How, in times like these, is a golden-haired, chiseled-bodied action star supposed to be…relevant?

On field day recently at Chris Hemsworth’s daughter’s school, he and a slew of other fathers prepared for the “dads race.” They assembled—all feigning disinterest, all ready to kill for victory. The other dads had dressed to move, but Hemsworth was wearing jeans and boots. Hours before, having watched his daughter’s events—the egg-and-spoon race, the 100-meter and the 200-meter dash—he offered his 6-year-old some fatherly wisdom: “I was like, ‘It’s great, honey. It’s not about winning.’ ”

But that advice was trash, he realized. He got a bad start, pulled it together—his Thor muscles snapping to attention. The finish drew nearer until, suddenly, he was the champion. “There was just this wave of nirvana,” Hemsworth recalls. “I turn around, and I go, ‘Where’s my daughter? Where is she?’ And she’s like, ‘Dad, did you win?’ And I’m like, ‘Did I win? You didn’t see it?!’ They gave me a sticker. A first-place sticker.”

Hemsworth called his wife, Elsa Pataky. Pataky had been shooting that day, but she heard all about the Running of the Dads—repeatedly. “I’ve never seen him so excited, not even about getting a big job,” Pataky says with a laugh. “It was probably one of the best things that has happened to him in his life, which is funny, right? All the things he has achieved.”

The next day, Hemsworth had to hop a plane and fly to London to shoot his next film. He’d been home in Byron Bay, Australia, for a few months, and his daughter was distraught that he was leaving. “She’s normally like, ‘Yeah, see you, Daddy. Cool.’ She was like, ‘Papa! Papa! Papa!’ She doesn’t always call me Papa, either.” Hemsworth found the shirt he had been wearing the day before, with the first-place sticker still stuck on it, and offered it to her. “I wasn’t, like, sobbing, but…” But it shattered him.

“Obviously women are asked all the time, ‘How do you balance it?’ Men are never asked that,” Tessa Thompson, his co-star in Thor: Ragnarok, and Men in Black, tells me. Hemsworth’s frankness about his fatherly priorities is endearing, she says, because it’s effortless. “It’s so lovable, because it’s really honest.”

Back when Hemsworth was first starting out in Hollywood, it was better to be a rebel than a dad. He had appeared for a few years in the Australian soap opera Home and Away—the launchpad that also produced Naomi Watts and Heath Ledger—and arrived in America in 2007.

“I remember trying to be Colin Farrell. Thinking, ‘People love the bad boy.’ Going out and being sort of reckless. But no one cared. There wasn’t the presence of paparazzi, nor the presence of social media, nor the immediacy of all these platforms.” He’s quick to clarify that he wasn’t doing anything bad bad—“just, like, being drunk.”

Mild as they were, those days were fleeting. Hemsworth and Pataky met in Los Angeles in 2010. “He was a very mature person for his age,” recalls Pataky. “I could totally feel that he loved kids. And it’s something that just melts you, as a woman.” They married fairly quickly. Once, a publicist—not his—advised Hemsworth not to let people know too much about his personal life. “‘The more they know about you, the harder it is for people to believe your character,’” he remembers the publicist telling him. “They want to believe the fantasy that that could be them on the screen in that situation, doing whatever.”

“It was quite jarring for my family and friends when I was on-screen doing a straight, heroic, sort of overly masculine kind of thing.” More recently, filmgoers have finally gotten to see what he is. He tested those waters in 2016’s female-led Ghostbusters. And last year, he played a re-invented version of Thor —a hero suddenly less sure of himself. Hemsworth and director Taika Waititi wanted to create a Thor who could show more vulnerability—they had more Kurt Russell in mind than Clint Eastwood. “Not to say that Kurt Russell has ever been ‘less masculine’ than contemporary heroes,” Waititi explains. “[His characters were] just more flawed than contemporary heroes.”

