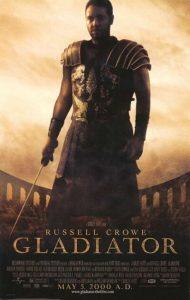

Rating: 3 of 5

Gladiator is more interesting now then it ever was when I first saw it in May of 2000. Because now I have the context of Ridley Scott’s later films (Kingdom of Heaven and Robin Hood) so it’s fascinating to see him working out a particular aspect of his world view.

The movie first:

I never loved Gladiator. Didn’t even like it half as much as apparently everyone else. Possibly because I’m not that impressed with Russell Crowe. Possibly because it felt like it was reaching for some grander substance and significance but fell woefully short. Possibly because Joaquin Phoenix is creepy in it. Probably because of all three.

It was the first movie, though, to use the fast motion cameras in action sequences that are now fairly standard, so it’s got that going for it.

But the writing isn’t exceptionally strong. First of all, you do not enter the Elysian fields through a door. That always irked me. Also, there’s a couple of glaringly lame lines and the writing as a whole is kind of simplistic (let’s not even mention that Russell Crowe named his character himself). Plus there’s a weird logic gap in that Maximus has known Lucilla and Commodus for at least 10 years and yet has never been to Rome.

And I never liked the editing much. I’ve never understood the shot where the hero is unconscious, floating over the ground in some sort of suspended movement (also seen in A Knight’s Tale). It’s weird and not good at conveying anything the director is trying to say. There’s also random shots that aren’t coherent with the main focus of the scene. All of the editing with the wife and son feels disjointed. And I never liked they way it cut to Crowe walking through the Elisan Fields (which also don’t lead to a door, for the record).

There was just so much in this film that I always thought could be more sophisticated and sharper and stronger. The performances were all good, though.

That’s mostly what I noticed this time around. For the first time I understood why everyone was so impressed with Connie Nielsen’s performance. She’s like a queen, especially at the end. I never really bought her romance with Crowe (still don’t) but I liked his line about how strong she’s always been because she replies she’s tired of being strong. She’s this complicated, really fascinating woman trapped in a man’s empire and she handles herself with grace and strength and power and subtle manipulation and horrible surrender. Crowe and Phoenix and all the supporting players are all good, but she’s amazing.

| Writing: |      |

| Characters: |      |

| Performances: |      |

| Directing: |      |

| Production: |      |

| Overall: |      |

The examination of Scott’s psyche:

As I mentioned above, I think this movie becomes even more interesting in retrospect because it’s the first time Ridley Scott is really exploring his idea about virtue belonging to the common man.

It’s interesting to me that Maximus is a simple man. He has the greatest honor laid on him of the three heroic characters, with all of Rome at his feet, and still all he wants is to go home to his wife and son. Even after Commodus comes to power, he doesn’t want to overthrow him or restore order or have anything to do with power. He wants to kill him and be on his way into the afterlife.

(And you can see in Lucilla the precursor to Sibylla and the parallels of their young sons.)

Maximus wrestles with the responsibility thrust upon him, with sorting out how to wield the influence he commands and why he even should. It’s less of a dilemma for Balian, who has an understanding that a man should do good in the world, make it a better place, before the story even takes off. It almost feels like Scott has figured out what he’s trying to say and how to go about saying it. Balian doesn’t hesitate to take authority or to do something good with it and he has both a father and a king to teach him.

By the time Robin Hood shows up all men of power are corrupt. The common man apparently doesn’t need someone to teach him to wield influence or make excruciating decisions to maintain his integrity. Robin Hood is subversive rather than authoritative, able to affect change without obtaining power. Though he still wields a great deal of influence, and he resists taking on even that role. Overall, it’s a more cynical story than the others, a progression in this line of thought about the corruption of the powerful and the simple virtue of the common man.

I’m curious to see where Scott will take it next or if he feels he’s said his peace.