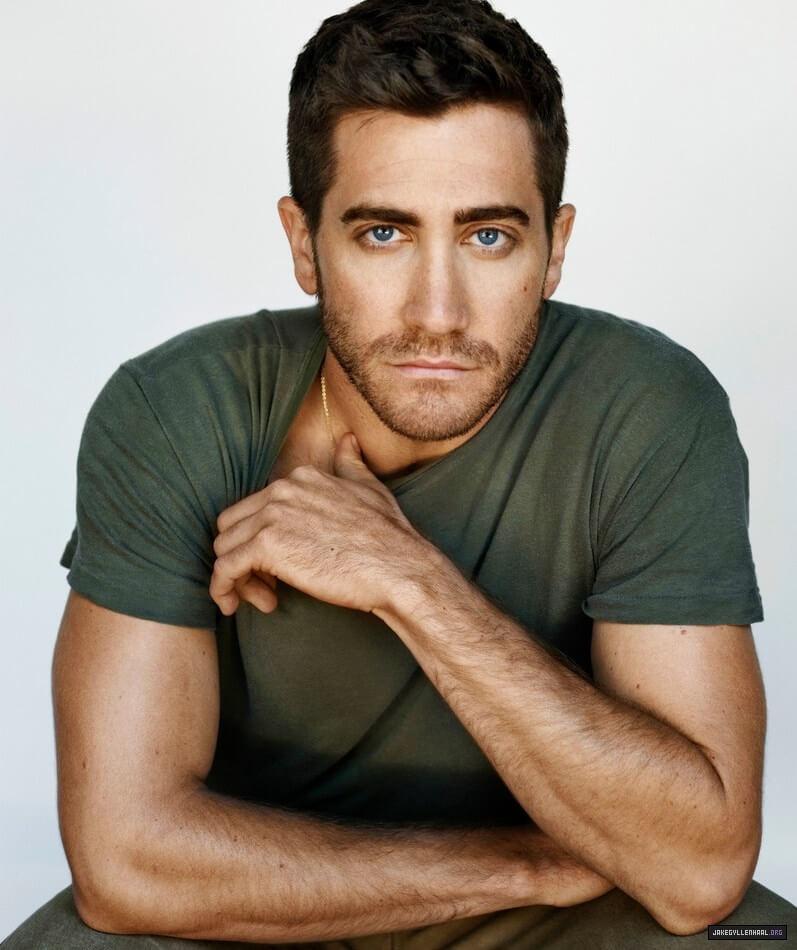

With the new thriller Source Code in theaters now, Jake Gyllenhaal sheds his wide-eyed wonder years and casts himself as the next leading man.

Jake Gyllenhaal proves to be a man of his word, unfortunately. Yesterday he promised me a “really f**ing hard climb,” and that’s what he’s engineering now.

Jake Gyllenhaal is something of a cardio monster. You might not guess this at first glance. At 6 feet and about 180 pounds, the 30-year-old is visibly in shape, but he doesn’t sport the typical road-biker, my-body-fat-is-lower-than-your-mortgage-rate frame. For his past two action roles, as the title character in Prince of Persia last spring, and as Captain Colter Stevens in Source Code, he’s cultivated more of a military build. But left to himself, what he likes to do is run or bike. Inevitably, though, he pushes hard, even too hard. He says he suffered shin splints before he started barefoot running. “I’ve had to teach myself to slow down a bit,” he confesses. “Because I get so into it, it becomes a real addiction. But it’s like a New Year’s resolution.”

“To exercise less?”

“To sit down and read a book. Life’s not a bike ride. I wouldn’t say exercise less, but sit with myself.” Good thing there’s the action-star loophole — Jake believes he can “sit with himself” while he’s running. “It’s not: ‘I’m having a sh*y day and I’m going to go for a run,’ but ‘I’m having a sh*y day and I’m going for a run and I’m going to try to work out what’s going on.’ Not just get my serotonin levels up and feel good. I’m going to think about things. And the only way you can do that is to slow the pace down.”

