We find ourselves ensconced in a 14th-floor suite at Hollywood’s W Hotel — chosen because Pitt’s Cadillac Escalade can make a quick in-and-out to avoid the paparazzi thirsting to behold him.

Pitt doesn’t blame them. Media reports surfaced hours earlier that police had interviewed his bodyguard about remains near the Hollywood sign. Still, he can’t help being bemused. “I was watching CNN, and they said, ‘Brad Pitt’s home!’ and, ‘Brad Pitt’s bodyguard!’ ” he laughs in disbelief. “I’m like: ‘Why? Why?’ “

The report is nonsense, of course. His security chief happened to pass a policeman who asked if Pitt’s surveillance cameras had recorded anything strange, which led to CNN’s proclamation: “Police interview Brad Pitt’s bodyguard, search Hollywood Hills for more body parts.”

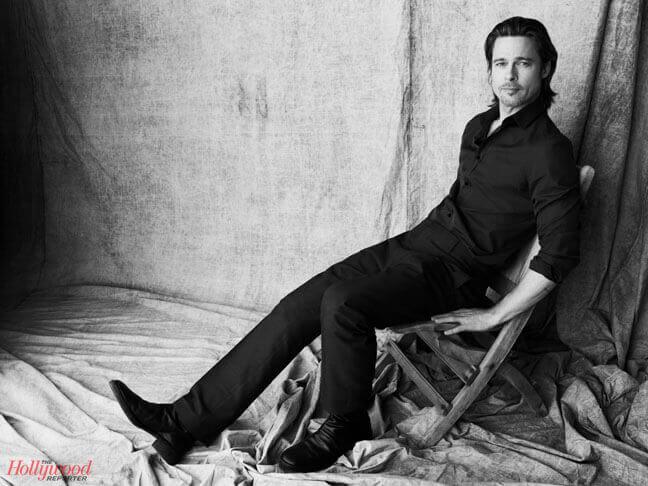

Rarely ruffled and polite to a fault, he leans casually against a window revealing a previously unnoticed tattoo on the inside of his forearm. It’s an outline of Otzi the Iceman, found frozen in the Alps in 1991, some 5,300 years after his death. Next to him, a series of numerals specify the height of the General Sherman Tree, a giant sequoia in Central California. Beside that, there’s an inscription in French: absurdité de l’existence — the absurdity of life.

Pitt knows something about this. He’s a man who can make $10 million to $15 million a film — work vastly enhanced by his growing stature as a producer, including Moneyball, a movie he saved from the clutches of death.

But he’s also Pitt the Celebrity, not once but twice half of the most famous couple alive — first through his marriage to Jennifer Aniston, then through his relationship with Jolie.

Despite a quarter-century as an actor, Pitt [the celebrity] has overshadowed the actor-producer. He has multiple Oscar nominations — two for acting in and producing Moneyball and probably a third as a producer of Tree of Life (the Academy has yet to determine which producers qualify). “It’s a great honor. “And Tree of Life! I’m doubly excited because we felt we were all but forgotten.”

“I’ve always been at war with myself, for right or wrong,” he admits. “I don’t know how to explain it more. There’s that constant argument going on in your head about this or that. It’s universal. Some people are better at dealing with it, and they sleep with no pain — not pain, arguments. I’ve grown quite comfortable with being at war.”

He discusses the architects he has worked with to develop low-income housing in New Orleans; the marvel of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove; his struggle to learn French (which he speaks “comme ci, comme ça“); and his love for Egon Schiele, an Austrian artist deemed “decadent” by the Nazis, whose style came to mind when he first saw that image of Otzi.

Even when we broach the subject of Jodi Kantor’s new book “The Obamas”, which describes Pitt as “awkward” in a meeting with the president (“I probably was — you don’t want to impose on a busy man,” he says), he’s more interested in Obama than himself, particularly whether the commander in chief has stopped smoking, as Pitt would dearly like to do. While backing Obama, he nonetheless was glued to the Republican debate Jan. 19. “I’m an Obama supporter, no question. But it doesn’t mean there’s nothing to learn from the other side.”

All his life, Pitt has learned from the other side. “I grew up very religious, and I don’t have a great relationship with religion. I oscillate between agnosticism and atheism.”

He oscillates, too, on the subject of whether he’ll get married, and it’s clear Pitt has shifted from his promise that this won’t happen until gay marriage is legalized. “We’d actually like to,” he says of his seven-year partner, Jolie, “and it seems to mean more and more to our kids. We made this declaration some time ago that we weren’t going to do it till everyone can. But I don’t think we’ll be able to hold out. It means so much to my kids, and they ask a lot. And it means something to me, too, to make that kind of commitment.”

