Chris Pratt’s rise to fame is so improbable he sees it as divinely ordained: the friend who sent him a ticket to Hawaii, the stranger who led him to a church, the actress he waited on at Bubba Gump Shrimp. Recalling the leaps of faith that turned him from a door-to-door salesman into a box-office king, Pratt considers what he has to prove now.

Chris Pratt wanted to cook me lunch. And not just any lunch—a lunch made from an animal that Pratt himself had killed, in Texas, where the mesquite blooms and the wild boar does not care nor even know that the handsome man sighting the scope of a .25-caliber Winchester is one of the biggest movie stars in the world. And Pratt did kill that animal. And dressed it and shipped it back to this beautiful house in the Hollywood Hills, where he lives with his wife, actress Anna Faris, and their four-year-old son, Jack. But something went punk at the butcher, and the meat was going to take a lot longer to prepare than Pratt had expected—“Most of it’s being turned into jerky anyway”—so the steak Pratt was basting on the counter in his modern kitchen had in fact been purchased at Whole Foods. “I could tell you this is the boar I shot, and who would know, but, dude, I’m not gonna lie. This is not that boar, but this boar stands for that boar.”

Do you consider yourself a good cook?

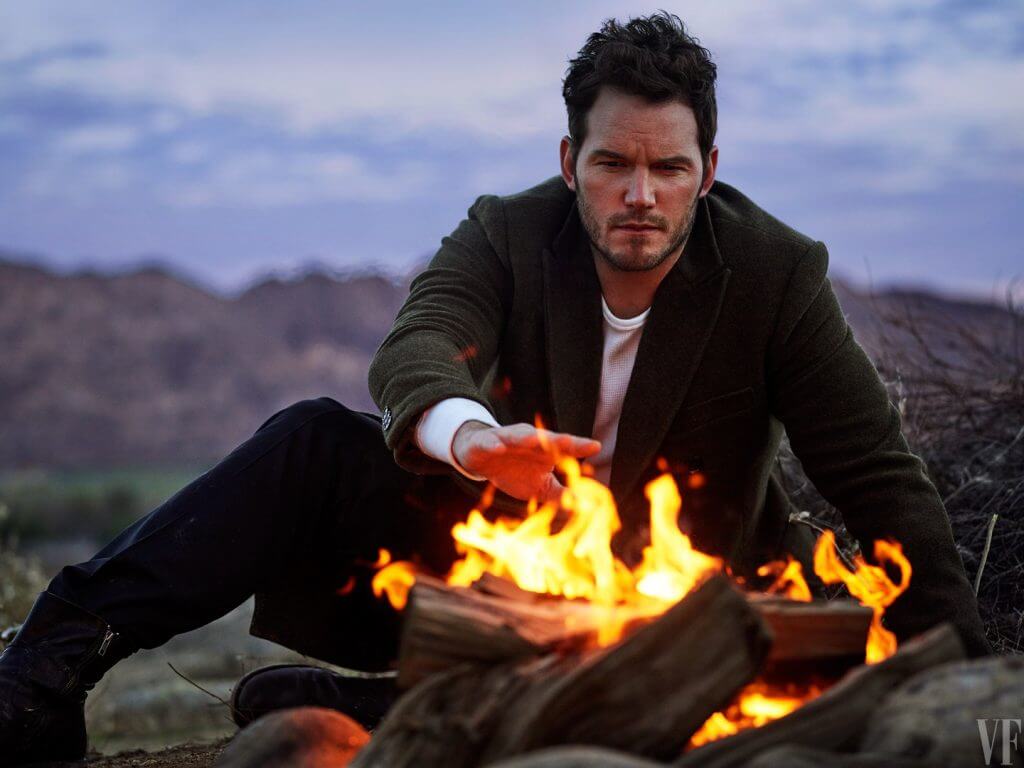

Pratt laughed. He was wearing a flannel shirt and jeans and had let his beard grow to stubble. No shoes, just socks. He’s a big guy, six feet three in boots, in shape, and has the knock-around ease of a regular guy drinking campfire tequila.

“I can make three things,” he told me. “Meat. Omelets. Fajitas. This here I’m making is a wild-boar taco. I got the recipe from my brother-in-law, because that guy knows everything.”

It was a Sunday. Pratt seemed relaxed, probably because he’d decided to take a hiatus. For a decade, he’s done nothing but work, stumbling from film to film after making his name on television. He played Andy Dwyer, the friendly chubby boyfriend on Parks and Recreation, before executing a miraculous switch to action hero, in 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy. It’d be like George Costanza turning into Harrison Ford. And Pratt is compared to Harrison Ford. Though Pratt is funnier. Looking for the proper mix, I’d say Bruce Willis with a dash of Seth Rogen. He can play deadpan wiseass better than just about anyone. He’s on the short list of actors who can do pretty much whatever they want.

