Two years after River Phoenix’s death, a new view of his troubled life emerges

He seemed to stand in the shadow of pain, and sensing this from the very start of his career, directors threw him the heavy stuff. In a 1984 after-school TV special called Backwards: The Riddle of Dyslexia, 13-year-old River Phoenix played a child crushed by his secret reading impairment. The drama is slight, but River¹s portrayal is subtle, uncompromisingly real. In the following year, he made Surviving, a compelling movie-of-the-week about teenage suicide. River’s character reacts to his older brother’s death by trying to take his own life. “Seeing someone that young express such despair,” recalls his co-star Zach Galligan, “was astonishing.”

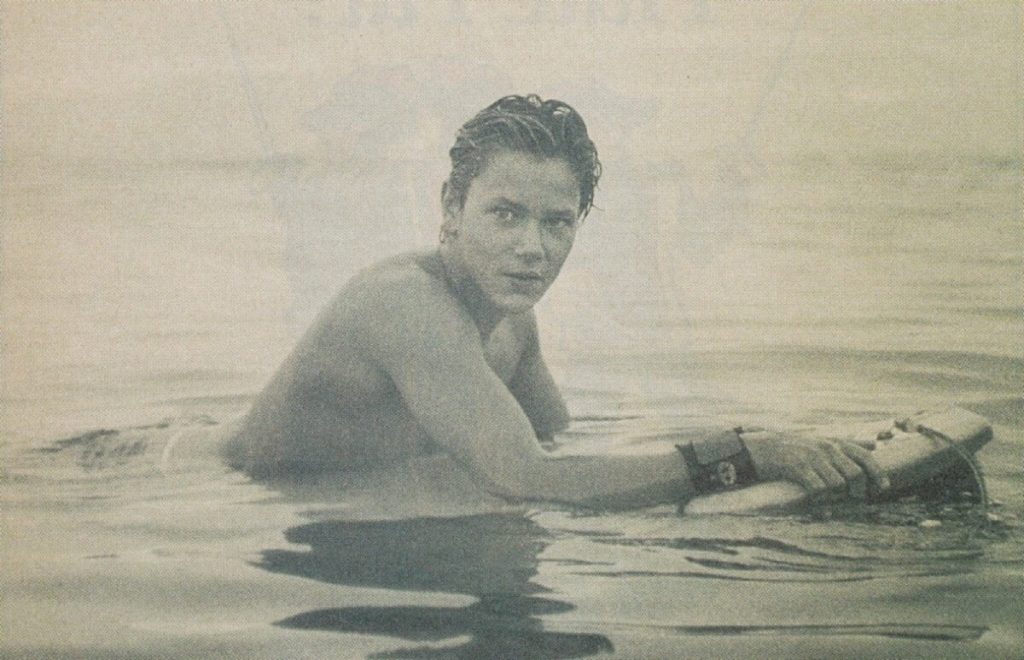

River Phoenix is mostly remembered, though, for his riveting performances in such films as Stand by Me and My Own Private Idaho. These roles brought him fame and established him as a kind of icon of the vulnerability of youth. His headline-making death nearly two years ago at the age of 23 perpetuated the mystique.

It’s tragic with a new twist. As an adolescent, he would become the family breadwinner, playing out his scrambled childhood in make-believe, big screen adventures. But as a young man, overwhelmed by the same inner conflicts that gave his acting such resonance, cut down by the excesses of a Hollywood lifestyle he both denounced and pursued, he became like many of his characters – lost.

“There was so much to River’s personality,” says a colleague, “so much sweetness and eagerness and talent that you couldn’t help but love him. He could be so funny, but there was also an unsettling strangeness underneath it that made you wonder about the rumors of his past. I kept asking myself: ‘What kind of crazy, confused childhood did this kid go through? What’s his story?'”

Phoenix was raised at the crossroads of 60s idealism and cultism. His mother, Arlyn Dunetz, was born in 1944 and raised in a middle-class section of the Bronx. In her early 20s, bored with the constraints of a dead-end secretarial job and with her conventional husband, she headed for California. Hitching west in 1968, she was picked up by a man who would become River’s father, John Bottom, a high school dropout and an absentee father of a baby girl, from Fontana, Calif. Bottom, who was several years younger than Arlyn, was a sometime carpenter and had been on the road since his teens.

