Pitt talks about dreams, self-doubt, and the serious work it took to become an actor he could be proud of.

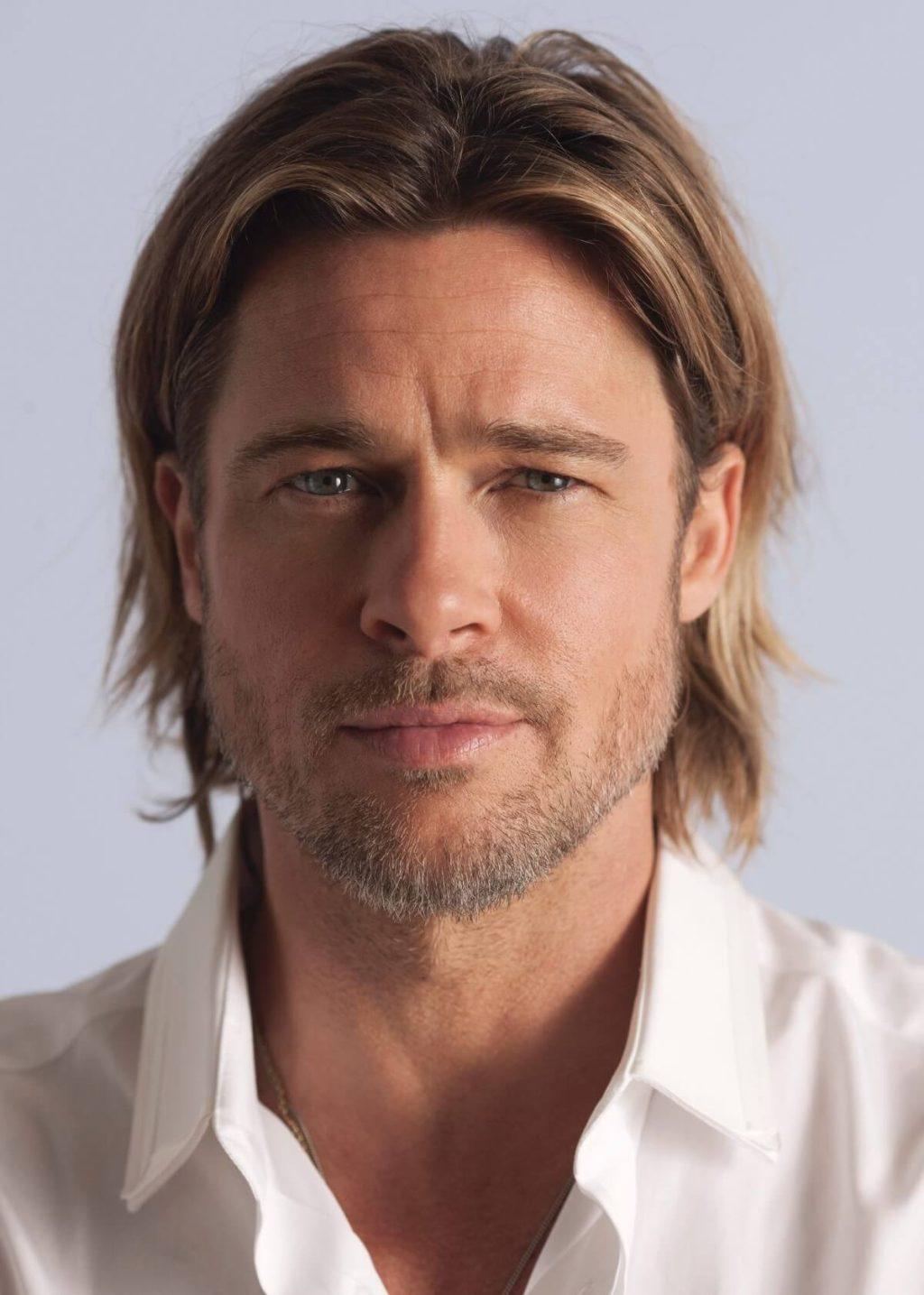

“Once I had a meeting with Quentin Tarantino where we went through five bottles of wine,” Brad Pitt says, deep into a conversation that will span three and a half hours at a London photo studio. Pitt smiles, then makes a playful stab at a guilt trip: “My kids are just waiting for me at home. I’m their father. They’re wondering, ‘When’s Daddy coming home?”‘ I tell Pitt that his kids will be fine — they’ve got a strong mother figure. He laughs and beams proudly: “Yes, they do!” In person, as in Moneyball, the actor is in terrific form. He’s intrigued by the prospect of really reflecting on his entire career for the first time and, in general, seems happy and focused — not to mention unfailingly gracious — in a way that could not be plausibly faked, even by an actor as good as the one he has become.