This fall Hemsworth stars in the artsy crime thriller Bad Times at the El Royale—a film that excited him for the same reasons the last Thor movie did: It didn’t feel safe or entirely conventional. “It’s got a kind of Tarantino energy to it. It’s a thriller and a drama, but there’s some humorous moments—in an insane way. I just want to be surprised. I have a real fear of being bored.”

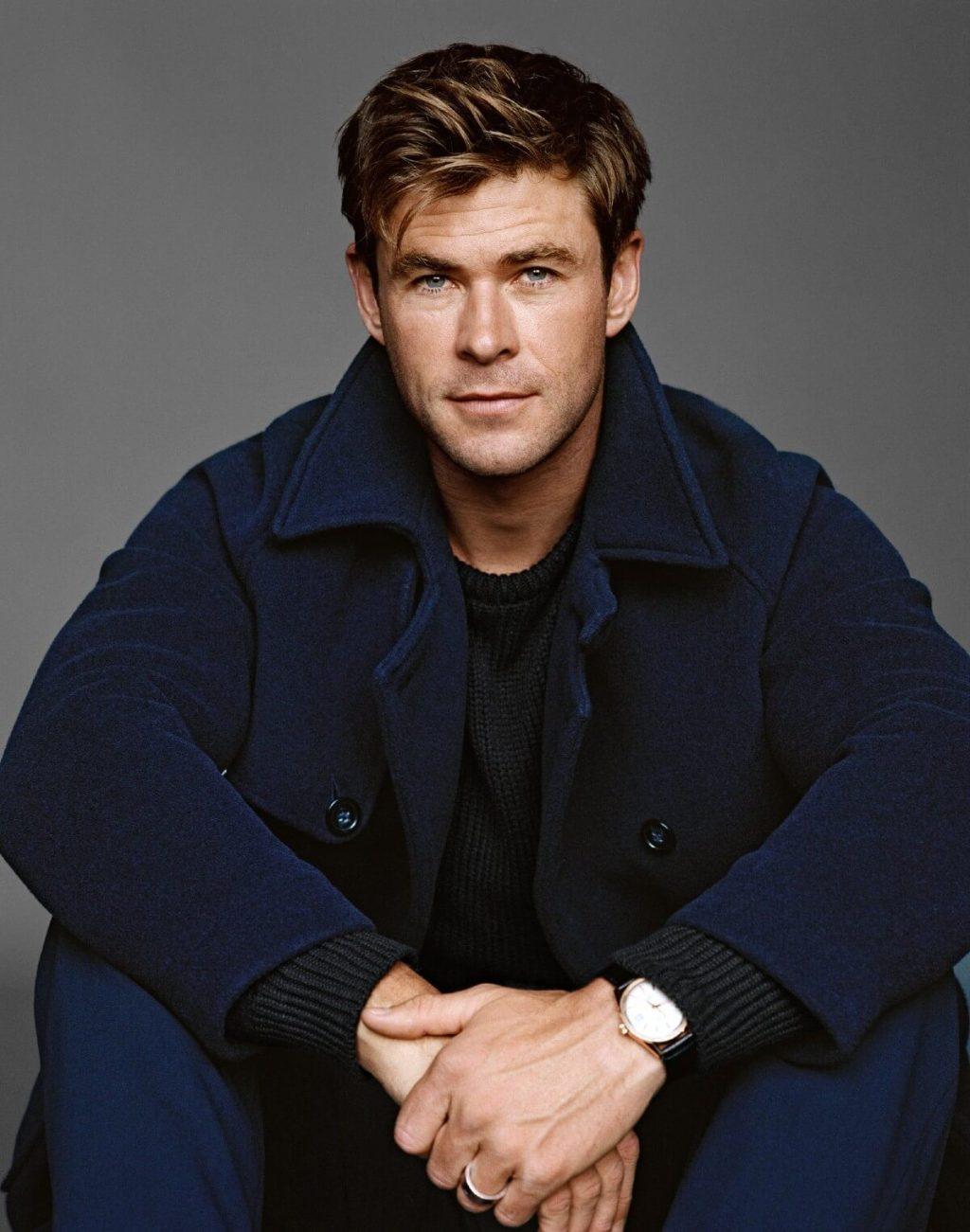

It helps still to look the part of the stereotypical star. And contrary to my assumptions about Hemsworth and about those hailing from Australia—where, it seems, everyone looks like they just crawled out of an Abercrombie catalog—it takes a lot of hard work to look like Chris Hemsworth.

