Hobbits are cute.

And short.

And filled with joy.

And they’re currently charging into Los Angeles’s Woo Lae Oak, a Korean restaurant that they frequent when they’re in town, looking wide-eyed and excited.

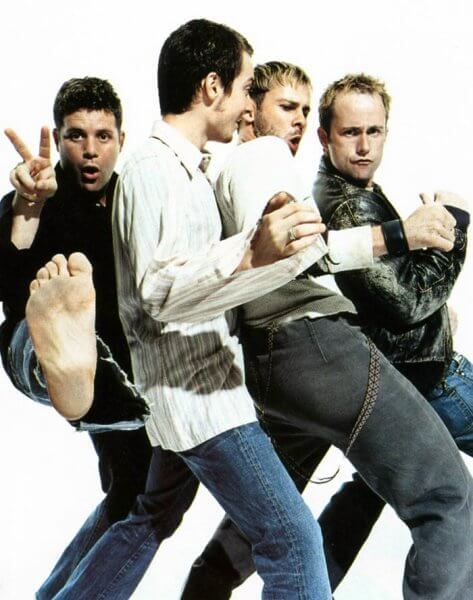

Playfully jostling one another, Elijah Wood, Dominic Monaghan, and Billy Boyd enthusiastically descend upon a large booth that nearly envelops them. Sean Astin, soon joins us to chow down on strips of meat, shrimp, scallops, and mushrooms. “Hmmm, hobbits like mushrooms,” Astin says sweetly, with an English-inflected accent, channeling his character, Samwise Gamgee.

When Wood excuses himself from the table, Monaghan cocks his head and seizes the moment. “All right. While Elijah’s away . . .”

“He cried a lot,” Astin confides, speaking of Wood’s experience spending 15 months shooting the Lord of the Rings trilogy in New Zealand.

“He was always crying,” Astin continues as Boyd shakes his head, looking grim. “We were always consoling him.”

“He missed his mom. He missed L.A.,” agrees Monaghan. “He had a blanket that he forgot.”

Astin adds, “He would say, ‘I don’t think I can make it, you know, I . . .’ ”

“‘. . . need you guys, I need you,’” Monaghan completes the sentence with a frown.

Bear in mind the British expression, “to take the piss,” meaning to make fun of someone in a playful, ironic way. It’ll take you a long way to understanding what it’s like to be in a room with these guys.

The Lord of the Rings has many faces: Legolas, played by Orlando Bloom; Viggo Mortensen’s hardened ranger, Aragorn; Miranda Otto, and Cate Blanchett; and the lovable genius behind it all—New Zealand director Peter Jackson. But it’s the hobbits—these four leading lads who make up the heart of this grand epic. Their friendship has become part of pop-culture lore. There have been countless stories telling how they would go surfing together, how they all got the same elvish tattoo, went bungee-jumping, and DJed at clubs in Wellington.

“The power of the bonds that we’ve all talked about to so many different reporters is unimpeachable,” Astin says. “Most interviews don’t focus on the complexity of the relationships. And so we always fell back on something that’s true: That it was an unbelievable experience; it was the most meaningful, the most powerful, the most close that you could ever imagine.”

The Lord of the Rings has been wondrously stretching the limits of imagination ever since J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy world of men, elves, and dwarves fighting an epic battle between good and evil hit bookstores in the mid-fifties.

“The film has been life-changing for people who watch it, thinking, ‘Wow, this film’s incredible—I’ve never seen anything like it,’” Monaghan says. “But it was also a huge turning point in all of our lives. It’s profound what we all went through.”

The foursome suspects that the genesis of their intense friendship—they were asked to come to New Zealand before the rest of the principal cast—was no accident. “We had become great friends within the first two months of preproduction. It was an absolute blessing that we were given that kind of time,” Wood says. “’Cause not only did it give us the chance to figure out the material and understand the process of the film, but it gave us the opportunity to form the relationships that were necessary to fulfill those roles.

“Pete related to hobbits the most. We embodied not only what he loved most about the film but I think what he loves most about life—that kind of carefree nature; the positivity, affection, friendship, and warmth. When we came on the set, he was at his happiest.”

“They can look at these guys and feel the reality of the film,” Bloom says. “The hobbits are the audience’s emotional vehicle—they’re the heart and soul of this film.”

