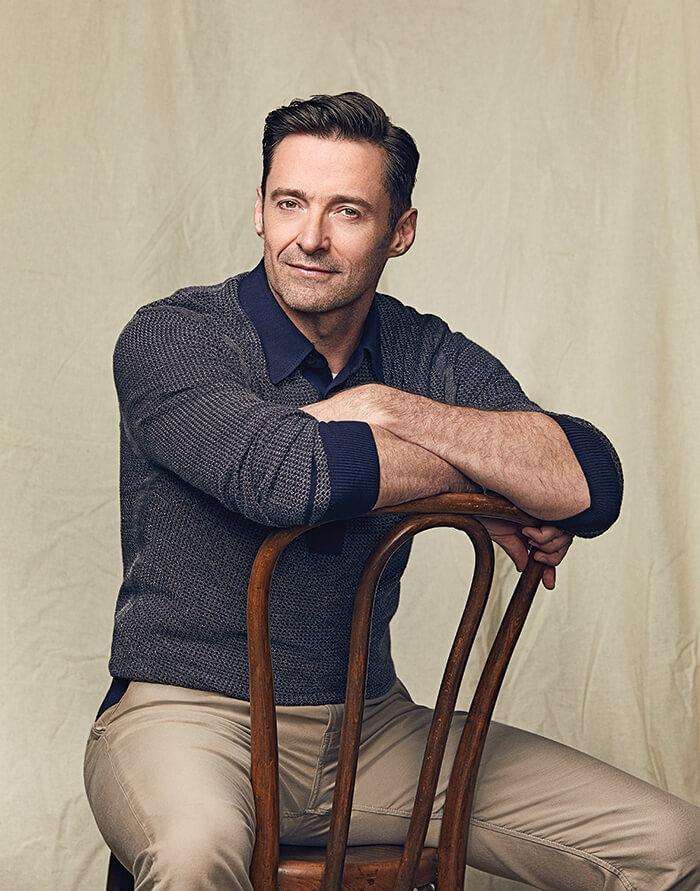

On a blustery late-summer day, Jackman walks into Perry St, a posh SoHo eatery overlooking the Hudson. Even dressed down in a gray T-shirt and cargo pants, the six-foot-three actor with the gleaming smile and jet-black hair is every inch the movie star. He cuts a figure so dazzling that even here, a gathering spot for 1 percenters, patrons will glance over at the corner table where Jackman parks himself, hoping to catch a glimpse of the actor in an unguarded moment.

Jackman looks revived after four months spent traveling with his wife, Deborra-lee Furness, and their kids, Oscar and Ava, to Greece, Italy and their native Australia. He’s ready to plunge back into work. Next week he’ll fly out to Colorado to spend time with former Sen. Gary Hart, whom he’ll be playing in Jason Reitman’s The Front Runner, and then he’s back to New York for four days of reshoots on The Greatest Showman.

Even Jackman sounds surprised that the Barnum musical got made, confessing that he put the odds at less than 50-50 that cameras would ever roll. Yet there was something about the story of this self-made man, who climbed the social ladder by displaying bearded ladies, tattooed men, sword-swallowers and other curiosities in his traveling circus, that he couldn’t shake. He had a kind of chutzpah that was infectious.

“He created this world that no one had even thought possible,” says Jackman. “He really, for me, epitomized the idea that your imagination is your limit in a time where things were very rigid and when the social position you were born into was the one you were stuck in.”

It’s been quite a year for the actor. Not only is Jackman hoofing it up as Barnum, but 2017 also saw him bid farewell to his signature role of Wolverine. Logan, his swan song to the world of mutants, was a critical and commercial smash, a bloody neo-Western that featured the clawed hero beaten up, grappling with his own mortality and staring down the neck of too many empty whiskey bottles.

“This was not a film about selling lunch boxes or action figures,” says director James Mangold. “It was oriented toward adults. The goal was to make something gritty that was also a character piece.”

Jackman says that despite playing Wolverine in nine films over nearly two decades, he had a hard time finding the heart of the cigar-chomping bad boy.