The couple clicked, smoking grass, dropping acid and, in short, living the peace-and-love lifestyle. They drifted up the Pacific coast, doing odd jobs like farming or picking fruit. In the spring of 1969, they found a hippie commune on a mint farm near Madras, Ore.

It was there, on Aug. 23, 1970, that they had their firstborn, River Jude, named for the River of Life in the novel Siddhartha and for the Beatles’ ballad “Hey Jude.”

Before long, the new family became members of an evangelical cult, the Children of God. With its anti-establishment spirit, the group appealed to the Bottoms’ sense of idealism, while bringing structure to their lives. Its leader was a self-styled prophet named David Berg who had started attracting followers a few years earlier in Huntington Beach, Calif., where he had served up peanut-butter sandwiches and folk music by the pier. Followers were taught that Berg’s writings were the only true word of God and superseded the Bible. One of his daughters, Deborah Davis, who wrote an expose in 1984 called Children of God: The Inside Story, described the cult as “the gospel of rebellion,” appealing mostly to burnt-out hippies alienated from conventional society. By the time the Bottoms joined, Berg had become strange and secretive. His movement, though, had thousands of followers with colonies stretching from South America to Asia.

In 1973, Arlyn gave birth to a daughter, Rain Joan of Arc, at an abandoned school the cult had taken over near Crockett, Texas. From there, the group sent them first to Mexico, then to Puerto Rico, where Joaquin Rafael – who would later rename himself Leaf only to change it back again more recently – was born in 1974.

“I remember when we arrived in Caracas in the beginning of 1976. The Phoenixes, including their three children, had been there about six months,” says Ado, a member of the Family (the new moniker of the Children of God), whose followers often eschew last names. “We lived together under the same roof and became best friends. They hadn’t started to use the name Phoenix. Arlyn and John were the shepherds, or supervisors, for the whole country. That meant overseeing nine or ten homes.

“It was in Venezuela on Liberty Day in 1976 when they had their second daughter, Liberty Butterfly,” Ado continues. “They were devoted parents, and we took many camping trips together with our kids. I do remember them telling us that one reason they joined [the cult] was to stay off drugs.

“Only later did Arlyn and John say that they worried about leading their kids on such a vagabond journey. I reassured them it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see the world while doing good work. And when the kids began performing, well, that was something that would always stick with them.”

At that time, according to Ado, group members supported themselves through “provisioning,” which he describes as “asking local businesses for supplies and donations,” as well as “witnessing,” or the selling of propaganda. But Deborah Davis and others note that the group depended on children to attract money and converts: smiling children singing in parks, handing out brochures, begging for donations in the name of God’s love.

Ado says, “Every Friday night, the kids sang in the plaza Candelaria. River and Rain were the stars. River would sing in perfect Spanish. He had great facility on the guitar, which was as big as he was. The boy could attract a crowd.”

In 1977, with no advance word to their best friends in Venezuela, the Bottoms left the Children of God. Arlyn would later tell a journalist that she and her husband were opposed to the cult’s use of sex to win new converts.

“The guy [Berg] running it got crazy,” she explained.

Around River’s seventh birthday, the family was destitute, living in a squalid beach hut in Caracas. With no resources, the Bottoms turned to a missionary in Caracas, a liberal minded Catholic priest from the states named Father Stephen Wood.

“I first befriended members of the Children of God in Venezuela in the early 70s,” Father Wood recalls. “I was bothered by their begging. When Arlyn and John showed up one day at my parish door, they told me they decided to leave to follow the Bible. They had no food, no money, no place to stay, no way to get back to America.”

Father Wood, who housed a dozen newcomers under his roof at any given time, invited them to stay with him. Once he saw how talented River and Rain were, he let them perform at Sunday Mass.

