The golden-locked God of Thunder from Down Under speaks softly off the set but wields a big stick on it— in Thor: The Dark World, in Rush, and in a series of notable dramatic roles. Is this the moment when the 30-year-old Aussie’s blond ambition pays off?

THERE’S A BEACH ON BALI CALLED DREAMLAND.

That’s the actual name. High above it, on the glass-fronted terrace of a cliff-side villa cantilevered over the postcard-blue eternity of the Indian Ocean, Chris Hemsworth and I are picking at a platter of cut melon and pineapple, talking about how we got here.

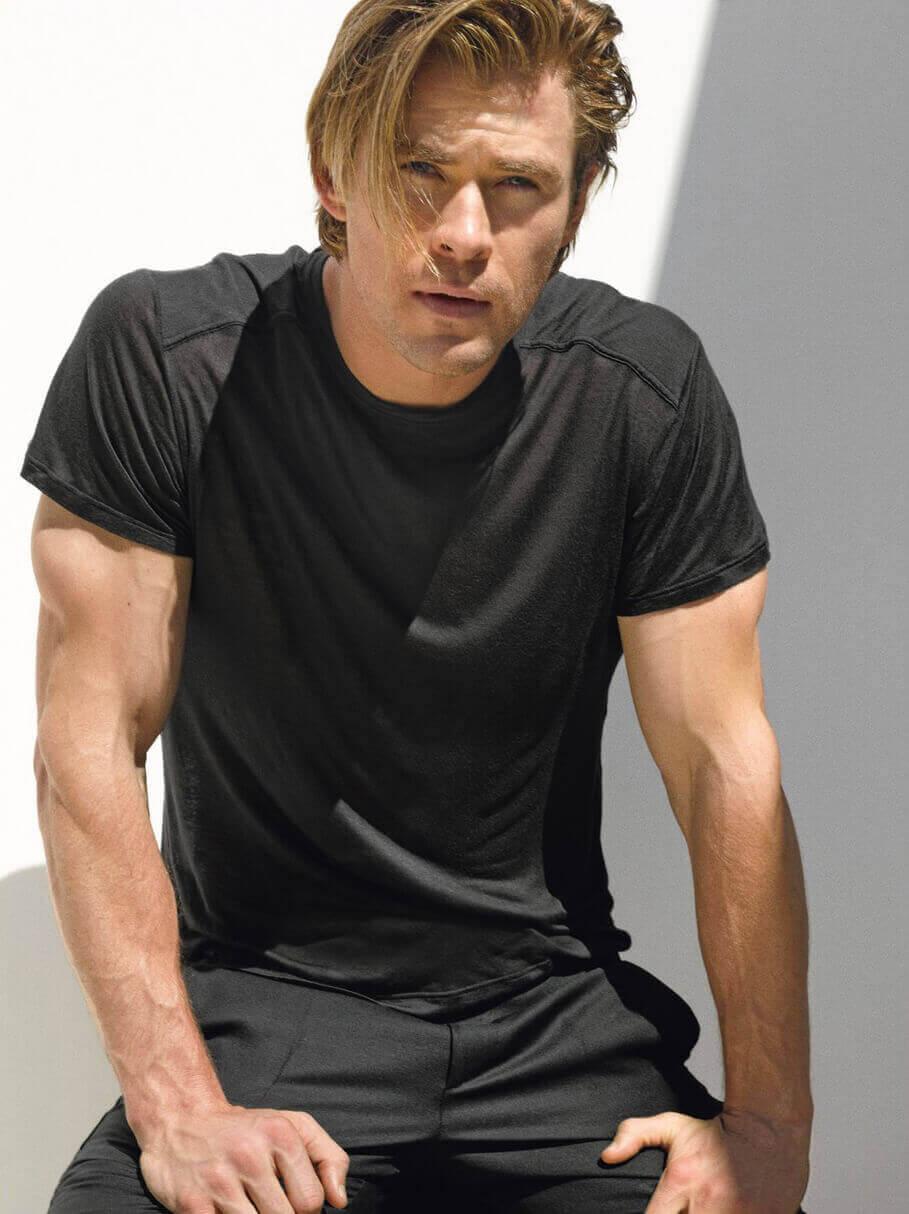

Playing the part of Thor — Hemsworth appears charmingly oversize. Offscreen, the Australian actor is approachably human-scaled. Hair pulled back, tank-topped, offering fruit.

“Sorry you had to come all this way, dude,” Hemsworth says, squinting into paradise.

I arrived in Jakarta some unknown number of days ago, demented by jet lag and 10,000 miles in coach.