“I’m not going to go any further. But to be in love with someone and be raising a family with someone and want to make that commitment and not be able to is ludicrous, just ludicrous.”

Indeed, throughout our conversation he’s willing to discuss almost anything always in a manner that seems temperate and respectful.

“If you look at where Brad came from and charted the transformations he has realized, you’d recognize this is a person who’s staged multiple revolutions in his life and career,” says Moneyball director Bennett Miller. “There’s a revolutionary spirit there.”

“There were many revolutions,” he agrees.

The idea of making a movie about math, as Pitt jokingly describes Moneyball, is one of them.

The project began its long journey five years ago, when Sony Pictures co-chairman Amy Pascal showed Pitt Michael Lewis’ 2003 nonfiction book about baseball team GM Billy Beane and the statistics wunderkind who helped him transform the Oakland Athletics. At the time, writer Stan Chervin and director David Frankel (The Devil Wears Prada) were developing it with a decidedly comedic touch. Pitt looked at the screenplay, and at Beane himself, and wanted to go in a different direction. “I read the book, and this idea of second chances and how we sometimes let ourselves be rated too much by others — we put so much emphasis on a paycheck or what a magazine says — made me think, ‘Oh my… there’s something much bigger here.’ “

He offered to leave the film with Frankel, but the director graciously departed, allowing Pitt to develop the story as he saw fit. Not a baseball fan, it was the nuances of Beane’s character that intrigued him. And so… he brought on Steven Zaillian (Schindler’s List) to script and asked his friend Steven Soderbergh (Ocean’s Eleven) to direct.

Pitt comes alive recollecting the enthusiasm he felt at getting them all on board, but after Soderbergh reworked Zaillian’s screenplay, Sony had second thoughts. “We were supposed to leave on a Sunday to start shooting, and Steven handed it in on a Wednesday or Thursday, and the studio was not feeling good. It’s not that they didn’t like the idea; they did not like the price” — about $60 million.

Pascal pulled the plug. She gave Soderbergh and Pitt several days to shop the project but everybody passed. “Nobody wanted to buy disgraced goods. It was dead.”

But Pitt refused to let it die, calling Pascal and urging her to stick with the movie. “There would be no Moneyball without him,” says producer Scott Rudin. “He saved it single-handedly, and he deserves the credit for its existing at all.”

Pitt approached Miller who flew from New York to meet him.

Pitt was cautious, given that Miller had made nothing since Capote (2005). “It’s usually a warning sign when a director doesn’t work for many years, but it’s because he’s so choosy. The fact he had such an investment in the material — which was apparent in our first meeting — was a big green light for me.”

Now he had to persuade the studio. “There was a lot of disagreement about where this should go.”

With Aaron Sorkin brought in to rewrite, and with Rudin added as overseer, Pitt and Miller reworked every element during the following nine months.

“We talked a lot about documentarians and 1970s films and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest — and how the character in that movie is the same beast at the end. That was relevant, because some people involved wanted to have a big epiphany and change, which wasn’t true to life.”

The filmmakers resisted attempts to reduce Beane’s journey to the “arc” of a conventional Hollywood script. “I had some sleepless nights. It was not without its pressure.”

His determination to buck tradition continued when he began preparing to shoot the film, having long conversations with Beane and hanging out to talk ball with the players. It carried into the shoot, when Pitt backed Miller’s decision to use long shots rather than close-ups, letting them play without quick-cutting, an “elegance” Pitt admires.

None of this was accidental; none of it would have been possible without Pitt’s willingness to challenge authority. “I do have a kind of knee-jerk reaction to go the other way than I’m supposed to,” he notes slyly.

The result is a best picture nomination, along with the one for Tree of Life, which Pitt also made through Plan B Entertainment. Together, they show Pitt the producer and Pitt the star working spectacularly in tandem, with a boldness and depth nobody could have imagined when he started acting some 25 years ago.

Born in Oklahoma, Pitt grew up in Springfield, Mo., with two younger siblings. “This was Huckleberry Finn country, Mason-Dixon Line, where televangelism was born.” It gave him a certain mistrust of “government and any power that may be above us and could oppress us; but that mistrust transcends into anything not like us — that’s the flip side, the not so nice side” he’s proud to have overcome.

“My dad came from nothing, an outhouse in the middle of winter, walking to school, and was really determined to give us what he didn’t have.”