“It’s steeper if you take the inside.” Partly to distract him, I ask if he has any more climbing advice. “I like to think of my toes as always moving forward,” he says. “Don’t push down. Try to even out the forces between pushing and pulling. Find a cadence and stay in it.” This works almost instantly. “Stay relaxed. You ever see the riders in the Tour de France getting up in the saddle? They’re not rocking from side to side. Their spines are loose, and they look like fish.” He stands on his pedals and turns to me. “When I start getting tense, I breathe out.” One arm at a time, he lets go of his handlebars and flicks his hands. “I carry a lot of tension in my hands, so I do this a lot.” Soon his advice starts to have a positive effect on his pace, too, and he shoots off up the road.

Gyllenhaal’s newest movie — the fast-paced Source Code — comes at just the right time for the actor. Despite some misfortune at the box office last year — Love & Other Drugs, Prince of Persia — Jake clearly harbors leading-man ambitions. But leading man is a tough job to get. First of all, nobody really knows what the next one will look like. And, worse, you can’t always spot it the first time — a scary and paradoxical fact that leads industry types to place huge bets on proven losers. The Val Kilmers, Paul Walkers, and Josh Hartnetts of this world. It took George Clooney three tries to get a winner: The TV doctor tanked in two big-budget films (the gloomy The Peacemaker and the leaden Batman & Robin) before connecting as a smooth-talking con man in Out of Sight, a midbudget caper directed by Steven Soderbergh, whose three subsequent capers with Clooney grossed $1.1 billion worldwide.

“It’s a funny term, leading man,” Source Code‘s coproducer, Mark Gordon, says. “Sometimes it’s leading man, sometimes it’s leading boy, sometimes it’s leading boy-man. What’s great about this movie is that Jake is a man-man.” Gordon first worked with Gyllenhaal on The Day After Tomorrow, when the actor was 21. Gordon remembers a smart kid who did an impressive amount of preparation. (Gyllenhaal recalls it reaching obsessive levels. He laughs about it now. “I remember somebody pulling me aside to say, ‘Don’t get your tuxedo ready, Jake. We’re making a disaster film.’ ”) Ever since, Gordon has been looking for the right project to harness that drive. When he found the Source Code script, he brought it straight to Jake.

It’s the first movie in Gyllenhaal’s career that doesn’t to some degree trade on his heartthrob capacity for doe-eyed ingenuousness. “In Source Code there’s a side of Jake we haven’t seen before,” director Duncan Jones, who is David Bowie’s son, says of the actor. “He’s played leading men before, but I’ve often felt there was an unnecessary tone to the characters, eyes wide open, looking in awe at stuff. Those roles don’t seem as proactive. This time, there’s a real leading-man quality, that Harrison Ford–Indiana Jones trait of just getting on with it as the world happens around him.”

Once Gyllenhaal read Source Code, he couldn’t get it out of his mind. And when he saw Moon, Duncan Jones’s first feature film, he knew he’d found a like-minded collaborator. So he set about convincing the producers to bet the budget on the largely untested director. “Duncan just seemed like the perfect director for it. Meeting him, I was struck by what an auteur he was. Duncan has this inherent patience, a kind of quiet, stoic, searing quality. His films have the same quality — a kind of hum underneath them — that ends up really messing with the audience’s mind.”

Gyllenhaal is in nearly every shot, essentially carrying the movie: His perception of reality is the audience’s; we experience the whole thrilling, nuanced ride through Gyllenhaal’s eyes. The movie presents the actor with some unusual challenges — one that moviegoers would never think to ponder. Like, how exactly do you prepare to rip apart the space-time continuum, as Gyllenhaal must do over and over? “A lot of times, for the transition between the reality of the train and the reality of the pod,” he explains, “I’m completely out of breath. And I tried to make that worse. I’d do kung fu to wear myself out, basically every possible combination over and over again, but holding my breath instead of breathing like you normally would. So I’d get superdizzy and keep going, jump in the pod still holding my breath, and as they go into the scene, I’d be like, ‘Hwaaah!’ It required a lot of physicality.”