A message was waiting for me on arrival: Hemsworth wasn’t in Jakarta anymore. He had been here the previous day, shooting a Michael Mann thriller about cybercrime. But it’s Hemsworth’s birthday, his 30th, and he’s unexpectedly — though sensibly enough, it seems to me — decamped to Bali for a surfing holiday with his wife, their young daughter, and some old pals.

…before very long, I was on an Air Garuda flight to crash the actor’s Balinese birthday party in Dreamland.

Hemsworth’s journey, by contrast, seems somehow more direct — and all the more remarkable for the abrupt and frictionless speed of his arrival on the scene.

Six years ago, the guy was treading water, playing waiter-slash-lifeguard Kim Hyde on the venerable Aussie soap opera Home and Away. “We shot 20 scenes a day, five shows a week,” Hemsworth says of the series that would serve as his lucky break, his acting school, and his personal crucible of endurance.

“Three and a half years playing the same character can be sort of mind-numbing,” Hemsworth says with a wincing grin. “My character was in a fire, a cyclone, a helicopter crash, a plane crash. I was hoping for a big, dramatic death.”

No such luck. Finally, Hemsworth decided he’d had enough. When his contract was up, he left the show and, in mid-2007, headed to Los Angeles to write the first chapter of his unlikely ascent. It didn’t take long. He landed a small but highly visible role as Captain Kirk’s father in J.J. Abrams’ 2009 Star Trek reboot. A brief and brooding sophomore slump followed, during which Hemsworth feared he’d peaked early and would be forced to move back home. He didn’t have to worry for long. He soon caught the eye of Joss Whedon and was cast in The Cabin in the Woods, which Whedon produced and cowrote. During that shoot, Whedon put in a good word with Kenneth Branagh, who was then searching for a Thor to carry his big-budget-action-movie debut. Hemsworth beat out the competition, including his younger brother Liam, and the rest is Asgardian history. He joined the superhero menagerie in Disney/Marvel’s megaprofitable (and Whedon-helmed) Avengers series. This month Hemsworth returns in Thor: The Dark World, alongside Tom Hiddleston, Natalie Portman, and Anthony Hopkins.

Portman, reprising her role as the God of Thunder’s love interest, says “there’s no pretension” when it comes to Hemsworth. “He’s like a person you actually want to hang out with,” she says.

(Portman adds that she’d like to see him stretch out and do a comedy: “When we were doing the first Thor, we would joke that we should remake The Way We Were. Little Jewish girl, a smoking-hot Gentile. If we work together again, that’s clearly our project.”)

Hemsworth’s once and future costar Chris Evans says that he loves the guy but hasn’t seen much of his buddy lately: “He’s a father now, and I don’t think he’s stopped working for more than a weekend since we wrapped Avengers.”

So the guy is likable, hardworking, talented, and lucky: That’s his friends’ and coworkers’ theory, and they’re sticking to it.

Still, Hemsworth admits that there’s something a little jarring about this jump cut — from unknown hunky surfer kid to lead of sequel-spawning Hollywood franchises, from a freewheeling youth spent ranging shoeless across a buffalo station in remotest Northern Territory to lounging on the terrace of this rented luxury villa, the bona fide, bankable movie star in repose.

“I paid my way in,” the actor deadpans. “My family’s in the Mafia. A couple of threats and bunch of cash goes a long way.”

All joking aside, he’s sympathetic to the line of inquiry. Six years is not exactly overnight, but neither is it anybody’s idea of a protracted apprenticeship.

“Maybe I’m asking myself the same question you’re asking,” Hemsworth offers a little hesitantly. “I’ve worked my ass off over the years, but I can’t help but see that, relatively speaking, it all has been rather quick.”

For all his time spent riding the mirthless merry-go-round of press conferences, red-carpet interviews, and the TV chat circuit, Hemsworth is refreshingly allergic to self-analysis. “It’s funny,” he says on the subject of himself. “No other job forces you to think about yourself this much. That’s a scary thing, because before you know it, it’s all pointed inward. You’re taught to think, ‘Okay, what do I want out of this scene? How am I feeling here?’ Then it’s like, ‘Awww, f** off, I.’ You start to hate I!”

But Hemsworth understands that box-office success requires a measure of disclosure, a certain tithing of the private self to the nosy moviegoing public. “The biggest thing is, you worry about being boring,” he says, looking for a way to talk about himself without sounding conceited or falsely modest or unaware of the strange allure of celebrity (he is none of these things).

It’s not just birthday-crashing writer types who push Hemsworth to overshare. “I worked with plenty of directors who are like, ‘Yeah, but what’s in there? Tell me about that time . . .’ And I’m like, ‘Listen, there is something in there, but I ain’t gonna tell you and exploit it.’ I hold that stuff pretty close. We all like the drama of the wildest personalities, but I’m not going to invent something to wallow in just to make me sound interesting.”