“I wish I’d started playing him like that 17 years ago,” he says. “So there’s some sense of missed opportunity, but when I saw Logan, I sat there and I did have tears in my eyes. The main feeling I had was: “There, that’s the character. I feel like I’ve done it now.” And I was calm and at peace, but I’m going to miss that guy.”

Jackman could be forgiven for feeling uneasy in those initial X-Men films. He was a last-minute substitute who only got the part after Dougray Scott, the original choice, was forced to drop out when Mission: Impossible 2 went over schedule. It’s an example, Jackman says, of the role that fate played in making him a star. He’d auditioned for X-Men nine months before shooting was scheduled to start and failed to land the gig. A chance visit to Hollywood changed his life.

“I was only in L.A. to do the paperwork for the adoption of my son,” Jackman remembers. “I had an agent at the time, and I gave him a ring and said, ‘I’m in town for a week. Is there anything I can read for?’ He said, ‘I’m hearing some whispers about [X-Men] — let me make a few calls.’”

Patrick Stewart vividly remembers meeting Jackman when he came in to do his screen test.

“We’d been shooting for a week or maybe more, and we were running out of stuff to shoot without someone to play Logan. One morning this slender, pleasant-looking guy with a strong Australian accent is introduced to us all,” recounts Stewart. “He spent 15 to 20 minutes chatting, and by the time he was called to do his reading, we’d fallen in love. He charmed everybody.”

Jackman wasn’t as confident. He thought he’d blown the audition. As he left, he whispered to Stewart, “You’re never going to see me again.” Four days later he was stunned when he got a call telling him they needed him to come back.

At a time when Hollywood movie stars are a rare breed indeed, Jackman has leveraged the Wolverine films to bankroll a diverse number of personal projects and has emerged as one of the last of the bankable leading men. It’s a status he’s worked hard to achieve, not just in the care he’s taken in selecting films but in the hours he spends at the gym bulking up to superhero size.

“People always say to me, ‘Why are you in such good shape?’ and I always answer, ‘If I told you that you were going to be on film on a 40-foot screen with your shirt off, you’d be in good shape too.’”

Even as Wolverine has kept him on the A-list, the actor hasn’t felt the need to add another film franchise to his stable. At one point, when the James Bond producers were casting a net to find a replacement for Pierce Brosnan, Jackman rejected their overtures.

“I was about to do X-Men 2 and a call came from my agent asking if I’d be interested in Bond,” recalls Jackman as he dives into a plate of salmon. “I just felt at the time that the scripts had become so unbelievable and crazy, and I felt like they needed to become grittier and real. And the response was: ‘Oh, you don’t get a say. You just have to sign on.’ I was also worried that between Bond and X-Men, I’d never have time to do different things.”

Instead of trying to land a 007-style crowd-pleaser, Jackman has focused on proving he can act without the aid of adamantium claws.

“I always tried to do different things,” he says. “But there was a time between X-Men 3 and the first Wolverine movie when I could see the roles getting smaller. People wanted me to play that kind of hero part exclusively. It felt a little bit claustrophobic.”

To battle typecasting, Jackman has alternated between stage and screen, playing a variety of roles in a number of genres.

“He has such a humongous range,” says Mangold, who has worked with Jackman on three films. “He’s like a fine musical instrument. He can play comedy and go light, but he’s also capable of delivering a performance of tremendous power. He’s got this incredible masculinity and strength and the courage to throw that all away and do a musical on Broadway.”

The Greatest Showman continues the actor’s push to demonstrate his versatility. He proved he could hit some high notes in Les Misérables, but the Barnum story required another approach. It’s more upbeat, with a family-friendly vibe.

Barnum’s edges, such as getting into feuds with family members and his semi-exploitation of people with physical deformities, have been largely sanded off in favor of emphasizing his razzle-dazzle.

“We like to say that we made the movie that Barnum would have liked to make,” Jackman says.