Gyllenhaal likes talking about the how-to, technical side of his job, but he’s reflexively modest about his new role and its prospects for placing him on the very short list of Hollywood’s elite actors. The truth is, he’s growing older. “I think it’s just a period of time in my life. Most people my age are like, ‘All right, what do you want to do with the rest of your life? What do you want to say?’ ”

To an actor, being called a natural can sometimes sound like an insult, as if all he has to do is simply cough up a performance. But for Gyllenhaal, the second child of a director and a screenwriter, film instincts are practically prenatal. “Someone asked me yesterday, ‘Hey, man, how do you get into this business?’ And I…I…I…” (And this is all it takes for Gyllenhaal to convey the existential confusion the question provokes.) “…I totally could not tell you. From the moment I’ve breathed oxygen, I’ve been involved in it.” He made his film debut at 11, as Billy Crystal’s kid in City Slickers. He went to high school at Harvard-Westlake in North Hollywood with older sister Maggie, Jason Segel, and more recognizable surnames than most award-show programs. Back home his parents had an apartment they rented out to friends; at one point during his youth, Steven Soderbergh was living in their garage.

On some level, he says, he feels like he’s still in the family business. “I grew up in the house of storytelling. And that lends itself to religion in all different ways. My mother” — screenwriter Naomi Foner — “always stressed structure, the story’s structure. And my father” — director, poet, musician Stephen Gyllenhaal — “would make up stories right before we went to bed. For a long time, I thought that bubble gum literally grew on trees and that artichokes were invented by a guy named Arthur who choked on the strange stringy vegetable.”

Gyllenhaal’s bio reminds us that though Hollywood may be the headquarters of a global industry, it’s still a small town. It’s easy to view his dating life (with Taylor Swift, Reese Witherspoon, Kirsten Dunst, Jenny Lewis, et al) in this context. But now that he’s reached the age where he worries about what he wants to say, he’s also discovered what he does not. In the past he has had a tendency to gush — about Witherspoon’s kids or the dog he shared with Dunst, for instance. But now, apparently, he is rebranding himself not as one of Hollywood’s most eligible bachelors, but as its most discreet.

His parents divorced in 2009, after 32 years of marriage, and Jake is extremely close to Maggie. When asked about people he admires, Jake’s first answer is Maggie’s husband, the actor and sometime costar Peter Sarsgaard. In fact, it was Sarsgaard’s recent dedication to barefoot running that encouraged Jake’s. “My brother-in-law is a huge inspiration, truly one of the best artists I know. And it’s not that he’s competitive, but he looks within himself, and he loves running because it gives him an opportunity to do so in the same way he does in his work.”

From the outside it may look as if Jake has had the world handed to him on a celluloid platter, but up close he’s a man of intense drive and fierce loyalty. At one point, I ask him about one of his friends, Lance Armstrong, who’s having a rough winter, with the Feds’ continuing allegations of widespread doping. It’s impossible to mistake the vehemence of Gyllenhaal’s support. “All I know about him is he’s a wonderful guy to me,” he says. “He does incredible, incredible things. And anybody who’s that extraordinary is bound to be doubted. Because what he does is rare.” He quotes playwright Tony Kushner, and his insistence in a stage direction for Angels in America that the wires holding up the angel be clearly visible to the audience. “That’s about acknowledging that it’s not magic, that there is a reality. I suppose we’re all looking to take the magic away. But speaking for myself, we all desperately want the magic to exist. It’s like, ‘How could somebody be such an incredible athlete? I want to see the wires! Where’s the wires?’ I see this in performing: Like Meryl Streep, why the f** is Meryl Streep so amazing? Why is she worlds beyond so many other people? Nobody accuses her of anything other than being extraordinary.”