Pratt’s decision to take a break results partly from some advice given to him by a childhood hero, Jim Carrey. “There’s very few people in the world who I can expect to understand exactly what I’m going through,” Pratt said. “Jim Carrey is one of them.” Pratt took Carrey aside at a party last year and basically asked, What do I do now? Carrey said, “There’s going to be a point in life where you’re going to have to prove that your family is more important to you than show business.” It’s put the actor in a mood to ruminate, recollect, make connections. At 37 years old, Chris Pratt can finally see his life as a story.

Big Time, Small Town

I asked Pratt about his father. In articles, he comes across as a kind of Paul Bunyan character.

Was he really a goldminer?

Pratt was chopping parsley. I suddenly understood why he’d chosen to cook during our interview. It gave him something to do with his hands while his mind wandered.

“He was a taconite miner in Minnesota,” Pratt told me. “He worked in iron ore; that’s a big industry. We moved to Alaska so he could work in gold mines. That’s how we operated as a family—we’d just make a decision, pick up, and move.”

After a few years, when Pratt was six or seven, the family settled in Lake Stevens, Washington, the Seattle exurb that became Pratt’s beloved hometown. It was nuts for wrestling. Like football in Texas, every kid sized up from eight or nine by the high-school coach. Pratt would captain his high-school team. At one point, he was a top wrestler in the state. When I asked if he’d ever had his ass kicked—because having your ass kicked is character-building—he nodded sadly. “I’d be devastated,” he said. “Because I put everything into it, and if a kid beat me . . . but it’s good. It’s a great sport because you have to stand there and shake a guy’s hand. You look him in the eye, then his arm gets raised. No excuses. You get beat and think, F**!!! Then come back and wrestle him again. I wrestled the same kids for 10 years.”

I asked Pratt if he played high-school football. He has the aura of big-time, small-town. He told me that his father had been a star player in his own day. “He was bigger than me, much bigger, and he’d light up the stadium when he carried the ball. He wore number 76, and for years I thought the gas station was named for him. So of course I played.

“I was a great football player,” he said, then stopped and looked at my recorder. “Don’t say I said that. But, dude, I was a great football player. I was a fullback and an inside linebacker. I never had the speed to play college. But I loved it. I don’t think anything will ever take its place. The competition, the team. You get a little bit of that in acting. You get it with action films. You have to train, be in shape. I think I learned more about how to handle myself as an actor playing sports than I ever did in theater.”

Theater? How did that start?

Pratt’s brother. And he’s important. He’s got a sister who still lives in Lake Stevens, but Pratt’s brother, three years ahead in school, is the key figure in his life. If you were to look at a picture of the Pratts in the early years, you’d see Dan junior, known as Cully, doing something heroic—he’s now a cop—with Chris in the distance, wide-eyed. “He was hands down the best big brother anyone could ask for, super-supportive and always helped me, and loved me, and took care of me,” said Pratt. “We spent our entire childhood, eight hours a day, wrestling. One Christmas, he was in a play, a musical, and sang, and it knocked everyone’s socks off. My mom was crying. And I was like, ‘That’s what I want to do.’ ”

By senior year, Pratt was wrestling, playing football, starring in plays, and writing and acting in every kind of assembly. “We did Grease and we did Michael Jackson’s Thriller and ripped off S.N.L. sketches,” he told me. In other words, Pratt was that rarest of figures. The high-school Renaissance man. Friend of the outcast, confidant of the powerful. Neither bullied nor bullying. An exchange between Pratt and his wrestling coach has been repeated until it’s become legend. According to Entertainment Weekly, the coach asked Pratt what he planned to do with his life: “I was like, ‘I don’t know, but I know I’ll be famous and I know I’ll make a s* ton of money.’”

When I tried to drill down on this he talked more about his father. He’d been a high-school star and lived off that for the rest of his life. “I guess that’s what I planned to do,” said Pratt.

During Pratt’s senior year, his father was diagnosed with M.S., which runs in the family. “He was beyond wanting to accept help,” said Pratt. “If left untreated, it can be devastating, and he left it untreated. For a couple of years he had symptoms, I think, but didn’t say anything. Every once in a while he’d wear an eye patch and say he got something in his eye at work, but it was because he had double vision,” a symptom of M.S.