“I got the feeling that parents in the Children of God were exploiting their kids’ talents, aware that the kids were more effective beggars than them,” he says. “Over the years, as we stayed in touch, Arlyn and John would explain, ‘We manage our kids’ careers,’ but I always felt ambivalent with that dynamic. Once they left the cult, they never had any profession except for being the parents of these talented progeny.”

After several months, the priest got the Bottoms to take jobs as caretakers of a beach house; and later, when they decided they wanted to return to America but couldn’t afford to, he helped arrange free passage for them on a cargo ship bound for Miami.

It was back home in America that the couple rechristened themselves Phoenix.

Living with Arlyn’s parents in Winter Park, Fla., Arlyn, who would later rename herself Heart, gave birth to her fifth child, Summer Joy, in 1978.

Money was still in short supply, and in desperation the former evangelists followed a basic lesson learned in the cult: They turned to their two oldest children. Aged 9 and 7 respectively, River and Rain smiled and sang and began winning amateur talent contests. A profile of them in the St. Petersburg Times found its way to a staffer in the casting department at Paramount Pictures. When a form letter was sent back inviting the family to drop by should they ever be in Los Angeles, Arlyn interpreted it as a sign, pulled up stakes and pointed the tribe toward California.

Later, she would explain, “We had the vision that our kids could captivate the world.”

Once in California, Arlyn found work as a secretary for Joel Thurm, then head of casting at NBC, and on his advice, she went to see a children’s agent, Iris Burton, who signed up the whole brood. Almost immediately, River seemed salable, pitching Ocean Spray juice and Mitsubishi cars. Then, at 10, he found his conscience and told Arlyn he wanted out. “Commercials were too phony for me,” he’d later remark. “It was selling a product, and who owns the product? I mean, are they supporting apartheid?”

For a year, River failed to land an acting role. He and Rain spent their free time singing and song writing. Eventually, he nabbed the role as the youngest son in a family-oriented series for CBS’ 1982-83 season, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. The show was canceled after 22 episodes, and River, now the family breadwinner, had to look for work. Before long, he landed parts in two TV miniseries and guest cameos on Family Ties. With the 1985 release of Explorers, River made it to the big screen.

Many of the conflicts Phoenix faced during adolescence – finding a place in a society he was originally taught to shun, being prematurely forced into a position of familial responsibility – were mirrored in the characters he portrayed.

In Rob Reiner’s 1986 hit Stand by Me, Phoenix’s character is tough beyond his years, a child of outcasts. Displaying unusual wisdom and maturity, he reverses roles, becoming the emotional father to his three 12-year-old buddies.

Australian director Peter Weir pushed Phoenix even further in The Mosquito Coast, casting him as Harrison Ford’s oldest child. The autobiographical echo is clear: A rebel father – eccentric, single-minded, scornful of American society – uproots his family, robbing his children of a normal upbringing.

With Sidney Lumet’s Running on Empty, the theme reappears, only now the parents are 60s radicals on the lam from the FBI. In this film, the emotional pressure on the son to save his outlaw father nearly destroys him. Phoenix’s memorable performance, at age 17, won him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor.

The nomination confirmed the widespread recognition he was gaining. Like his fans, many of his colleagues were awed by Phoenix’s talent and intrigued by the mystique of his off screen life. For some cohorts – including one who also has had to deal with the pressures of being a young star who actually worked with him early in their careers – the intrigue lasts.

Ethan Hawke is slumped at a back table at Man Ray, a sleek art deco restaurant in Manhattan’s Chelsea district. Hawke is somewhat rumpled and distracted; tomorrow he’s going abroad to work on the movie Before Sunrise. He speaks in spurts, a fast talker with a quick mind. His boyish charm is tinged with the knowing edge of a pro.

“River and I were barely 14,” he begins.” “We were cast in Explorers. That was the first film for both of us – I’d never acted before, and River had done some TV. It was the longest shoot I’ve ever had. Six months with River Phoenix. Man, was it intense.”

The film focuses on three teen-agers who build a makeshift space capsule that flies to another galaxy. The boys represent three different types: Beauty (Ethan), Brawn (Jason Presson), and Brains (River).