In person Gyllenhaal is distractingly attentive. A couple of times I have to stop him from interviewing me, asking about my children, interviewing techniques, my love life. “I’ve done interviews a few times,” he says, with genuine professional curiosity. He lists a few: the NASA engineer Homer Hickam, before October Sky; Jamie Reidy, the salesman who inspired Love & Other Drugs; Robert Graysmith, the cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle, for Zodiac. “When I’ve been playing a real person, I go talk to them to find out what’s really going on, for something I can use, not just idiosyncrasies or movements or things like that — what’s actually happening and how they feel. It’s a very hard thing to do.”

He admits his ties to his Swedish heritage (including frequent mispronunciation of his last name) can be somewhat shaky. “I was asked once by a Swedish interviewer to name five famous things from Sweden,” Gyllenhaal says. “And I was like, ‘Volvo…Audi…the Cardigans.’ And it stopped there.” He smiles, that slow-dawning, lopsided grin, somehow both cocky and sheepish, unaffected and completely at ease. It’s a gift of his, a quantifiable professional asset, like Julia Roberts’s. It’ll fit perfectly if he ever gets around to making the Joe Namath movie that Namath likes him for. He did get a brief interview with Namath, he tells me, with genuine excitement. “I mean, come on. It’s Joe Namath. I asked him about passing, like, ‘How’d you get so good at it?’ And he said, ‘You know, Jake, when I think about throwing the football’ ” — and here Gyllenhaal doesn’t imitate Namath’s accent so much as slow down his pace, giving an accurate sense both of hanging on Namath’s every word and also wondering if he’ll make it through the sentence — “ ’I just look where I want the ball to go…and then I throw it there.’ ” Gyllenhaal cracks up. I don’t mention that Audi is, in fact, headquartered outside Munich, but I do call him on his Swedish cred.

“Wait a minute, though, Jake. Your mom’s Jewish, right? You had a bar mitzvah and everything.” “Yes,” he says. “I have a great connection to both Swedish meatballs, and kasha and gefilte fish.” “Honestly, gefilte fish?” He backtracks. “Well, herring. Which is a little Swedish too.”