Dan Pratt Sr. died in 2014. When I asked Pratt if his father got to enjoy his son’s success, he said, “Some of it. He watched a lot of TV in his final years. That’s pretty much all he did, just sat in front of a TV. So, yeah, I think it made him proud, and it was cool that I got to find some way to connect with him, because he was a hard man to connect with.”

Pratt’s mother worked in the Safeway—there was not a lot of money. The Pratts lost their house while Chris was in high school. They rented a place until he graduated, then moved into a trailer. They offered Chris a sleeping loft in a shed out back, but he became roommates with a friend instead. He was thinking of joining the military, but, again, his brother: “He ended up going into the army and told me not to. I think he saw something in me. I was a peculiar kid. I was very much an individual and happy to be an individual. I dressed funny and was comfortable in my own skin. I don’t know. I never did ask him why.”

Pratt waited tables and took classes at a local community college, including a theater course. “I did a scene—something I wrote—and the teacher took me aside and said, ‘You should think about doing this professionally.’ He saw something.”

Pratt didn’t finish a full year. “It felt exactly like high school except I had to pay for it,” he explained, “and, for a kid living hand to mouth, that didn’t make sense. So I got a job as a salesman going door-to-door.”

Wait. What?

“Yeah, I saw an ad in the newspaper.”

The ad went something like: Do you dig rock ‘n’ roll and making money?

Of course, the answer to both questions was yes.

Flair For The Dramatic

Pratt was arranging wild boar on a tray and sliding it into the oven as he talked. “Hey, dude, does 300 degrees sound right to you?”

I told him it sounded low. Everything in my house goes in at least 350. He called his brother-in-law, the one who knows everything, to check. “You know what would make a great end to this story?” said Pratt, laughing. “If we ended up in the hospital with food poisoning.”

I asked about that sales job.

“I was selling coupons for things like oil changes or trips to a spa,” said Pratt, who told me it didn’t really matter what he was selling because a salesman only has one product: himself. “I was great at that,” he said. He got absorbed in this new gig, walking through town, making the same pitch again and again. It turned out to be perfect training for a future life of audition and rejection. “That’s why I believe in God and the divine,” he told me. “I feel like it was perfectly planned. People talk about rejection in Hollywood. I’m like, ‘You’re outta your f**in’ mind. Did you ever have someone sic their dog on you at an audition?” ’

If you sold enough coupons, you got to run an office somewhere in the country—you’d become a manager, in other words, moving pieces around the board. That was the carrot Pratt was chasing. It took 15 months, but he finally got it. Given charge of an office outside Denver, he left Lake Stevens in the way of a kid leaving home to meet his destiny. What a strange interlude for a leading man: this drab complex outside this strange city, salesmen fighting over the Glengarry leads. “We rented an apartment,” Pratt told me. “I slept on the balcony. And partied. I wasn’t even 21.” The novelty wore off as the truth became plain. He’d been caught in someone else’s moneymaking scheme. As the old wisdom advises, when you sit at the poker table, look for the sucker. If you can’t identify him, leave—it’s you. Pratt called his boss one morning. “ ‘This is too much for me,’ “ he said. “ ‘I’m more in debt every month. I’m so depressed. I can’t do it.’ And she said, ‘I just want you to know, Chris, that there is nothing else out there.’ “

Pratt’s mother sent him a ticket. Two years had gone by, and he was back in Lake Stevens, exactly where he’d started. Left on his own, he might have followed the classic trajectory—hero at 18, relic by 45.

So what happened?

“I was rescued.” As he said this, he stuck a fork in the oven and came at me with a piece of meat.

“Try this and tell me the truth. We can always drive down to Soho House and eat there.”

I chewed slowly.

He said it again. “Tell me the truth.”

I did not want to tell him the truth—because I liked him and did not want to go to Soho House. If I did tell the truth, I’d have said, “It tastes like burning.” Instead I said, “Good!”

He closed the oven, went on. “One of my best friends heard I’d been floundering. I had everyone convinced I’d been off doing this great sales job and making money, and I wasn’t. I had no prospects, no job, was still sort of riding the glory of high school. He saw that and bought me a ticket to Hawaii, where he’d been living.”

Pratt remembers what it was like when he first got to the island, the green hills and blue sea, how all that beauty contrasted with his mood. “My friends picked me up in a van. They had a cooler of beer. But I was not in a great place.”

Pratt got a job at Bubba Gump Shrimp. For Pratt, it was like door-to-door, a kind of acting; he threw himself into entertaining tables of kids and conventioneers.

Were you good at that job?