I first interviewed you in 1992, when you were 28 and shooting Kalifornia. You were totally charming, but you were so evasive about everything that at one point I actually moved my dinner plate and began beating my head against the table.

[Laughs] Where I grew up — we started out in Oklahoma and then moved to Missouri — it was considered hubris to talk about yourself. And the downside of that was that ideas rarely got exchanged, or true feelings. That’s why I was cagey at the time. When I was starting out, it took me 10 years to get semi-comfortable with this whole exchange.

Your first starring role was in a movie that I’ve never even heard of, Dark Side of the Sun. It was shelved because of the revolution in Croatia, then released in 1997.

I don’t think it was shelved because of that. I think it was shelved because it was lacking in entertainment value.

You had been doing TV stuff.

Yeah, but minor things. I was in acting class. I was still doing extra work. You know, when I first started, they were trying to get me into sitcoms — I think because I had that kind of Wonder Bread look and my hair always went into place. I kept saying, “I’m not good at sitcoms. I don’t know how to do that.”

You did a pretty great cameo on Friends. Don’t be so hard on yourself.

But that was a little bit later, and I like those guys. They’re a great bunch of guys.

So, early on, you wanted to show people what you could really do.

Yeah. The movies I loved were a complete 180 from situation comedy, and that’s what I wanted to head towards.

Your first role that really knocked everybody out was in Thelma & Louise.

Great part. I was really lucky to get that. I don’t remember much other than: I knew what it was — I knew it was that entry — and I thought I knew what I could do with it. I’m going to go in and do my thing, and nothing will shake me. I remember being dead set on that.

Did it change your life?

A little bit. More opportunities started coming, but you didn’t get people chasing you with cameras and trying to look through your windows.

In 1992, you had a starring role in A River Runs Through It.

That was a big deal. I grew up on Redford films and Newman films and Clint Eastwood and a lot of the Westerns. It was a beautiful story and one I understood because of how I grew up.

Many people pointed out how much you looked like Redford in the movie, which must have been irritating on some level.

It’s hugely complimentary because I think he’s one of the greats — and actually underrated as an actor — but you want to find your own thing. You want to stake your own claim. You don’t want to be called a copycat.

You’ve been critical of your performance in River. It’s a good, solid movie, though.

Robert Redford made a quality movie. But I don’t think I was skilled enough. I think I could have done better. Maybe it was the pressure of the part, and playing someone who was a real person — and the family was around occasionally — and not wanting to let Redford down. But again, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen it. I was much more critical then. I was more self-conscious, you know?

With Kalifornia, your chipped front tooth was real, right?

Yeah, I chipped it when I was in fourth grade or something. I was sick. You know: big fever and delirious dreams. I passed out in the bathroom, woke up, and the tooth was chipped. But Kalifornia — that was one where I got to mess it up and get dirty. The writer was actually really pissed off at me. He wrote more of a Badlands kind of character.

That movie was the first time you really messed with audiences’ expectations.

I remember another movie star speaking with me about a particular project, and he said, “My audience would never allow me to do that.” It’s like cymbals went off: I don’t ever want to be shackled by that.

You had a great little role in True Romance in 1993, as the couch potato, Floyd.

I had met Tony Scott and really liked him. We talked about some of the other characters in it, and I said, “I don’t think they’re for me. But there’s one guy I like in it. It’s the guy that’s so irresponsible that he gets everyone else killed.” And he said, “Great, do it.” Then I called him up a couple nights before, and I said, “Can I make him a stoner?” And he said, “Yes.”

Okay, Interview With the Vampire. You look miserable in the movie.

I am miserable. Six months in the f**ing dark.