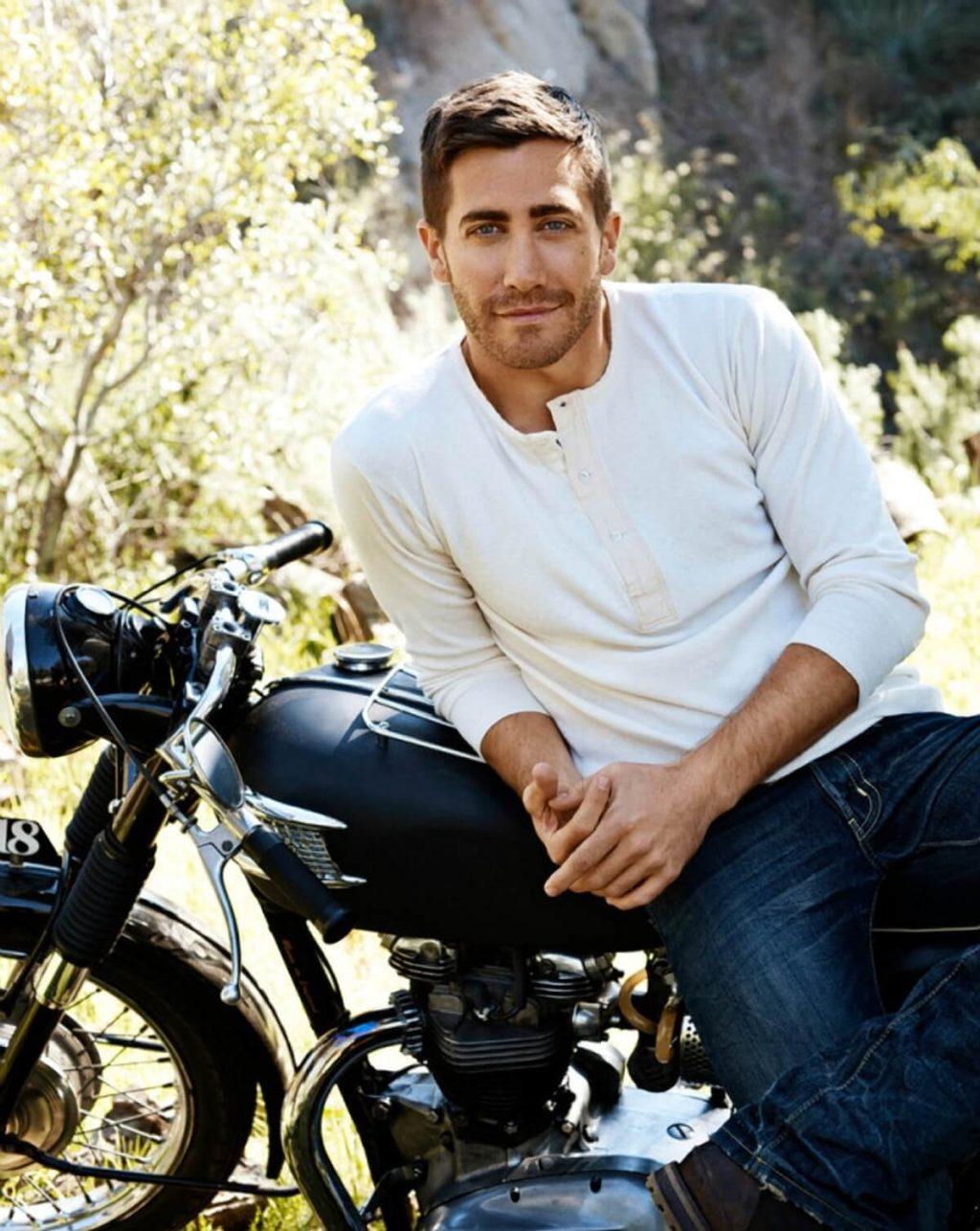

Gyllenhaal arrived on a motorcycle: The black helmet sits beside him; his black leather jacket hangs over his chair. He’s wearing a gray crewneck pullover. As an outfit, it lies somewhere between anonymity and invisibility. But this doesn’t stop the woman from coming up to the table to ask, in an accent that might actually be Persian, if Gyllenhaal was really in Prince of Persia. She’s right, he tells her, and the woman cheers, demurely. Gyllenhaal seems accustomed to being the correct answer to a bet. “What did you win?” “Drink after work.”

People come up to Gyllenhaal a lot, of course. And after so many movies he’s starting to recognize types. People who’ve just seen Donnie Darko, for instance, often approach with a thunderstruck look. “It’s as though they’ve just been initiated. I’m like, ‘I don’t want to know what happened. Don’t go there.’ ” Sometimes the reactions can stop him short. He’s getting the feeling that Jarhead, in which he plays a marine trying to hold it together during Desert Shield, is finally finding its audience: Someone came up to him recently to say that his brother had enlisted because of that movie. Encounters like this shake him out of his professional cocoon. Brokeback Mountain remains a touchstone for Gyllenhaal: an idyllic shoot, a cultural watershed, an Oscar nomination, a permanent reminder of the tragic death of his costar, all of it tied to, and driven by, a powerful story. “I’ve been taught that stories are very powerful. And I feel like I have a huge responsibility,” he says. “I’ve been testament to it, too. When we did Brokeback Mountain, I had no idea. I had no idea I’d be able to have that much power over somebody’s life.”

In fact, it’s so powerful that Gyllenhaal still gets people coming up to him to say that they would never see it. “Seriously? People go out of their way to tell you to your face?”

“I get that all the time,” he says. Then, adopting an almost imperceptible slouch, he reenacts the overshare. “‘You’re that guy in that movie, right? Brokeback Mountain, right?’

‘Yeah, I—’

‘I mean, I didn’t see it. But you’re that guy.'”