Pressed to explain his swift rise to the top, Hemsworth points to a certain bullheaded desire to win that’s driven him since he was a kid, the middle of three brothers in an active, competitive family. “My dad talks about the times when we’d play backyard cricket: If I got bowled out, I’d just refuse to let go of the bat and swing it at anyone who tried to take it away from me,” Hemsworth recalls. “I like to think that’s been tempered a bit over the years.”

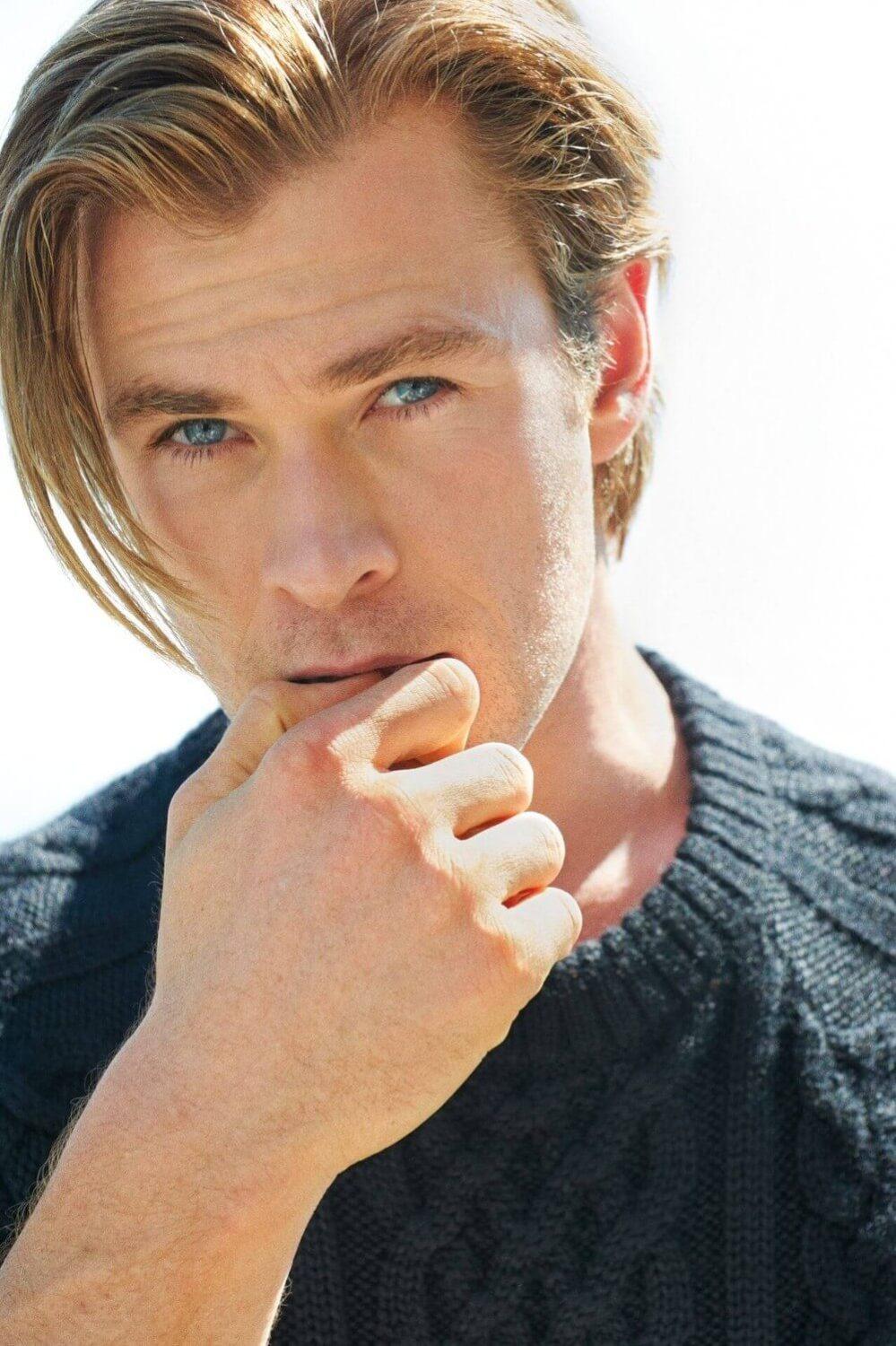

Portman says: “He’s confident in a very quiet way. He’s like the silent guy at the table. He can sit there and listen and be generous and not have to be tap-dancing all the time—which is really unusual for an actor.”