There was also the makeup, the contact lenses…

Contact lenses, makeup, I’m playing the b*ch role…

Well, you must have known going into it what the role was.

No, I didn’t. There was no script. I knew the book, and in the book you have this guy asking, “Who am I?” Which was probably applicable to me at that time. “Am I good? Am I of the angels? Am I bad? Am I of the devil?” In the book it is a guy going on this search of discovery. And in the meantime, he has this Lestat character that he’s entranced by and abhors. But then I got the script two weeks before we started shooting.

Didn’t you read earlier drafts? You must have.

No, I didn’t.

Let me tell you something, once you’re a movie star, you can ask to see the script.

I know, but I wasn’t then, and you learn. By the way, Neil Jordan is a really good friend of mine. We’ve talked about all this, which is the only reason I talk about it now. In the movie, they took the sensational aspects of Lestat and made that the pulse of the film, and those things are very enjoyable and very good, but for me, there was just nothing to do — you just sit and watch.

So it turned into a Tom Cruise vehicle, essentially?

Yeah, and no discredit to Tom, man. He had pressure on him. There were all the fanboys of the book. He had all this pressure to make it work, and he made it work — and good on him.

But you were stuck with a passive role.

Now I’d be able to say, “This is a problem. I’m out of here, or we fix this.” But the great thing that came out of that movie is that it birthed my love affair with New Orleans. We were shooting nights. So I just rode my bike around all night. I made some great friends there. But then we get to London, and London was f**ing dark. London was dead of winter. We’re shooting in Pinewood, which is an old institution — all the James Bond films. There’s no windows in there. It hasn’t been refabbed in decades. You leave for work in the dark — you go into this cauldron, this mausoleum — and then you come out and it’s dark. I’m telling you, one day it broke me. It was like, life’s too short for this quality of life. I called David Geffen, who was a good friend. He was a producer, and he’d just come to visit. I said, “David, I can’t do this anymore. I can’t do it. What will it cost me to get out?” And he goes, very calmly, “Forty million dollars.” And I go, “Okay, thank you.” It actually took the anxiety off of me. I was like, “I’ve got to man up and ride this through, and that’s what I’m going to do.”

Maybe you should have haggled and offered him 10 million.

No, I didn’t have 10. I had, like, 10 bucks, you know?

Oh, come on.

No, no, no. I had nothing, man. I didn’t have a house.

How is that possible?

I’d just done Legends…

Hey, don’t go rushing ahead to Legends.

[Laughs] But you jumped — you jumped to Interview.

You know what? I’m in charge here. Legends actually came out after Interview — you just shot them in a different order. Last question on Interview before we move on: You played a vampire before there were 30 billion modern takes on them, like Twilight. What do you think about our crazy vampire culture?

I don’t know enough about it, really. Listen, because of my kids, I see only movies for 10 and under. I’ve seen them all, and I’ve seen them 10 times over.

So you must have seen Taylor Lautner in The Adventures of SharkBoy and LavaGirl.

SharkBoy and LavaGirl? That’s a great movie. Which one is he? SharkBoy?

Yes. And he plays the third wheel in Twilight.

The guy that’s always photographed with his shirt off — is that the guy? That’s SharkBoy? Wow. I had no idea.

Okay, Legends of the Fall. It’s pretty melodramatic, but a lot of people have a soft spot for it — particularly women, because of you and Aidan Quinn.

I really liked the story, and it speaks to my roots. But I was battling a lot of my own stuff on this one, and I took it out on [director Edward Zwick] sometimes. I don’t think I was the most delightful human being to be around. Beautiful country and beautiful sets. But I think it was only a 40-day shoot, and it rained, like, 33 out of 40 days. Having come from that area, what I was trying to impart on the piece was that these guys don’t show their feelings — much like me being cagey in those interviews.

Why weren’t you delightful to be around? I don’t see you trashing trailers.

No, I’ve never done that, but my affliction has been…I can make something or draw something or design something better than I can explain it.

You know who else is like that? All men.

According to women, you mean. No, you talk to Mike Nichols, and every sentence is a pearl of wisdom, and you go, ‘I wish I had that clarity.”

You ended up feeling like your performance in Legends was too morose.