And it’s coming to a close—the third and final film, The Return of the King, is due in theaters on December 17. What’s to become of these actors who’ve been so deeply moved by the experience? Usually, when a set breaks, the relationships also unravel, and everyone moves on.

PREMIERE: Dom, weren’t you telling me that there was a real boys club during the making of the movie?

Monaghan: Yeah, how there were no women there.

Wood: Well, Cate Blanchett came over.

Boyd: And Orlando, who’s quite feminine, was there.

Monaghan: He would tidy up for us.

Boyd: We had parties…

Monaghan: And he would have to clean up afterwards. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be invited to the party.

About this “taking the piss”—it’s rooted in the cross-the-pond humor of the two Brits, Monaghan and Boyd. “In America, it’s about making people feel good. You know, it’s like, ‘Hey, good job, man, good job.’ Whereas in England, it’s ‘You’re a d*ck,’ ” Monaghan says. “I think when Elijah and Sean first turned up in New Zealand, they didn’t really know what was going on with us, because all Billy and I did as soon as we met each other was just taking the piss out of each other. Elijah used to get a little bit freaked out. He was like, ‘I don’t know if these guys like me.’ ”

On set, tough love and roughhousing became a staple of behavior, with the hobbits constantly sneaking up on one another, laying punches in the kidney or slaps to the head. Joining them in the fray were Mortensen, Bloom, and many of the other cast and crew. But not everyone. Blanchett, who was only on set for three weeks, escaped getting too sullied. “I was the queen of the elves: They were terrified.”

During dinner, the four are constantly finishing each other’s sentences, riffing off one another, listening respectfully when one is making a serious point, and teasing someone when the point gets too serious. In separate interviews with each hobbit, they’re constantly getting calls from one or the other (or from Bloom, who dubs himself “an honorary hobbit”).

Referring to the four actors as “the hobbits” comes quite naturally to a journalist—as they often do so themselves. “They all merged with their characters,” says Mortensen, with whom his younger costars enjoyed philosophizing, fishing, and monkeying around. “I found, generally, that whenever I was around the hobbits, I’d be laughing.”

Embodying the true hobbit spirit was a priority for the four, but first they had to figure out what that really meant. “The innocence and naïveté of the hobbits was something I was very intent on capturing,” Boyd says. “And a lot of that came from watching children. If you watch a child who’s just learning to talk, they’ll sit and look at someone as if they can hear every word that they’re saying, and understand it, but they’re not. That’s kind of the way Pippin is.”

For Monaghan, an important element was the physical affection. “They’re very childlike, and they’re very emotional. And they have no qualms about being loving to each other. Whatever they feel, they go with, which I think is a really beautiful way to live.”

But Astin resents the childlike descriptions. “I think Peter looked to the hobbits to be a kind of comedic relief. If you look at the scene in the Council of Elrond when I say”—Astin takes on a goofy tone—“‘Oh, you’re not going anywhere without me.’ To me, that was over the line of being too hokey. And yet I think Pete loved that. He loved the sweetness of that. There’s an element of Sam’s personality that’s staunch and stoic and reserved. And I preferred living in that space more than the Ralph Bakshi [who created the ill-received animated version of Rings in 1978] interpretation of the hobbits.”

Wood shakes his head and smiles, suggesting he’s heard this talk before. “I was so proud to be a hobbit. I walked every day out on that set with such pride. Not only did I love the characters and what hobbits embodied, but I loved you guys.”

“I just wanted to make sure the hobbits were getting the respect,” Astin says.

“I always felt like we did,” Wood responds, taking a bite of a pickled vegetable. “And I think Sam’s innocence is beautiful. A lot of Sam’s comedy is the fact that he’s just so innocent and so pure.”

Samwise Gamgee, the stalwart companion to Frodo, is best known for his devotion to his friend. “Samwise Gamgee is a yeoman—the enlisted soldier whose job is to be in service of the officer that he’s working for. That’s how Tolkien cast him,” Astin says, with marked pride. But there are many sides to Sam, and Astin found himself, at times, at odds with Jackson on just how to portray him.

Astin’s mother, Patty Duke, “hardwired” him to deliver what a director asks for. “My mom raised me to believe that you hit your mark, you say your lines, until such time as the director identifies himself as being unworthy. But Peter Jackson was never going to fall into that category. [But] I felt, interestingly, like I was psychologically caught between Peter’s conception of me and Fran [Walsh]’s conception of me as a hobbit.”