And A-list directors have begun to take notice of Hemsworth’s quieter side. Most immediately, there’s the Michael Mann cybercrime film he’s been shooting in Jakarta (and Los Angeles and Hong Kong before that). “This is a little stiller than I’ve been before,” Hemsworth says of his role as a brainy hacker.

Later, when I’m back home, Mann will call from Malaysia, where he’s two days away from finishing the exhausting shoot for his as-yet-untitled thriller. “Four countries, 71 locations, 66 days,” Mann says. His message is that hiring Hemsworth as a computer genius was not casting against type: “It would be a mistake to typecast Chris in any way. He can do anything he decides he wants to do—he has that much command over his abilities and career.

“He’s a real solid citizen,” Mann adds, laughing. “I don’t mean he’s registered to vote. I mean he’s there, you know? If we need to shoot something over again, he’s there. He’s got a great sense of responsibility and an integrity as a man that I immediately respond to and respect. He’s a smart guy, and he really can do just about anything.”

Hemsworth, for his part, wasn’t so sure he could handle one of the things Mann asked him to do to prepare for the role. This time it wasn’t learning a new martial-arts discipline. Or bulking up through overeating and overtraining. Or learning to perform against a green screen. It was worse. Much worse: nerd camp.

“I did two months of computer lessons before we started shooting,” he says. “This computer teacher with a Ph.D. from UCLA would come into this little room and give me lessons in Unix commands and whatnot. It was exciting the first day or two, then I was like, ‘Oh no, this is why I didn’t take a desk job.’ Drank more coffee than I’d ever had in my life, because it was literally putting me to sleep.”

Hemsworth shakes his head under the Balinese sun in remembered disbelief. A friend ambles over to the terrace and replaces our depleted fruit plate with a couple of cold bottles of Bintang. The weekend’s almost over, and it’s agreed they’d better finish the cases of beer they brought in.

“I think I enjoyed sword fighting more than computer lessons,” he says.

The nerd training eventually paid off. “I learned to type, for one,” Hemsworth says. “I can’t say I can hack into your Swiss bank account, but I can pretend to. There’s an intelligence to this character that’s certainly beyond my intelligence and some of the characters I’ve played before. They can make me smarter in the editing.”

• • •

“These days, even 5-year-olds will look at something and say, ‘Ah, the CGI’s crap—I’m not watching this.'”

We’re talking about the pitfalls of performing opposite a green screen rather than other actors. Hemsworth says he tries not to think too much about what kind of films he should be saying yes to. But once he did try a character-driven role, he thought: “Oh, what a relief.”

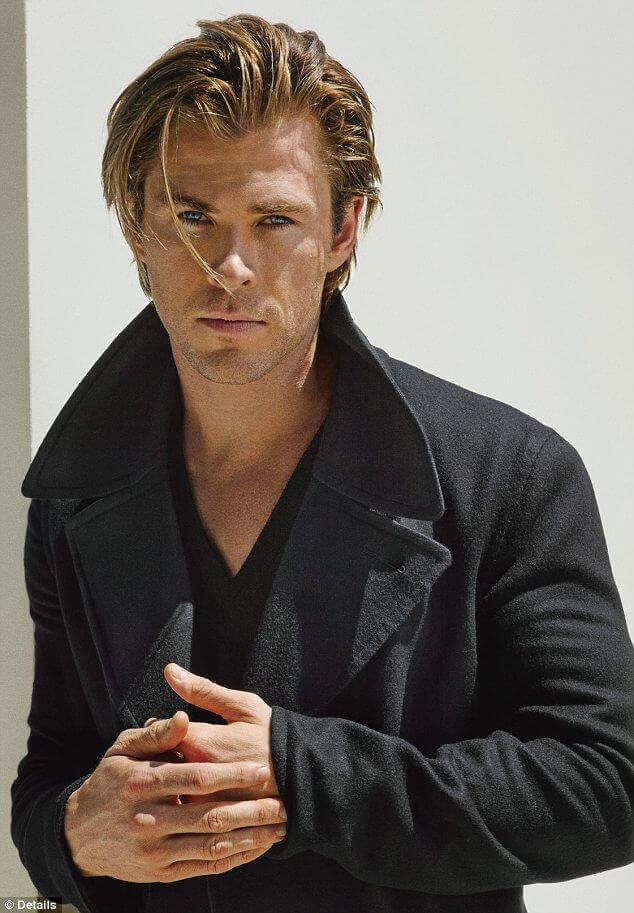

That first encounter with an actory, talky, thinky role came in the form of the real-life seventies-era British Formula One champ James Hunt in Ron Howard’s Rush. Channeling the persona of a shite-talking, lady-killing Alfie-on-wheels with predictably enviable hair might not seem like a stretch for the hunky Hemsworth. But beneath the engine roar, the film is a psychological study of the competitive spirit.