Depression is not interesting to watch. It’s also the failure of my Vampire character. Let me just say for the record, though: Ed’s a friend of mine. We’ve had these conversations, and debated it. I learned something very valuable from that experience, and he will tell you he learned something too. I don’t lament the failures. The failures prepare you for the next one. It’s a step you needed to take, and I’m all for it.

Your next movie was—

Oh, I’ve got a story for you! Legends was the first time I ever saw a marketing report after a film had been tested, and they said we had to take out my favorite scene in the film. I said, “Why?” They said it was the most hated scene. I said, “That can’t be. I understand that it’s uncomfortable, but it’s a monumental scene. Can I see these reports?” And they showed them to me. It was also the second-most-liked scene. And I go, “Guys, this is exactly why we’re here. We want to evoke emotion — not favorable opinion, not agreement.”

Forbid you get an actual reaction from people. What was the scene?

It doesn’t matter now. It was cut.

But you liked it!

Yeah, but I had no juice.

You had juice!

No, I had no juice. But I had juice on Se7en. With Se7en, I said, “I will do it on one condition — the head stays in the box. Put in the contract that the head stays in the box.” Actually, there was a second thing, too: “He’s got to shoot the killer in the end. He doesn’t do the ‘right’ thing, he does the thing of passion.” Those two things are in the contract. Cut to: Se7en has been put together, and they’ve tested it. They go, “You know, he would be much more heroic if he didn’t shoot John Doe — and it’s too unsettling with the head in the box. We think maybe if it was the dog’s head in the box…”

You got your first Oscar nomination for playing a mental patient in 12 Monkeys.

I was starting to get some opportunities, and they were pushing me on Terry Gilliam. I’m not sure Terry was convinced. He seemed open to me, but I think I got force-fed to him.

Did you feel unwelcome on the set?

No, we were rocking from day one. For that film, I locked myself into an apartment in Philly. I went out maybe three times in two weeks. I’m watching Titicut Follies, this documentary [about a hospital for the criminally insane]. I’m watching anything from Dennis Hopper. I’m trying to find the voice and the move. I’m bouncing off the walls. In truth, I nailed the first half of that movie, and I dogged the second half. I rode the gimmick. I rode the manic. That’s what’s wrong with it. A year and a half later, I woke up in the middle of the night and went, “That’s what it was.” I played it all manic, and that was a mistake.

Ironically you were named Sexiest Man Alive around the time you were playing this disturbing character. How’d that feel?

I was really uncomfortable. What does it mean? What are you talking about? What are we doing here?

“How am I going to hit on women if I’ve got to live up to that?”

I’ve always been mistrustful of my own hubris, and it put me on guard. Like, it was dangerous. What do they say? Don’t believe your own hype.

Actors never admit to wanting to be Sexiest Man Alive — but the dirty little secret seems to be that many of them love it.

Well, they’re not saying you’re the Biggest A–hole, you know? When you get older, you realize it’s just for fun. Clooney and I were able to have fun with it later. But in some ways, I’m still a kid from Missouri and Oklahoma and I’m trying to find my way. By the way, we’re only talking about a blip. I didn’t spend much time thinking about it.

Sleepers.

I think I was a disservice to it. This is the period where I really started getting confused and discombobulated. Because [my career] started blowing up, for one. Suddenly, I had a lot of people in my ear telling me what I should do and what I shouldn’t do.

The Devil’s Own wasn’t an easy shoot.

I really like Devil’s Own. It was a good schooling for me.

A lot of the movie was made up on the fly, right?

All of it, man. The [shoot took] seven months. It should have been three months. The experience taught me how ludicrous it could be throwing money at a problem. But I met Gordon Willis, one of the great [cinematographers], and it was my first attempt at an accent that was truly foreign to me. Still, I think the movie could have been better. Literally, the script got thrown out. Larry Gordon, the producer, is a good friend of mine. He said it to me point-blank, “I understand if you want to go away. We’re throwing the script out. Make your choice, big man. You can come with us — we’re going to figure it out as we go along — or you’re free to walk.” And I decided to stay.

Because Harrison Ford got really good pot?

[Laughs] No comment.

After Devil’s Own you made Seven Years in Tibet, about the Austrian mountain climber Heinrich Harrer.