And then there were the technical differences. Whereas the Les Misérables cast members were shot performing their numbers live, The Greatest Showman had the actors sing along to a recording, the approach favored by most movie musicals.

To get in shape for the dancing, the cast did 10 weeks of rehearsals, blocking out elaborate routines that find Jackman, Zac Efron, Michelle Williams and the rest of the actors waltzing across rooftops, juggling liquor bottles and high kicking around a barroom, and doing backflips and jazz hands across the circus stage. They discovered that often their voices were better when they had just gone through a strenuous dance routine, so Gracey had a recording studio built on set to capture them at their best.

“Vocally, sometimes you have those ‘I can do anything’ days, and the next day you’re at 80%, so on those days when you’re feeling great, we would just pop over to the studio and record,” says Jackman. “There’s a couple of bits where I sing notes that I’ve never sung. I couldn’t have done that live.”

Zendaya, the Disney Channel star who plays a lovestruck trapeze artist in the film, marveled at the warmth with which Jackman treated everyone on the set — from his big-name co-stars to the production assistants and gaffers. He also imparted some advice to the 21-year-old actress.

“I was trying to figure out what project to do next, and he told me don’t do it if it doesn’t make you happy,” says Zendaya. “You have to make your own decisions. Don’t listen to other people. Just trust your gut.”

Others who have worked with Jackman echo Zendaya in noting his generosity. He has a politician’s knack for learning names — at lunch, for instance, he engages in a lengthy back-and-forth with a waiter about their respective families, greeting him like an old friend. But he insists that all the stories that talk about how “nice” he is are blowing things out of proportion.

“It’s the way I was brought up,” says Jackman. “My parents always treated people with great respect. My father never yelled, and I admired that. I also genuinely love the family aspect of what we do, and I feel more comfortable being relaxed and myself with everybody, rather than a feeling of ‘Oh, I’m a big actor; you can’t talk to me.’ My way of connecting — maybe people attribute it as being nice, but it’s just being a normal person.”

The Greatest Showman isn’t just a risky commercial proposition, it could also signal a pivot in Jackman’s career. It’s the first time since breaking into the business that he doesn’t have an X-Men film or spinoff on the horizon. That said, Fox doesn’t seem as eager to close the door on future Wolverine adventures as Jackman is.

“We’re going to stay open-minded,” says Snider. “If there’s an inspired way to bring Hugh Jackman back, we’ll know it when we see it, but it would have to be an idea of integrity that we all wanted to do.”

Looking ahead, the actor wants to keep singing. Emboldened by the success of “Hamilton” and “Dear Evan Hansen,” he’s itching to return to Broadway and is developing an original musical.

“A bad musical stinks to high heaven, but when a musical works, there’s nothing like it,” he says. “People are screaming and cheering. Nothing I’ve found has matched it. By the end, as you take the curtain call, there’s no sense you’re in front of strangers. It’s an intimacy you get that’s more intense than you have with people you’ve known for many years. It’s everyone coming together and opening their heart.”

Jackman has loved the theater since he saw a high school production of “Man of La Mancha” starring Hugo Weaving, a classmate at the time. He immediately bought a cast recording of the Broadway production, learning every word. The effect was profound, and growing up, Jackman became determined to have a career onstage. After going through drama school, he felt like he’d earned his big break when he was cast as Curly in the West End production of “Oklahoma!”

“I remember being at the National Theatre doing that show and walking across Waterloo Bridge thinking this is as far as my dreams have got me,” says Jackman. “I was 28, pretty much having reached most of the goals that I’d set for myself. I was always very vague on the Hollywood thing. I felt like if I pinned all my hopes on that, I was destined for disappointment.”

Movie stardom may have come to him despite those initial doubts, but some things haven’t changed. Like Barnum, Jackman comes alive in front of an audience. Even after decades at the center of popular culture, he still gets a thrill in those moments before the curtain rises.

“To this day when I’m doing stage work, I go down to the wings even if I’m not on first to hear the crowd shuffle in,” he says. “It’s the height of excitement as the orchestra starts to play.”