Today that hard work must take place in a hotel gym in London’s Southwark neighborhood. Though this one can barely call itself a gym. It’s a single room, small and poorly appointed. The only other people here are a pair of women doing gentle cardio by the windows. And then Hemsworth and his trainer arrive.

Hemsworth has brought to London a mini entourage of friends turned employees. There’s his trainer, Luke Zocchi, who projects overwhelming goodwill even when he’s screaming about squats. And there’s Aaron Grist, Hemsworth’s assistant. Zocchi and Grist merrily mock him. When Hemsworth wonders aloud who is staying in the hotel’s penthouse, Zocchi quickly jumps in: “Guess you aren’t as famous as you thought, heh?”

They’ve all known one another since they were “this big,” and when they walk together they look like a boy band without the angst.

When he talks to non-Australians, Hemsworth reins in his accent, but when he and Zocchi get going, it’s a lot of “innits” and “mates.” Zocchi starts him off on the treadmill, where Hemsworth begins at an eye-widening incline, a punishing slant that goes up and up over the next ten minutes. For his current role in Men in Black, he doesn’t need to be Thor-fit, just normal Hemsworth-fit. The women, on the ellipticals now, glance over every so often, more annoyed than anything else.

Hemsworth barely slept the night before. He tells me this while punching the air a few times, then whipping around to walk backward. Soon he’s on to bear crawls. He can traverse the entire room in two bear crawls and one frog jump, and he’s surprisingly light-footed. “You have to move like a kid moves!”

For Hemsworth, a 30-minute circuit in his hotel is not ideal. He’d rather be on a surfboard. He favors fitness for function versus for aesthetics. “That’s the way we grew up,” he explains. Recently, Hemsworth’s brother Liam Instagrammed a photo of their parents, Leonie and Craig. His father, Craig, shirtless in the photo, is Chris, aged 10 years—15, max—with some light makeup. His dad’s physique, Hemsworth tells me, is naturally Aussie-built, not gym-groomed. “He’s always been really athletic, but I don’t think he’s ever lifted weights in his life. It’s a functional sort of strength. We had maybe a few acres of property, and we lived in a national forest, and he was always trimming trees and cutting paths in case there was a bushfire.”

Hemsworth and his brothers, Luke and Liam, grew up between Melbourne and an Aboriginal community in the bush. Craig worked as a social worker, Leonie as an English teacher. Hemsworth started acting after high school, in 2002, and scored a role on Home and Away two years later. In his mind, he had graduated from one idyllic life to another. “I look back at that time, and I go, ‘Man, you were 19 years old, you were living on the northern beaches of Sydney.’ I was getting paid 3,000 bucks a week, which was a lot of money where I’d come from. I was surfing in the middle of the day on set if I had a break, I was experiencing fame, I was a young single guy.” He wonders now why he spent that time panicking about his career. “Why didn’t you enjoy that? We can waste years by saying, ‘Ah, when I get here it’ll be okay. When I get here it’ll be okay.’ We just keep moving that bar until we get to that place.”

Hemsworth saw life as a series of ladder rungs leading to stardom, and he couldn’t stop climbing. Even if the climb felt stressful. Hemsworth still remembers an early television appearance on an episode of The Saddle Club, a Canadian-Australian co-production, in 2003. “I came in as the young vet, and I remember I was so nervous. And you can see, if you look it up on the Internet, my voice is so high, so tight. I’m, like, having a proper panic attack on-screen.” Hemsworth was certain that the flop had doomed his career, what with the huge reach of the show and all. “I remember being close to tears, talking to my mum about it and being like, ‘The show gets shown in Canada, so they’re gonna see it, and Canada is close to America, so Hollywood is gonna see it, and I’m never gonna work again.’ That was my second job—no one gives a sh*.”