It was such a great experience. I was beat to s* after Devil’s Own. The script for Seven Years had a prison-break scene that was like a Papillon scene, and I loved explorers and it was a quiet movie and I love the mountains.

You were in Argentina for a long time.

Six months. And I was really a shut-in at this time. I did not know how to deal with [the fame]. Argentina was a great experience, but I was lost. Really lost.

You didn’t know how to pick roles that would help you grow, you mean? Who did you trust at that point?

No one. No one. I didn’t have anyone to make me better.

So you made Meet Joe Black. Which probably didn’t help matters.

That was the pinnacle of my…loss of direction and compass.

You did get to reteam with Anthony Hopkins again, after having done Legends with him.

Mr. Hopkins is one of the greats, and really kind and giving — one of those that I take a lot of notes from. But I dogged it. I muffed it. I shouldn’t have been there in the first place. I should have been decompressing. I just didn’t crack the piece. I thought, “Maybe there’s some Being There kind of thing in this.” Someone could have done a better job in it. Because Tony didn’t dog it. Tony nailed it.

Now we come to Fight Club. It’s become a fiercely beloved cult classic, but it flopped at the box office.

I remember Fight Club played at the Venice Film Festival at a midnight screening. And Edward Norton and I, after having a few drinks, were sitting next to the president who’s running the whole thing. We’re sitting up in the balcony. It’s subtitled, and we are the only f**ers laughing. It gets to one of Helena [Bonham Carter’s] scandalous lines — “I haven’t been f**ed like that since grade school!” — and literally, the guy running the festival got up and left. Edward and I were still the only ones laughing. You could hear two idiots up in the balcony cackling through the whole thing.

You knew it was a keeper despite the reception, didn’t you?

I knew it when we were doing it. I’d had the feeling on Se7en. I had it on True Romance — that feeling when you know it’s right. So I know the feeling now. And it happened on Fight Club. By this point I can recognize when something’s happening.

After Fight Club, you did a memorable role in Guy Ritchie’s movie Snatch. You played a gypsy fighter who spoke in gibberish.

This is one of my favorites, by the way — because of the degree of difficulty. I started working on the accent, and it just wasn’t right. We were supposed to start shooting on Monday, and I said to Guy on Sunday night, “Guy, I am going to f** up your movie. I do not have it. You should do it.” Guy’s a fighter and he’s quite brawny and he does a pretty good accent. He just said, “No, mate. I’m not doing it.” So I’m really sweating it, and a friend of mine — a security guy from Ireland — kept saying, “You can never f**ing understand these [gypsies]. You can never understand what they’re saying.”

So it’s 10 o’clock at night. I’m supposed to leave at 5 o’clock in the morning, 6 to set. I start walking the streets. I’m staying in a house in north London. I just start walking the streets and chain-smoking, and it just keeps playing in my head: “You can never understand what they’re saying.” These guys were speaking code because they didn’t want other people to understand. I was reminded of Benicio Del Toro in The Usual Suspects, which was one of the genius roles. And I started walking around in circles like a crazy person, talking to myself, and I started to find this rhythm where you couldn’t really understand the words. Then it started to feel right. So I call up Guy, at maybe midnight. I woke him up and said, “I think I got something, but do you care if your dialogue is not understandable?” He said, “No, man. We’ll put in subtitles.” Literally, it was like a Hail Mary with three seconds on the clock. It’s scary when you find it at the last minute.

The Mexican was next up. You and Julia Roberts seemed like a dream team, but you were almost too famous for that movie.

We couldn’t make a little experimental fun thing because of our weight. It actually shackled the thing and started to get in the way.

You and she seem like incredibly different people to me.

I love her. She’s so articulate and witty and vivacious — everything I’m not.

Oh, I think you’re vivacious!

Thank you, darling.

You wore some great suits in Ocean’s Eleven, but of course you had to be stuffing your face with fast food to add a little spin to the role.

There was a rationale behind it: [As a thief] you’re always on the go. There’s no time to eat, so you grab what you can. It was about realism and then it started to become: Maybe he’s filling some need. So it grew into something, but it didn’t start that way.

And then you got into the best shape of your life to play Achilles in Troy.

