Things could have been very different.

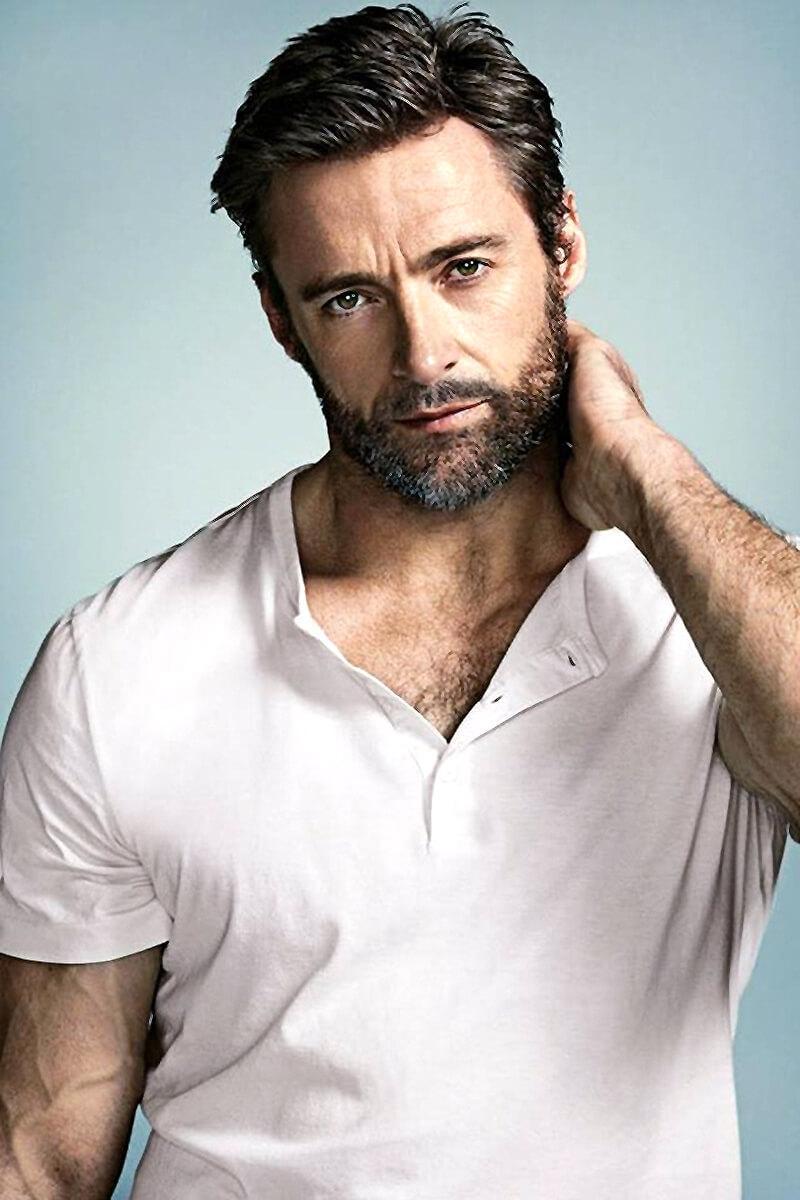

It’s October 2007 and Hugh Jackman’s hair rides high above amber aviators and a grey, mercerised suit.

There’s a helicopter, sequined showgirls and an unnecessary number of high fives. The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” is slowly being strangled.

The eventual credits to Viva Laughlin – an American reworking of acclaimed British series Blackpool – present Jackman as both protagonist and producer. CBS backed the song-and-dance drama, opting to introduce it with CSI (read: millions of viewers) as a lead-in. It premiered on October 18 and was buried – presumably deep in a desert pit – four days later.

Jackman – Teflon Jack – walked away unscathed. A-list all the way.

Today on the touristy fringes of Sydney Harbour, a ceremonial funeral is playing out in the Chinese Gardens, cloaked in mourning. The scenario descends into chaos as those gathered clash violently – a sea of swirling samurais and swords. And there’s Wolverine!

Chatting to GQ between takes, Jackman is quick to warn of Wolverine’s weaponry.

“They’ve cut deep more than once,” he says. “And not just me.”

He presents the claws – a series of sharp steel lengths moulded to a central piece of rubber that sits neatly in Jackman’s palm. They’re heavier than expected.

His smile comes easily – something he’s well known for – but in this case, there’s extra reason: the fact he’s back home and out front as X-Men’s favourite mutant.

“I’m as happy as a clam,” he says. “And I’m really thrilled that the studio called it The Wolverine instead of Wolverine II. Because what we’re trying to set up is a standalone picture that’s going to feel very different, tonally, to any of the other X-Men movies. It’s got massive action sequences, which is what people expect and which are fun. But it’s a character-driven sort of movie. This is what I would like to call the ultimate Wolverine. You get to see more of him than the original story, you see who he is – vulnerable, and faced with not only his lowest point but the choice of embracing who he is or not. It’s all about him.”

Similarly, Wolverine is all about Jackman. He’s previously joked that his role in the series, which he’s now handled six times in varying capacities, is “the kids’ college fund”. And to think the role was first offered to Dougray Scott, who was forced to turn it down due to a scheduling conflict with Mission: Impossible II.

“This has pretty much been the backbone of my career. It was the first [Hollywood] job I got and there have been a hell of a lot of jobs and opportunities I’ve had off of it. When we started with this, comic-book movies were pretty much cold, it wasn’t really a genre. “Since then I look at a lot of comic-book characters and Wolverine is certainly one of the more interesting, layered, fun and bad-ass. And I really enjoy playing him.”

You can tell he means it. His affinity with the brute is honest – this is certainly no sell-out.

“Hugh is a unique character with his affability and his generosity,” offers director James Mangold (they also worked together on 2001’s Kate & Leopold). “I’ve always found a great kinship with Hugh – we have similar personalities and we trust each other, and that is everything. It’s important to make a film with love and Hugh is very much a part of that plan for me.”

Jackman is also producer on this project – which gave him plenty of sway when it came to campaigning to shoot almost the entire film here in Australia. “I was excited to be able to ring the prime minister and tell her that this was a win–win,” he says, proudly.

The resulting shoot is a multimillion-dollar windfall – not counting what the imported stars spent during their Sydney sojourn. What Jackman likes even more is the opportunity such a large production provides to the local industry.

“Jim [Mangold] said to me the other day, ‘Man to man, this is the best crew I’ve ever worked with.’ He is blown away. And without movies like this it’s very hard to keep training and keep that machine going. You forget that in Australia we’ve won several Oscars in recent years for cinematography. There’s a lot of attention on actors, but cinematography is about a crew, and that takes time.”