“Chris’ high-profile performances have been so focused on the physical, the way he moved,” Howard says. “But he sent me this fantastic, very raw audition tape he made in his motel room. He was wearing a T-shirt, and his hair was loose, and he had that body language. Chris is a surfer, and James Hunt exuded a kind of California quality, but with a British public-school education—”

“And great hair,” I say, interrupting.

“And great hair!” Howard goes on. “He killed it in this little audition, including the accent. And the writer, Peter Morgan, and I just looked at each other and said, ‘Okay, now we got Hunt.’ We stopped searching. It was pretty incredible.”

Howard was impressed enough with Hemsworth on set that the two are collaborating again for the director’s next project, In the Heart of the Sea, which tracks the true-story misfortunes of the whale ship Essex, upon which Melville based Moby Dick.

And Howard is unequivocal about where he sees Hemsworth’s post-action-hero roles propelling him: “It’s a little bit like when you saw Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones and then you saw him in Witness. I think he’s going to earn people’s understanding and respect in those kinds of ways, and I hope that Rush is the beginning of that.”

Hemsworth relished the change of pace and the new challenges. “It was incredibly satisfying to be on a much more intimate set, focused on the truth of a scene, as opposed to ‘Now swing on a wire and smash the bad guy with your ax,'” he says. “The fear, the newness,” Hemsworth continues, snapping his fingers excitedly, “is what keeps you on your game.”

We’ve relocated a few miles down the beach to a little surf bar that overlooks a famous point break. Hemsworth jokes about trying to figure out what to do with a visiting journalist in this idyllic place of refuge for him. His publicist suggested a hike.

“A hike?” he says in mock horror. “What is it, a date? Are we supposed to make out at the end of it?”

Of course, no one notices the actor because everyone on this beach is tall, blond, and Australian. Hemsworth talks about coming to the beaches of Padang Padang as a kid. When he and Pataky decided to marry in 2010 after knowing each other for less than a year (the guy moves fast), they chose Sumba, a couple of islands over, and tied the knot . . . when?

“Uh, I should know the answer to this. There’s a bit of a dispute . . .”

Long story somewhat shortened: A little group of friends and family descended on Sumba, and it was such a laid-back couple of weeks that no one can agree on when the actual ceremony took place. The ring his wife gave him is engraved with a date, but Hemsworth is pretty sure it was a couple of days later. “So yeah, answer about the date of my wedding: somewhere in December.”

I ask Hemsworth whether he’s reached a point where he can step back and see the arc of his career as the great, unlikely success it is. He knows he’s lucky and doesn’t want to sound ungrateful.

“There’s a brief payout, and then the bar shifts again,” he says, hesitating a bit. “I think that’s human nature. It keeps you moving forward, but it needs to be tempered a bit, too. I’ve been working solidly for a couple of years now, to the point where I have to slow down and spend some time with my family.”

Even now he worries that if he takes his foot off the pedal, in six months maybe no one will be calling. “You spend so long having your hand up, saying, ‘C’mon, c’mon—pick me!,’ there’s a fear of saying no to things. It’s bred into you. I get sh* sent to me and I think, ‘I should probably just take this.’ But now I try to say, ‘Hold on—do you even like it?’ I do have a little control now. That’s the transition—I’m not at the mercy of someone else so much.”

Hemsworth adds with a laugh, “And that is just as scary as it is liberating.”

His wife and daughter and pals are back at the villa packing up, and I’m starting to feel a bit guilty about occupying the prime afternoon hours of a rare weekend break. It’s almost time for Hemsworth to fly back to the set in Jakarta, time to leave Dreamland for a few months of constant, grueling work.

I ask him about the fear. Is it really something he feels even now, when he’s here, on the cusp or the apex or the summit or whatever it is you call getting exactly what you’ve always wanted—with all the plaudits and possibilities and perils that come with it?

“Of course,” he says. “The fear is: ‘Am I gonna be found out? Am I any good?’ The preparation is something I do obsessively, because the fear of being caught out is the worst for me.”

But there’s more to it. Hemsworth’s also afraid he won’t be found out, that all the hard work he puts in is entirely unnecessary, and that he has something of a charmed existence. He’s trying to listen to friends who tell him to relax and take more weekends like this, minus my intrusion. “But I’m like, ‘No, no, no.’ The fear is: Why did it happen so quickly? Then you go, ‘What’s the catch?'”