I was turning 40. I wanted to go all out and just see what I could do. I worked for a year on that one, physically. Now I find that look very mundane. It’s just everywhere. I actually think people aging is more interesting.

You were never comfortable with all the focus on the way you look. Still, starting to age had to be a drag.

[Shakes his head] I was starting my family. To me, it’s been an amazing time. I actually feel like, “Oh, good, that’s off me.”

Speaking of which: Mr. & Mrs. Smith.

A husband and wife who actually want to kill each other — I thought that was a launching pad for something really fun and vibrant. Again, that was something we were developing as we were going along, and Angie’s a great partner in that. We work really well together. We had some good workshops beforehand. Had some good laughs and ideas. That was just a great collaboration that turned into a greater collaboration.

You and Angelina have a policy that you never work at the same time. How are you ever going to make another movie with her?

I know. We should be doing them together — that’s what we should be doing. We should be doing everything together, and then we could work less. We could have more time off.

I’m sure you feel protective of Angelina. When you’re at the Golden Globes and Ricky Gervais is making jokes about The Tourist, do you want to go up and punch him in the face?

Oh, no. He’s a comedian. Listen, man, if we’re that shallow-skinned, we shouldn’t be in here. We’re used to being in the ring and taking some punches.

Let’s talk about the last half-dozen years. You’ve made three very powerful movies that very few people saw: Babel, The Assassination of Jesse James, and The Tree of Life. I especially loved Jesse James, which made about $3 million, I believe.

Maybe $2.99999. You know, I love that film too. I find it lyrical and poetic and under the surface. No one loved it.

Do you mean the studio? Of course they didn’t love it. They made $3 million.

To their credit, they put $40 million into that movie, and they made nothing, so I understand their disdain.

And you know why they put $40 million into it — he’s sitting right here.

Yeah, I know, I know.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button had really interesting special effects. I assume you recorded your dialogue in a cozy studio and ate cheeseburgers while everybody else worked. Is that fair?

[Laughs] I worked hard, man. I worked hard.

Anyway, you got nominated for Best Actor.

For me, it goes back to [director David] Fincher. He can’t make a bad movie. Fincher and [screenwriter] Eric Roth. There’s no two other men I’d rather spend time with — as long as everyone’s clothes are on.

In 2009, you and Quentin Tarantino made Inglourious Basterds.

Quentin and I have a long history because he wrote True Romance. We kind of showed up [on the pop culture scene] at the same time, so we’ve always kind of crossed paths. And when I put the script down, I heard the character’s voice, I felt the walk. He had just written it so well.

You’ve got a great line in the woods toward the end of the movie. You’ve just executed a Nazi prisoner. Christoph Waltz barks, “You’ll be shot for this!” And you say, “Nah, I don’t think so. More like chewed out. I’ve been chewed out before.”

Well, that’s kind of my life. I remember being, like, elementary president or something and getting called to the principal’s office for doing something. Junior high, same thing. And high school, getting in a fight, getting suspended.

You became famous about the same time as not just Tarantino but also Nirvana. Looking back, I noticed that the word grunge came up a lot when people wrote about you.

[Laughs] I had a period when I was hygienically challenged. You’re fighting against the thing you’re supposed to be — that polished kind of thing.

I remember you saying once that you disliked the media’s version of Brad Pitt so much that you actually wanted to beat him up.

“I wanna go slap the s* out of him”? Probably. I have some vague recollection of that.

Tree of Life was really moving. I remember sitting in the movie theater and thinking, “What if you just walked into this from off the street and knew nothing about it?” It’s like a movie from another planet.

I gotta say, I enjoy that. It’s not conventional in any way.

There was a story in the papers about a movie theater putting up a sign to warn people that they wouldn’t get their money back if they didn’t like Tree of Life.

[Laughs] They said that? I didn’t know that. That’s great.

You didn’t intend to be in the movie. Heath Ledger was originally attached, right?

I think he had other things he was dealing with at that time and didn’t feel it was right for him, which I understand. It’s gotta be personal to you or you’re going to do it a disservice. His passing away threw me back to a dark moment on Vampire. Because we lost River [Phoenix]. Literally a week before he’s supposed to come in, he passed away. It was a horrible moment. Christian Slater came in and gallantly filled in for him. But that whole thing was dark.

