Their status had changed by the time Astin ran into Lucas and his kids at a recent MTV awards show. “His daughters were like, ‘I love the hobbits!'” Astin reports when he meets us off Central Park, our staging point for a rowboat ride in its lake.

Wood can’t escape the recognition game despite looking more like a bohemian English schoolboy than a Shire creature with his torn jeans, tan jacket, wispy goatee and hair fluffed into a mini-Mohawk. “To your right,” he whispers as Astin rows us into the lake — there’s a photographer on a bridge who he suspects is after more than fall scenery.

Wood got a taste of tabloid realities when he was linked briefly to actress Franka Potente — the “rumors” had his mother calling to ask if they’d secretly married. That’s “ex-girlfriend” history, Wood reports in the boat, but his right hand still bears a ring the German beauty gave him, inscribed in Hebrew with the words of Hillel, the 1st century rabbi, “If not now, when?”

“I just love the sentiment,” Wood says, and then lights a clove cigarette, which reminds him how Astin’s little daughter would plead in New Zealand, “Elijah, don’t smoke.”

Astin measures his Rings years through the development of the precocious Allie. She was 2 when they arrived in New Zealand and soon was taking in everything, like how they swerved to the other side of the street to avoid a rowdy group exiting a bar. After that it was, “No alcohol, Daddy! I don’t ever want you to have alcohol.”

Looking back is at the heart of their key scene in The Return of the King. Wood recited his lines for it at three stages: In L.A., when he was a hopeful making his audition tape for Jackson; then in full costume, on the side of Mt. Ruapehu, a real volcano in New Zealand; and finally this past September, during a looping session in London.

Though a saga like this is fantastical by definition, Jackson’s mantra was “make it feel real,” as in the scenes on the mountain which he calls “the heart” of the film. “If anybody is going to cry,” the director says, “that’s going to be the scene that will start them.”

By phone from New Zealand, Jackson says he cried himself late one afternoon in May 2000, when they filmed Wood collapsed on the side of Mt. Doom when he can’t go on, “nor can he give the ring that he’s carrying around his neck to Sam because Sam would not destroy it. He knows how powerful this thing is.”

In New York, Wood recalls how Astin’s Sam “cradles Frodo and tries to make Frodo remember the Shire. ‘At this time of year, the strawberries would be in bloom….'” Jackson’s favorite line from the films is Sam’s declaring, “I can’t carry it for you, Mr. Frodo, but I can carry you,” and hoisting the exhausted hobbit on his shoulder.

Science fiction writer Chris Claremont (X-Men) views Jackson’s as a rare “intimate epic,” in which the spectacle is mere “eye candy.”. What makes the audience care is: Will Frodo find the strength to destroy the ring? Will Aragorn fulfill his destiny to be king? What’s going to happen to Sam, the sidekick? “What makes the films so riveting,” Claremont says, “is you’re locked in on the fate of these small and human characters, and these characters are literally small, real and fallible people up against impossible odds.”

Roles Lined Up

Our rowboat finishes circling the lake. Then we head off for photos in the north end of the park, where the woods, waterfall and stream will have to pass for New Zealand. Wood and Astin are nimble and willing, whether climbing on a tree or a boulder. Having spent most of their lives in front of cameras, they check the results on a photographer’s digital screen — old pros at 22 and 32.

They understand that the biggest “bounce” off a movie like this goes to the glamorous actors who have the more classically heroic roles, like Bloom, or rugged Viggo Mortensen. Neither seems to mind.

Whatever these movies do for Astin, his return, at journey’s end, to the home of the hobbits is sure to be his enduring memory of the Rings years. Jackson needed a little girl to play Sam’s daughter, a child comfortable enough to run to the man and be hoisted in his arms. Who could do that better than Alexandra Louise “Allie” Astin?

Wood has his next role lined up, as a student journalist among London’s hooligan soccer fans. Then he may play the son of a circus strongman. But while his face will let him play young a while longer, his quest is for “roles that are older.”

In the van back from the park, he goes over photos taken of him in a tapered Prada suit that makes his shoulders look broad. His jawline is firm and clean shaven, his hair brushed back. “That’s also part of what my journey has been about. I mean, I started when I was 8, so part of my journey has been about growing up within the industry and growing into an adult actor, being recognized as a man and not a boy anymore.”

Astin examines the photos and says, “Stunning, dude.”