Astin is referring to how much of a roly-poly-aw-shucks hobbit Sam should be. At the time of his audition tape, Astin weighed 160 pounds, and Jackson encouraged him to gain weight. “I remember being in their kitchen at one point, and Fran said, ‘You don’t have to put on any more weight.’ And I remember Peter just kind of cocking his head and looking at me.”

Eventually, Astin reached 197 pounds. “I wanted to be perfect for Sam, but I wanted to be the heroic Sam. When people say, ‘Sam is the true hero of this story,’ I want to have a sense of confidence that maybe if it is true, I can own that. And at 197, I don’t. And at 184, 180, 178, I’m starting to. There were moments, like when Sam and Frodo see the elves for the first time—that, to me, was the ideal look for Sam. I’ll tell you, until I lost 40 pounds, I couldn’t see the character anymore. All I could see was that fat f*.”

According to Astin, Peter had originally wanted to cast an Englishman for his part. “I think he resisted the idea of a Hollywood leading man as being antithetical to the integrity of the spirit of the character.” So the added weight, in Astin’s mind, was Jackson’s way of distancing his character from America’s celebrity machine. “I think Peter senses in me a potential for being a Hollywood sellout,” Astin says. “So he wanted me fat.”

None of this is news to his fellow hobbits. “Sean’s a worrier. He’s a natural-born worrier,” Monaghan says. “I think he gets himself in too much trouble with his own mind.”

Still, the other hobbits have deep affection for him, even if he tends to be the odd man out; the main cause of his estrangement is also part of what they find so endearing—that he’s the only family man in the group.

Astin brought both his wife and daughter to New Zealand for the entire shoot. “The single greatest aspect of working on the movies was having them with me. That was the best, bar none. Being able to feel like I was succeeding as a father and a husband by being able to give them this experience.”

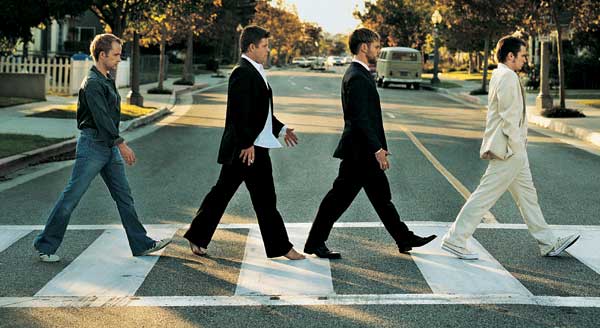

“Having said that, there were real heart pangs about not being able to be one of the Beatles, really. And I would play at it, but they can all drink me under the table—including Elijah. They all carry themselves in the nightclubby atmosphere with real panache. And I’m the Wal-Mart guy: I’m the guy who when the sun comes up in the morning and sh*’s got to get sorted out, I’m the go-to guy.”

“I think the hardest thing for Elijah to do was to dramatize Frodo’s internal psychological battle as the ring is taking effect,” Astin says. “It’s a huge thing for an actor to say, ‘Okay, it’s month nine and I’ve had a nice weekend and now I have to exist in this emotional place of total spiritual, emotional, and psychological suffering at the snap of a finger.”

Wood agrees. “Frodo’s journey up Mount Doom in Return of the King, and what that does to him—it’s literally where he’s at his end. It’s a f**in’ trippy thing to watch yourself so deteriorated and so completely different from who you are.”

Indeed, despite being the most prominent name and the ostensible lead in an ensemble cast, Wood never gave less than 100 percent, according to his fellow hobbits. “Elijah is really optimistic about everything,” Boyd says. “And he’s pretty much up for anything.”

Jackson could rely on Wood’s can-do spirit throughout the production. Wood was fearless, whether it was revealing unguarded emotions for dramatic scenes or abusing his body during stunts. His lack of inhibition even extends to our dinner table conversation, where he suddenly exclaims, with a laugh, “I was known around Wellington for my large testicle. That’s actually a great story.” He then tells about having suspected for years that something was a bit . . . unbalanced, which led to fears of sterility and heaps of self-denial, until, finally, he had his testicles checked in New Zealand. Turns out, he’s fine (no need to go into clinical explanations here). When Monaghan and Astin express reservations about Wood’s candor, he says: “I don’t give a sh*. I had to go through that because I was so embarrassed about it. Now it’s funny. It’s comedy.”