Okay, we’ve arrived at the present day: Let’s talk about Moneyball.

Is that it? Is that all the movies? I’m just trying to think.

We skipped some things, but basically, yes.

Am I talking more about negative experiences than positive ones?

You’re being honest. Don’t start second-guessing yourself. I can’t handle it.

No, I’m just curious. Because I don’t look at it that way. I’ve had so many positive experiences. I feel very fortunate. I feel like I’ve learned a lot along the way. I’ve met really fascinating people. And it’s just been an inspiration, and I’m grateful for it.

Understood. I was struck by your performance in Moneyball. My first thought — and this may make you angry — was that over the years you’ve been drawn to some dark and showy stuff. Sometimes you were good, sometimes you were not so great. And here you are doing a leading role with absolutely no bells and whistles — and I’ve never believed a performance of yours more. Are you getting angry?

Not yet. Fincher said something to me. He said, “It’s amazing. You work, but you’ve done nothing that’s iconic — nothing that’s become Han Solo or Indiana Jones.” I thought about it, and I’m like, “you’re right.”

What was his point? That it’s strange that you keep getting work?

You know what? In a way, I think so!

Moneyball is about the general manager of a baseball team who has so little money to hire players that he has to upend all these entrenched ideas about who’s worth what. What’s the Hollywood corollary to that? They’re always trying to figure out how to make money without spending money.

Well, the funny thing is that I think that’s how they got the book. They had Billy Beane as a speaker because they wanted to see how they could implement the ideas of Moneyball into the Hollywood studio system, and then they end up with me doing the movie…at a discount.

Really?

To do anything that’s a labor of love, there’s always some discount.

And I can’t imagine you made a bunch of money from Tree of Life.

Yeah, and I think Jesse actually cost me money.

What drew you to Moneyball?

What I found really interesting were the underdog themes — this idea of questioning perceived notions, you know? Things you’re told as fact. Which I’m sure has something to do with my religious upbringing.

Growing up Baptist was the best thing that ever happened to you — because then you could rebel against it.

I don’t want to put it that way because…

I’m being flippant, I apologize.

See, I wrestle with that — because I speak out too much.

About religion?

I see the comfort it brings people, and I don’t want to deny anyone that. I just don’t like the separatism that comes from religion, and, without fail, the need to put your beliefs on someone else. When you start telling someone else how to live, you should check yourself, man. It drives me f**ing crazy. I’m serious.

You’re shooting the zombie movie World War Z at the moment. I just read about how you rescued an extra on the set. Congratulations on that.

I have no idea what you’re talking about.

Seriously? It was all over the Internet.

I make a point of not seeing that stuff.

An extra fell down and was going to get trampled, but you swooped in on a horse and it was very gallant.

On a horse? I haven’t been on a horse. There are no horses in the movie.

Okay, forget the horse. But you came and saved her somehow and it was very gallant.

That’s bulls*. Listen, when someone falls down, you’re going to help.

Honestly? If I were a movie star, I would send one of my assistants.

Listen, a lot of our scenes are with masses of people. We’ve had several scenes where people have fallen down.

Have you saved any lives at all?

I have not saved any lives, okay? People fall and twist ankles — the extras have really been giving it. And you don’t want people to get hurt. If I’m not the first one there, someone else is.

Not to take anything away from your rescue, but I think Kate Winslet saving Richard Branson’s mother was a little more heroic.

[Laughs] I did see that.

I was thinking about how you’ve been name-checked in at least two songs over the years. There was the old Shania Twain song: “Okay, so you’re Brad Pitt — that don’t impress me much.” Remember that one?

Unfortunately, yeah.

What’s the matter? You’d rather be in a heavy metal song?

[Laughs] Yeah. Precisely.

And last summer there was that song “Billionaire.”

Yep, yep.

Travie McCoy says that if he were a billionaire, he’d “probably pull an Angelina and Brad Pitt/And adopt a bunch of babies that ain’t never had s*.” That’s nice, no?

Yeah, that’s sweet. It’s sweet. It’s just unfortunate that my name rhymes with s*.