That newfound recognition—that mistakes aren’t always fatal and first impressions aren’t always final—was useful as Hemsworth helped push the Thor trilogy forward in Thor: Ragnarok. “The first one is good, the second one is meh. What masculinity was, the classic archetype—it just all starts to feel very familiar. I was so aware that we were right on the edge.”

Confident though he may have become on set, Hemsworth is, right now, very apprehensive in the hotel gym. See, he needs a mat. The women have a mat, but he really doesn’t want to go over and ask them where they found it. So he stalks the gym, looking for a secret mat stash. He tugs on a mirror that looks like it might be a cabinet. Nothing. He resigns himself and approaches the women, now splayed out on the floor.

As Hemsworth appears above them, they freeze. She stares up as he asks about the mat situation, and she does not move until her friend reports that there are no more mats. Hemsworth mutters a defeated “ah” and quickly marches away to discourage further discussion.

The women linger for a few minutes more and then abandon their mat and quit the room—but not before one last long look at Hemsworth.

For a man of Thor-like proportions—he’s six feet four—Hemsworth can contort himself into some pretty childlike positions. Even in a fancy restaurant. Slumped across the table from me, he’s got his right leg folded up almost to his chest, knee level with his chin, his giant desert boot planted firmly on the leather seat.

In 2014, burned out from the increasing hassle of paparazzi in Los Angeles, Hemsworth and his wife went in search of quiet. They visited Australia, and Pataky, who is from Spain, wasn’t initially impressed. “Both trips we did, it was like pouring rain. And she was like, ‘I don’t know what the big fuss is.’ Then I said, ‘Let’s do a trip up to Byron Bay,’ and we get off the plane and it’s raining. I’m like, ‘I’m not selling it.’ And she instantly went, ‘No, there’s something different about this place. It is a very special place.’ She went, ‘This could be it. It could be the best decision we’ve made.’” They moved near the easternmost edge of Australia—to Byron Bay, a gorgeous beach town perched on steep cliffs that plunge straight into the ocean.

The charm of Hemsworth’s life by the sea can be glimpsed on Instagram. “The social-media side of it is just trying to work out: How do you keep up with the times? You see that Sylvester Stallone has an Instagram account, and you kind of go, ‘This is the world we’re in.’”

When Hemsworth shares shots of his kids, his 20 million followers go especially crazy. “In the few and rare times that he does, it’s genuine,” Waititi observes. He’s not curating anything; he’s just proud. “It’s ‘Here’s this amazing moment when my daughter was surfing!’” Waititi says with a laugh.

Still, Hemsworth and Pataky are both careful not to show their children’s faces in photos. “The exploitation is something I’m very wary of. We’ve been offered things, like ‘Advertise such-and-such and have dinner with your family.’ There’s no way.”

Even on a relatively remote bay in Australia, the threats of fame can crop up. Recently, Hemsworth was out with his son when he spotted some paparazzi. He tried to ignore them, but then one of his sons took off his bathing suit. “He’s naked, and I look over, and they’re still shooting. I ran over, and they knew. I just very pointedly and definitely said, ‘Don’t you dare.’ I was close to destroying the camera.”

Gone are those old uncertainties—the occasional feeling that he was a passive player in his own career. Gone, too, are the old assumptions about what it might take for him to thrive. “I came into Hollywood thinking I had to be Russell Crowe. I loved his performances, and because of my physicality and my size, that was the obvious choice. I think I was aware that it could kind of get me in the door. But it wasn’t me.”

“I really do feel a sense of ease for the first time in years. I don’t mean that as an assessment of my achievements. I just mean I’m content with what’s going on and relaxed and open about it.”