Above ego and self-interest, Wood loves good material—whether it’s music, films, or storytelling.

“He is the famous one in the group,” Boyd says, “so he’s the one that people come over to and ask for autographs. And I think Elijah’s a great role model for that. Seeing how he deals with it—he’s always very noble.” Although Rings has launched Wood to a whole new level of fame, he says the more significant result has been the formation of a new network of friends (which, in addition to the hobbits, includes Mortensen, Bloom, and several of the crew). “Lijah’s always been kind of separate from the Hollywood set,” Monaghan says. “I think now that I live here and that Billy’s been coming over, he’s probably been going out more in L.A. than he ever used to. Because he’s got a few people that’s he’s rolling with.”

Merry Brandybuck is, in the book, the more scholarly of the hobbits. “The first time you see Merry in the whole trilogy, he’s this cheeky chappie,” Monaghan says. “By the end of the third movie, he’s gaunt and thin and pale with long hair and covered in blood. And he doesn’t really know who he is anymore. And, as an actor, for that journey to take over a year to get there was unbelievable.”

In almost every group of friends, there is a loose cannon, the naughty one who draws the others to the edge of bad behavior. In Tolkien’s group of four hobbits, however, there is no such individual. Among the actors who play them, there is Monaghan.

“Dom is a rake,” Astin says, with mock foreboding. “A rapscallion.” Or, as Wood says: “There’s a virile swagger to Dom. He also brings a certain amount of cool and style that’s different from everybody else.”

Monaghan is quick to own up to it. “I probably force people to party a little bit more. I would usually be the spark in the group. If there was an argument going to go on between the four hobbits, which was rare, it would usually be with me.”

After principal photography, the Manchester, England–raised actor moved to Los Angeles, riding high on his Rings experience, but he quickly came down to earth. “I had a terrible first year in L.A.” he says, “Oh, man—rubbish.”

Monaghan arrived, he recalls, thinking, “I’m going to come here and go for auditions, I’m going to pick up a couple of jobs, and people are going to be excited that I’m in Lord of the Rings. They’ll want to hang out.” Instead, Monaghan found himself walking to Bristol Farms, buying some sushi, playing Grand Theft Auto, and going to bed—almost every day. “I was out in the wilderness for probably about eight or nine good months,” says Monaghan, who, without a car, didn’t want to lean too heavily on Wood or Astin.

Moving to the next stage “was the comedown after what had defined me as a person. I got to New Zealand when I was 21; I left when I was 22. And I felt like I did most of my adult growing up there. And we were all in this incredibly close, tight-knit brotherhood. And then you leave . . .” Monaghan says. “And I don’t necessarily want to get treated like the king of the world, but I wouldn’t mind just a little bit of attention.”

Meanwhile, Bloom’s career was skyrocketing, making Monaghan’s situation feel worse. “There was a point when I looked around and every single person I knew was working: Billy was working on Master and Commander; Orlando was flying; Sean, Elijah, and Viggo were all working. I started getting a little bit ashamed.”

Eventually, the darkness lifted: Monaghan’s dedication to various passions—painting, yoga, surfing—as well as a couple of jobs (two British productions) helped him move on. “When I look back on it now, it was a beautiful year, actually. I had amazing insights in the fog of depression. Now I’m just back to being Dom again.”

Monaghan continues to rely on his friendships with the hobbits, especially Boyd, with whom he has been writing an irreverent buddy-comedy that has begun to garner interest from studios. “Billy and I are very, very strongly connected. When we are making each other laugh, I don’t see anyone else in the room.”

Pippin Took is the most impulsive of the hobbits. He’s also the best-natured. Though the Rings production was plagued by almost daily script rewrites, Boyd wasn’t phased. “I could enjoy that actually,” says the Scotsman, who came up with some last-minute lines of his own for his most iconic scenes. “I like things that seem exciting—happening—you know. I liked Pete giggling and giving me pages 15 minutes before I start.”

“He’s got a sprightly sense of humor, and he’s always optimistic, always, I mean to a fault,” Astin says of Boyd. “Even when he decides to be disgruntled for a moment, he can’t quite do it very well.” Which is not to say he’s exactly like Pippin. “Billy’s got a little bit more worldly experience,” Astin continues. “He’s got confidence, grace, and poise. And he consistently delivers for those around him.”