“We tested River first for the brawny, then the brainy, part,” says Joe Dante, the film director, “knowing he could do either. He had a remarkably fresh, nonactorish quality. He agreed to play the scientific-minded Wolfgang. River had to do the most acting of all the kids since he was playing against type. He had to cut his hair and wear dorky clothes and glasses, which he’d take off the moment a girl came around.”

Hawke recalls: “We competed for the attention of girls like crazy. In fact, we competed over everything. We bragged and boasted continually about sex. The truth is we were both virgins. I guess it’s touching to look back on two teenage boys struggling with hormones.”

“What’s not touching,” he adds, “Is the phenomenon of child acting. I believe it is profoundly negative and hurtful. Sure, it’s natural for kids to act in school plays, but to be adulated by fans is not natural. It’s not natural for a 14-year-old to have adults fetch him coffee.”

Hawke remembers Phoenix as charming but filled with “naïve pretentiousness.” “To me,” he says, “education helps you see that your weirdness is not unique. I doubt, though, that River, at age 14, had read a book. He thought his ideas on life and the environment were original. Because he’d never been to school, he had no social skills, and lacked a sense of what was appropriate conversation.”

Phoenix’s father, others have observed, had a drinking problem. “One day John showed up at a looping session obviously drunk,” recalls an eyewitness on the Explorer set. “River tried to laugh it off, saying, ‘My dad, well, he gets funny sometimes.’ But you could see the kid was hurt and embarrassed.”

Hawke evokes another memory: “One night River asked me, ‘Are you going to be famous?’ At the time I played up a certain false humility. ‘I don’t know, I don’t care much,’ I said. ‘I’m going to be famous. Definitely. Rich and famous.’ I was impressed by his directness. ‘Why? What’s so cool about fame?’ I asked. ‘I’m doing it for my family,’ he answered. After that night, I really saw the heavy trip his family had laid on him. To them, he was the man of the house at age 14. Maybe that’s why River always took himself so seriously.”

Explorers was neither a critical nor commercial success. But Phoenix’s next outing, Stand by Me, launched his career. Hawke auditioned for the same film but didn’t make it.

“That further complicated our relationship,” says Hawke. “People back home wanted my autograph because I knew River Phoenix. It would send me into fits of envy. After River did The Mosquito Coast with director Peter Weir, he was dying to do Weir’s Dead Poets Society. The irony was that Peter wanted unknown kids. The fact that I was unknown helped me get the part. River even wrote a song about the Dead Poets Society – that’s how much he wanted to play Bobby Leonard’s part, the character who kills himself. We were friendly competitors. He said he admired my work, but I didn’t believe him. He liked to play head games.”

Hawke pauses for a moment, his voice becoming a little sadder. “Martha Plimpton was his first real girlfriend,” he goes on. “Martha’s wonderful and extremely smart, but it wouldn’t be easy to have her as your first girlfriend. She doesn’t buy any bulls*. In a way, that must have been good, because Martha would never tolerate drug abuse. But River and Martha didn’t last.

“For all my mixed feelings about River,” says Hawke, “I realize how much I wanted to work with him again. Even though he was only six months older, I understand now that he was years beyond me in artistic maturity. In some ways, I was always trying to catch up.”

Explorers would be the first of thirteen features Phoenix made in nine years. While steadily acting until he died, he was also a passionate musician. Music, in fact, was his first love. He’d take his guitar on location, practicing and writing songs. Early in 1987, Phoenix’s music skills came to the attention of Chris Blackwell, the head of Island Records, who offered him a development deal.

“When River first played for Chris and me,” says Kim Buie, his artist rep at Island, “I thought he was great. At age 17, he was very sophisticated musically. His lyrics, on paper, read like poetry. He was a far better guitar player than he ever gave himself credit for.”

Taking Phoenix under her wing, Buie helped him form a band, Aleka’s Attic, which included Rain Phoenix on keyboards and vocals. The band was very diligent when Phoenix had time off, but the late 80s and early 90s were a busy acting period for him. The band members tried to accommodate his hectic film schedule, but conflicts arose, resulting in a split in 1991.

“River and I stayed friends,” says Buie, “He was constantly writing songs. At first, he was the pleasant, almost folky, singer-songwriter. Then he was getting into more abstract material, layering, complex chord changes, using two bridges. He was definitely ready to make a record.”