“[His mother, Jane] is very, very loving — very open, genuine, and it’s hilarious because she always gets painted in the tabloids as a she-devil. There’s not an ounce of malice in her. She wants everyone to be happy.”

Pitt says he has aspects of both. “I can be naïve like my mom sometimes, but I’m like my father. Every film I do, there’s some connection to my dad, though my father’s got a toughness. He’s probably tougher than I am.”

“I always knew I was leaving. I didn’t know where I was going, but I knew there was so much more to see and learn. I was always looking out and beyond — and movies were a big part of that for me. Film shows you other [paths].”

He remembers going to the local drive-in with his family, sitting on the hood of the car on “really humid, hot summer nights,” eating homemade popcorn because they couldn’t afford the concessions and being overwhelmed by 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. “This idea of loss, when they get killed at the end and they’re gone, just shattered me” — an awareness of death that lingers and influenced his choice of tattoo.

But film was not a career option, so he majored in journalism at the University of Missouri. Then, right before graduation, “it just struck me: I was done.”

Two weeks before earning his degree, with $325 he’d made from working on his father’s loading dock, he drove to California in a beat-up car and stayed in the Burbank home of a family friend. He didn’t even tell his parents he was planning to act; he said he was going to investigate Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design.

He remained in the Burbank apartment for a month. “It was me and a Thai maid who couldn’t speak English. I stopped immediately and went to McDonald’s, had a meal, got the trades, and by the end of the week I was doing extra work and pretty excited about it.”

Soon, he was acting, with a four-episode stint on Dallas. But Pitt truly galvanized the public in his role as the abs-gifted grifter who seduces Geena Davis in 1991’s Thelma & Louise. With that simple sequence, every agent and executive knew a major star was born.

“Look at those directors he’s worked with — Terrence Malick, Soderbergh, Robert Redford, David Fincher, Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers. They all know just how good he really is,” says Pascal. “People think of him as an actor, and he’s so much more.”

While Pitt’s star ascended with 1992’s A River Runs Through It, 1994’s Legends of the Fall and 1995’s Seven, his personal life declined, even following his 2000 marriage to Aniston.

“I got really sick of myself at the end of the 1990s: I was hiding out from the celebrity thing; I was smoking way too much dope; I was sitting on the couch and just turning into a doughnut; and I really got irritated with myself. I got to: ‘What’s the point? I know better than this.’ “

“I used to deal with depression, but I don’t now, not this decade — maybe last decade. But that’s also figuring out who you are. I see it as a great education, as one of the seasons or a semester: ‘This semester I was majoring in depression.’ I was doing the same thing every night and numbing myself to sleep — the same routine: Couldn’t wait to get home and hide out. But that feeling of unease was growing and one night I just said, ‘This is a waste.’ “

His comfort level already had been shaken during a prolonged trip to Yugoslavia for the filming of 1988’s The Dark Side of the Sun, before “ethnic cleansing” (the subject of Jolie’s In the Land of Blood and Honey). Even then, “They were talking about it and you could see the hatred. It was like the Hatfields and McCoys — as soon as they heard a name, it put them on the other side of the fence, and that left an indelible mark on me.”

So did a trip to Casablanca, Morocco, in the mid-to-late 1990s, “where I saw poverty to an extreme I had never witnessed before, and we talked about inequality and health care, and I saw just what I felt was so unnecessary, that people should have to survive in these circumstances — and the children were inflicted with a lot of deformities, and things that could have been avoided had become their sentence. It stuck with me.”

Almost overnight, he decided something had to give. “I just quit. I stopped grass then — I mean, pretty much — and decided to get off the couch.”

Not one readily to discuss such intimate things — “probably one of my faults is that I don’t go to this wealth of knowledgeable people I have around me; I don’t do that enough, and it’s part of the Southern thing of not wanting to show weakness” — he nonetheless reached beyond his inner circle.

“I sought out Bono and sat down with him a few times and got involved in some of the stuff he was doing. But it all started before that. It started with private acts,” which he doesn’t define.

Inevitably this led him to Jolie. While the tabloids gloat about her effect on Pitt, the two were drawn to each other by corresponding concerns.

“That may have been one of the things that brought us together. Certainly, I’ve met very few people more dedicated than she is. She is always studying issues, daily. She has such compassion for the people she works with.”

He found the same compassion growing in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which hit him hard as he’d grown to love New Orleans, where he’d spent three months filming 1994’s Interview with the Vampire. “The first thing that rang wrong to me was when it was being called an act of God,” he says with an unusual flare of rage. “And it wasn’t an act of God. It was an act of human failure and marginalizing people and the areas that contain these people.”