“As funny as he can be, and as irreverent as he can be,” Wood says, “Billy’s also probably the kindest and the warmest of us.”

Boyd is also the hobbit with the least vested in Hollywood. He’s got a Scottish dancer girlfriend, and he says he’s staying put. “I think if you base too much of your life on your career, ninety-nine percent of the time, it will make you unhappy,” Boyd says. “That’s why I still live in Scotland. That’s why I do the things I do.”

For example, Boyd loves to travel, to “disappear where nobody can get you.” Or, this summer, he did a three-day play at the Edinburgh Festival partly as a favor to a friend.

“He refuses to take life too seriously,” Monaghan says. “He’s a little bit older than us. I think Billy’s known for a while you should enjoy yourself in the moment.”

Boyd’s past was no walk in the Shire—having grown up in a housing project in Glasgow, and having lost both of his parents by the age of 15. His father died of lung cancer and his mother “basically never recovered from it,” he says. Raised by his grandmother, he had wanted to get into acting but felt compelled to work, eventually landing a job as a bookbinder, which actually gave him his first brush with Rings—he used to fasten the covers on the books.

By his twenties, Boyd made it to drama school, landed some theater and television gigs, and finally, was cast in Rings. “I spoke to Bill a lot about our destiny after The Lord of the Rings and what that means and where will it be,” Monaghan says. “And Billy’s just like ‘Well, you know, as long as I can live by the sea and I can surf and I can work every so often . . .’ ”

“I think what is sort of the beginning of the end was that we all went back to New Zealand for reshoots on the last film [in June],” Wood says. “That was the last time that we’ll ever film anything for these movies. So that was the beginning of the end of our journey.”

Boyd: It didn’t really feel like the beginning of the end to me. It felt like the middle of the end of the beginning.

Monaghan: Yeah. You know, kind of like the three-quarter-length part of the middle of the end of the beginning.

Over the past four years, the cast of Rings has undergone a 15-month production, reshoots in 2002 and 2003, multiple ADR sessions, and three multiweek publicity campaigns. But, finally, the end is nigh. This summer, the four hobbits joined the rest of the cast for a last round of filming, which included touching up scenes.

“There was a sense in that first movie that we didn’t really know what we were playing. We didn’t know how it would play in the context of the film, because we were filming so much footage,” Wood says. “There were so many scenes and so many different characters and so many plot lines. I think it made it a lot easier going back for pickups, ’cause we had a real concept of what the fabric of these movies were.”

“We got all three scripts when we turned up in New Zealand, and number three was the best. That was the one that Pete was the most psyched about,” Monaghan says. “There’s something so brilliant about the long journey that we take and how all our stories come right back together. There’s something so beautiful about it. But it’s also easily the saddest movie.”

“It was always our favorite,” Wood says of Return. “It’s the part of the story in which all of the characters are given their true test.”

Tolkien’s “Scouring of the Shire” chapter won’t be happening in Jackson’s version, according to the hobbits. “We were really keen to do it,” Monaghan says, but after talking with Jackson, they were convinced that “in the film, the ultimate objective is the ring, and that’s what the audience is invested in. You can’t take them through three films and have the final destiny of the ring fulfilled and then keep them involved for another 40 minutes. We were all pretty bummed out because, yeah, four hobbits riding into the Shire on horses and kicking a lot of people’s asses would have been brilliant. We would have loved it.”

When the hobbits get to talking about how good The Return of the King will be, they develop a gleam in their eyes that is not far afield from that of their fans. “Guys, I don’t know if anybody knows this yet, but they’re releasing the coolest thing in the world,” says Wood, who then excitedly describes New Line’s plan to release extended versions of the first two films so that audiences will be able to see them back-to-back and then watch Return immediately after. They discuss plans to be there, in the audience, that first night.

Monaghan: We’re all going to hang out. We’re all going to work together. And we’re all going to have the opportunity to be brought together as often as we want to do the Lord of the Rings conventions, and other things. You know, I said to [New Line’s] Mark Ordesky and Pete, “When The Return of the King finishes, you have to promise that on a yearly basis you invite the cast to some sort of dinner.”

Boyd: And they both said, “F** you, mate.”

Astin: That’s when they started cutting down his part, you remember?

Wood: Yeah, exactly.