“I was Gumper of the year,” he told me. “They gave me the award. I got my name on a plaque. It was the kind of place that . . . Did you ever see the movie Waiting . . . ? Anna’s in that movie, and she’s great. Or Office Space? Did you ever see that? You know how [Jennifer Aniston] can’t handle the f**in’ flair? Well, I was a monster with the flair.”

Pratt was living on the beach. There was a van with a couch, a tent with a blanket. On its face, it was an idyll, five or six friends, none older than 20, never out of earshot of the breakers, yet Pratt was lost, the perfection of the locale making his estrangement only more keen. Like neon in the daytime, or a blue note on a bright day.

“I was sitting outside a grocery store—we’d convinced someone to go in and buy us beer. This is Maui. And a guy named Henry came up and recognized something in me that needed to be saved. He asked what I was doing that night, and I was honest. I said, ‘My friend’s inside buying me alcohol.’ ‘You going to go party?’ he asked. ‘Yeah.’ ‘Drink and do drugs? Meet girls, fornication?’ I was like, ‘I hope so.’ I was charmed by this guy, don’t know why. He was an Asian dude, maybe Hawaiian, in his 40s. It should’ve made me nervous but didn’t. I said, ‘Why are you asking?’ He said, ‘Jesus told me to talk to you . . .’ At that moment I was like, I think I have to go with this guy. He took me to church. Over the next few days I surprised my friends by declaring that I was going to change my life.”

O.K. Let’s stop for a moment. Because this is strange and so distant from what we expect of a movie star, especially of the clever, slapdash, wise-guy variety. But everyone needs a story to make sense of their life. Even the most successful. The extreme demands explanation. For Pratt, success, so extreme it scared him, is explained by metaphysical intervention. Which caused him to take control. In that moment, he yielded. His path has been clear ever since.

The Outsider

One day, and this was the key development, Rae Dawn Chong, an actress and the daughter of the great stoner Tommy Chong—she’d reached a professional peak in 1985 when she starred opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando—walked into Bubba Gump Shrimp. “She was with her producing partner,” said Pratt. “I think they were on vacation in Kihei. I wasn’t even supposed to take a shift that day. I was always giving away my shifts because I didn’t have much overhead. I lived in a van. But it was like I had a premonition. I always wanted to go to Hollywood. I just didn’t know I was going to get there.”

Pratt approached Chong with full, flare-filled, Gumper-of-the-year charm.

He says, “I’m your server.”

She says, “I’m Rae Dawn Chong.”

He says, “You’re a movie star.”

She says, “You’re cute. Do you act?”

He says, “F**, yeah, I act. Put me in a movie.”

She asks for his phone number. He does not have a phone—he lives in a van—so gives her the number of his friend Michael Jackson (not that Michael Jackson). She leaves a message the next day, but Michael Jackson forgets about it. Then Michael Jackson remembers. He tells Pratt, “Dawn or some Chinese chick or something . . . you got a message.”

Pratt picked up the script from Chong. It was a comedy called Cursed Part 3. There were no Parts 1 and 2. It was a film about a film crew being haunted while making a film about a haunting.

Chong stopped Pratt halfway through his audition.

She said, “We’re going to use you.”

Did you get a big part?

“Yeah,” he said, “I was the lead.”

When Pratt learned the movie would be shot in L.A., he told Chong he’d have to bow out. He couldn’t afford a plane ticket. “I had 60 bucks,” he told me. “And she was like, ‘Sweetie, we’ll fly you there.’ ”

The movie took 10 days to shoot and was never released. When I asked Pratt to describe it, he hemmed and hawed, searching for the words, washing his hands in the sink as he did so, then, in the way of a person who’s decided, F** it, I’ll just tell the truth, said, “It was the worst movie I’d ever seen.”

So what was its historical function?

It got Pratt a screen credit and a manager and a reel. It got him into the game. “The whole reason that movie came along was just so I could be brought to Hollywood.”

What did you look like back then?

Because Pratt became known as a lovable chub in the office down the hall, I was curious about how he was first presented. “I looked exactly like Heath Ledger,” he said. “I had long blond hair, still bleached out, Hawaiian . . . That’s what people were always saying: Man, you look just like Heath Ledger. Then I saw Heath Ledger on the cover of Vanity Fair, and I thought, Hey, I do look just like that guy.”

I asked Pratt what life was like in Los Angeles in those first years. He talked about living cheaply, waiting tables, taking small roles in big movies and big roles in small movies. (He met his wife while playing her love interest in Take Me Home Tonight, circa 2007.) “I was an outsider, no connections, no nepotism, nothing, a complete foreigner to Hollywood.”