Despite being told, “Don’t go near it” Pitt felt “there was a responsibility to make it right, which was not being answered wholly, so I decided to make that a focal point and help families return home — and in the process we started discovering the inadequacies in low-income housing, that it actually keeps a family trapped at a low-income level. There are a lot of shoddy appliances that drive up utility bills to hundreds and hundreds of dollars, and that can make or break a family.”

Through his Make It Right Foundation, created in 2007, Pitt began building environmentally friendly homes at a competitive price. He organized 21 architectural firms to construct 150 single-family houses and duplexes in New Orleans and gave millions in donations.

He marvels at the result, having seen poor families living healthy lives with manageable bills. “It’s remarkable and now we want to take what we’ve learned and expand to other parts of the U.S. and abroad.”

Pitt is currently developing projects in Newark, N.J., and a tuberculosis clinic in Ethiopia. The Jolie-Pitt Foundation has given millions to charities including SOS Children’s Villages, Community Foundation of the Ozarks and Naankuse Wildlife Sanctuary in Namibia, among others. The Chronicle of Philanthropy estimates Jolie and Pitt donated more than$8.5 million in 2006 alone.

As one executive familiar with their nonprofit work notes, “You have no idea how much money they give away. It’s millions and millions and most people never even hear about it.”

What they hear about instead is the Jolie-Pitt brood, and Pitt is at his most passionate when speaking of his kids.

Having children, he says, has been “the most grounding thing.” Would he have more? “We haven’t closed the book on it. There’s a really nice balance in the house right now, but if we see the need and get that lightning bolt that says, ‘We can help this person; we could do something here,’ then absolutely.”

It was while carrying Vivienne that Pitt fell and hurt his knee, causing him to walk with the cane his friend George Clooney spoofed during the Golden Globes.

It wasn’t a skiing accident, contrary to reports. “I think George went down the line, making things up,” Pitt laughs. “I was just walking in our backyard, on a hill, carrying my daughter, and I slipped — and it was those parental instincts: me or her. And she’s fine.”

He jokes about how his children kept stealing the cane until he gave them canes of their own. He still wears a leg brace and can talk in great detail about how “I just tweaked this MCL [medial collateral ligament] — I got a whole tutorial. I know all about the knee.” He’ll wear the brace another month before commencing physical therapy.

As for the children, they’re home-schooled because “we travel a lot. We were with a program that we could plug in internationally. But it wasn’t the same standard everywhere, and we wanted to be able to tailor something to our kids; they’re such individuals.”

It’s partly because of them that he’s learning French, and also because of that need he has to keep reaching for more.

“I’m frustrated going to other countries and not being able to converse with everyone, and we’re trying to spend some time in Europe and use that as a hub. I want my kids to have the gift of other languages; it wasn’t an emphasis where I grew up. But those synapses close down — they’re fused shut and I’m trying like mad to open them again.”

These interests and passions can pull him in a million directions, and he admits to occasional indecisiveness, an area where he points out Jolie’s influence. “She’s very quick, she’s very decisive — and that’s had a great effect on me. It’s her decisiveness that I have so much respect for.”

Jolie’s unseen presence makes itself felt throughout our conversation, and his love for her is unmistakable. But the notion that she’s somehow reshaped this highly thoughtful man is a myth — at least, any more than he’s reshaped her. Like her, he wants to do work that survives; like her, he is committed to the world at large. Unlike her, he claims to have no gift for the gab.

“My great frustration is, I can’t explain what I’m trying to explain!” he sighs, throwing up his hands. “I’ve got the vocabulary of a public school education and the grammar of an eighth-grader.”

It’s not true, not the tiniest bit, but just one aspect of a man constantly questioning himself, only “satisfied in not being satisfied.”

In his life and in his work, he is forever stretching boundaries — as he will in his upcoming films World War Z and Twelve Years a Slave.

The former, based on the Max Brooks book about a global zombie war — and the first of a planned franchise — drew him because “I thought it was an interesting experiment. I thought, ‘Can we take this genre movie and use it as a Trojan horse for social-political problems?’ “

The latter tells the story of “a free black man in the north who is kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South. I’m only doing a small cameo, but it stars Michael Fassbender and Chiwetel Ejiofor and there’ve been very few movies about slavery, certainly that had the impact of Roots.”

Having such an impact is at the heart of everything he does, and it’s much more important to him than conventional happiness.

“This idea of perpetual happiness is crazy and overrated, because those dark moments fuel you for the next bright moments; each one helps you appreciate the other. We are all searching for meaning in our lives, love and betterment for ourselves and those around us.”