Island Records currently has a stack of demo tapes and songs by Aleka’s Attic sitting in the company’s vaults. The only song released by the group, “Across the Way,” is part of Tame Yourself, a 1991 compilation album to benefit the animal-rights organization PETA.

Phoenix liked to combine his music and his morals, by playing at benefits for PETA and other groups and causes, including Amnesty International. He felt that one of stardom’s redeeming qualities was that it gave him the celebrity -and the money – to support his favorite causes. (For example, he purchased hundreds of acres in Costa Rica to preserve local rain forests.) Eventually, though, the trade-off seemed less and less worth it, and by the early 90s, he was more disdainful of Hollywood than ever.

Yet he always enjoyed the company of musicians. During the filming of My Own Private Idaho in Portland, Ore., in 1990, Phoenix befriended Flea, who had a small part in the film. For nights on end, River, Keanu Reeves (also a bassist) and Flea jammed in the house they were borrowing from director Gus Van Sant.

“River loved nothing better than hanging around the Chili Peppers,” reports a long-standing music-business friend of River’s. “They were his big friends and Flea was his man. I remember how happy River was when he was with the Peppers. His beaming face said to me, ‘This is where I wanna be.’

Phoenix’s drug use began early: There are reports of pot smoking during the time he made Stand by Me in 1985 when he was 15. A young film editor who befriended him on the set of the black comedy I Love You to Death recalls, “When we got back to L.A. from shooting in Tacoma [Wash.] during the summer of ‘89, River and I had a great time together. We got drunk a lot – there were recreational drugs, too, but only occasionally, and it was pretty innocent. Later on, that all changed.”

Though Phoenix tried concealing his increasing involvement with drugs, a number of his colleagues were not fooled. A crew member who worked closely with him in the winter of 1992 on Peter Bogdanoich’s The Thing Called Love remembers how hard it was for him to focus. “His behavior suggested that he was on something, though he claimed to be staying out of trouble. Also, his mom was with him, so I really didn’t know.”

A young actor living in Hollywood, who has since gone through rehab, hung out with Phoenix the spring before his death. “We did a lot of drugs together. River had the best pot, plus a supply of Valiums,” he says, “I began getting suspicious at one point – though I never actually saw him shoot heroin – because he displayed some characteristics that don’t go with doing pot or cocaine.

“There also was the time we free-based together for the first time, and he said, ‘Gee, I’ve never done this before,’ but when he did, he knew exactly how to do it. It was a nightmare, really. When he was very high, he’d play and sing these songs with the most bizarre lyrics. Through it all, though, he was an absolute sweetheart.”

Phoenix’s family probably had knowledge of his drug taking – how much and what they did about it is unclear. His mother, who acted as his manager until he died, had moved the family in 1987 to a ranch near the college town of Gainesville, Fla. When Phoenix wasn’t making a movie, he was usually staying at the Florida home, hanging out with friends in the local music scene. John Phoenix, unhappy with his family’s involvement in the Hollywood mill, had been living for a number of years on land the family owns in Costa Rica, where he still resides. The weekend of his death, his brother Joaquin and his sister Rain had flown out to L.A. to cheer him up during his unhappy experience shooting Dark Blood in the Utah wilderness. The trio, along with Phoenix’s then-girlfriend, actress Samantha Mathis, had gone with him to the Viper Room. At the club, co-owned by Johnny Depp, Phoenix was planning to meet Flea.

It was Joaquin who would place a frantic call to 911 while Phoenix – in the throes of a drug overdose caused by lethal levels of cocaine and heroin – suffered convulsions on the sidewalk of Sunset Boulevard in front of the club. It was Rain who cradled his head in her lap as he took his last breaths. When the paramedics reached Phoenix around 1 a.m., he was in cardiac arrest with no signs of a pulse or blood pressure.

The mix of his odd, itinerant upbringing and the pressures of childhood stardom created a raging inner turmoil that Phoenix could mask in person but set loose on the screen. His life and art were interfused.

[credit date=”Oct.1995″