The breakthrough came with Everwood, in 2002, which Pratt describes as “a single-camera, dramatic show for the WB. It went four seasons and was absolutely life-changing. That’s when I became an actor, and that was the first time I’d ever got into money, real money.”

Most people probably got to know Pratt as Andy Dwyer on Parks and Recreation. It was supposed to be a one-episode deal, but the character took off. Pratt gained weight while shooting the first season—partly because he thought it worked for the character, partly because he’d just been married and people tend to fatten up in those first, blissful years. He did not consider the downside—other than lethargy and trouble breathing—until he auditioned to play Oakland A’s first-baseman and catcher Scott Hatteberg in 2011’s Moneyball. “That was the first time I heard someone say, ‘We’re not gonna cast you—you’re too fat.’ So I decided to drop the weight, like in wrestling. I couldn’t afford a trainer, so it was all running and crash-dieting and cutting alcohol.”

Pratt had always wanted to play an action hero but did not think he could pull it off.

What changed your mind?

“Zero Dark Thirty,” he said. “That’s the first time I bulked up, got into great shape because I was playing a navy SEAL.”

Nervous when he sat down to watch the film, he came away with a new view of himself. “I was like, I buy that guy,” he said. “I’m SEAL Team Six in that movie, and I felt like it was real. I can do this. I can play those roles.

“Guardians had come around, and I passed,” Pratt said. “James Gunn [the director] passed on me, too. When they announced it, I looked it up and saw a list of the top 20 dudes in Hollywood who might play Peter Quill. I was not on that list. I did not want to go in and embarrass myself. My agent said, ‘Guardians is everything you’ve been saying you want to do.’ I said, ‘F**, you’re right.’ But I’m going to go in there and do exactly what I mean by action comedy. My brand of stuff. Brash. Honest. I played the room. Jim Gunn, the way he tells it is like this: ‘Who do we have next? Chris Pratt? What the f**? I said we weren’t going to audition the chubby guy from Parks and Rec.’ ‘Well, he’s already here.’ They’d tested probably 10 people, spent a lot of money, and James wasn’t convinced on anyone yet. When I finished [my scene], he said, ‘Do you have any questions?’ I was like, ‘Are you f**in’ crazy? Tell me everything.’ I gave him my Peter Quill version of an answer. Once you get smart about auditioning, you learn to audition before they say ‘Action.’ You walk into the room as the character. You let them think the person you are is close to the character they want. You make them think you already are that guy. Gunn was like, ‘Damn, this is it.’”

Pratt was alone when he saw the movie the first time, in a theater rented for that purpose. “When it started, I was like, This is f**in’ awesome! Then I saw the first scene of myself dancing and kicking rats, and I was like, Oh, disaster. This movie is gonna suck. I was just so hypercritical of myself. Then the next scene comes on and you see Rocket and Groot, and I was like, Wait a minute—this movie might be really f**in’ good.”

That movie changed everything for Pratt. In a moment, he went from that to this. “I made a genre jump,” he said, “a category jump, some kind of jump.”

He cemented this image in Jurassic World, in which he not only played the Harrison Ford-type role but played it in a Steven Spielberg property.

When I asked Pratt why he did Passengers, he said, “It’s the best script I’ve ever read.”

A Country Boy Can Survive

Pratt set the table as he talked. Tacos, rice, peppers. He called his son and the nanny in to eat

Just before we sat to eat, he got on his knees and had the rest of us get on our knees, and we held hands, and he thanked God for the food and the life, and he even put in a word for the Cubs. At the end of the meal, he poured shots of tequila. He’d been given a case after Jurassic World. I noticed a guitar on the wall. When I asked about it, Pratt said, “Let me show you the good guitars.” He went upstairs and came back with two acoustics—a Taylor and a beautiful Gibson, which he’d played while guest-hosting Saturday Night Live, in 2014. He picked it up and began to sing “Lady,” a Kenny Rogers hit just as cheesy as AM radio. Then we played together—“Up on Cripple Creek” and the Hank Williams Jr. tune “A Country Boy Can Survive.” He strummed a few chords, then talked about a guest appearance he’d recently made on his wife’s CBS sitcom, Mom. He’d learned the Kenny Rogers tune so he could sing it on that show. “I played it, then we kissed,” he told me. “Normally, when you do a kissing scene, it’s awkward, and when it’s done you say, ‘Are you O.K.?’ But this was different. After they yelled ‘Cut,’ we laughed and just kept on kissing.”