Plunging deep into his roles—from the self-created to the painstakingly re-created —Johnny Depp can drive himself to the edge of the psyche. His decompression is as extreme: a 45-acre private Bahamian island, where he can snorkel among the barracuda. The author joins the 46-year-old star and friends on Depp’s 156-foot yacht, which flies the Jolly Roger, for a stay in this singular paradise.

The notoriously private actor invited Vanity Fair along on a sailing trip to his Caribbean isle. “You’ve got all-access,” Johnny Depp declared. “Ask me about anything you want.” Photograph by François-Marie Banier.

A few feet away, the Caribbean glistens in the last yawn of twilight.

I’m enjoying an alfresco dinner of oysters and mango shrimp, sitting beachside with my host and three new friends. There is a tangle of tropical jungle behind us. And we’re watching the sun sink over the horizon as prisms dance across the seascape.

I am, as it happens, a guest on the private island of Johnny Depp. For reasons that surely once made sense, this Bahamian dollop appears on maps as Little Hall’s Pond Cay. And this idyllic stretch of sand has been re-christened by the actor as Lily Rose Beach, after his 10-year-old daughter.

In this particularly calibrated paradise, every detail has its subtext—of Depp’s own devising. Even though the song that wafts from the speakers is clearly the 1950s Everly Brothers hit “All I Have to Do Is Dream,” the raspy voice sounds like nothing so much as the howl of a prisoner in a torture chamber.

“That’s Keith [Richards]!,” Depp enthuses. “He recorded some of these after his ’77 heroin bust in Toronto. He thought he was headed to jail for 30 f**ing years for trafficking.”

Depp, as if recounting a favorite outlaw fable, then goes on to tell how the Ontario Provincial Police and a team of Royal Canadian Mounties stormed into Keith Richards’s room while he was sleeping and confiscated 22 grams of heroin. (Richards eventually had his sentence reduced from trafficking to possession and was put on probation for a year.)

Depp tilts his head toward the hut. “Listen to this,” he urges, nodding in adoration. Richards, alone on piano, is now singing a haunting rendition of Hoagy Carmichael’s “The Nearness of You.”

“I played this one from a boom box when Lily Rose was born,” Depp says, referring to the day a decade ago when his partner, Vanessa Paradis, the French-born singer and actress, brought their daughter into the world. “This is her birth song. She arrived to this, man.”

Welcome to Deppville. It’s a place where the off-kilter meets off-road serenity, where pure spontaneity meets fastidiously manicured fantasy.

Depp has named (his 156-foot yacht) Vajoliroja, a fairly unpronounceable construct jury-rigged from the first two letters of the names of his four family members: Vanessa, Johnny, Lily Rose, and seven-year-old Jack. The Vajoliroja has become Depp’s floating salon, garret, and getaway. The yacht has a formal dining room, a master suite, and four guest cabins. The coed crew of eight, from six nations, is quartered farther belowdecks.

The ship flies the colors of the Marshall Islands—alongside a mischievous Jolly Roger.

Our principal goal: to explore the island and reach San Juan, Puerto Rico, in time for Depp to start production on The Rum Diary.

Depp Does Dillinger

Depp has spent much of the last year living in Chicago making Public Enemies, a film about John Dillinger

Fittingly, Depp was born in Owensboro, Kentucky, 160 miles from the Mooresville, Indiana, farm where Dillinger lived as a teen. “When I was a little kid,” the actor says with a laugh, “I had no idea he was from practically next door.” While director Michael Mann, according to Depp, kept trying to get his lead to sound like some stereotypical mobster Depp had another notion. Depp dug deeper and discovered audiotapes of Dillinger’s father, John Wilson Dillinger, a farmer and grocer by trade. “The closest I could get was basically listening to his pa,” Depp said. “There were some recordings which sounded exactly like my relatives. I mean, his pop sounded like my grandfather, almost exactly. So I just made the decision to sound not aggressively southern but to adopt a bit of a drawl.”

Scenes from Public Enemies were filmed outside Stateville Correctional Center. The prison board gave Depp an impromptu tour, taking him right into the Round House, a four-story cellblock with a panopticon guard tower in the center.

“We walked in there and it was a very frightening feeling,” Depp says, becoming especially animated. “It was full lockdown. The inmates started screaming, ‘Hey, Captain Jack, get me out!’ And stuff like ‘Help me escape, Captain Jack! You can do it!’ Sh* like that. These guys went wild It was unbelievable.”

Fortuitously, a Stateville historian unearthed a mug shot of Depp’s stepfather—Robert Palmer, who died in 2000—in the prison files. For Depp, the memento was a revelation. “He’d done some burglaries, robbery—you know, that kind of thing,” Depp says. “He was in Midwest prisons from his youth up until he was a full-grown man. Yeah, so I got to learn a bit more about my stepdad and his college years, as it were.” According to Depp, Palmer was a handsome ne’er-do-well, a flinty combination of Robert Mitchum and the young George C. Scott.

Depp insists on one rule for his roles: the personalities he plays must be his imaginative creations. Each portrayal has sprung from deep within his psyche. Moreover, many of his characters exist are removed from civilization, in some parallel where fantasy, not reality, has the upper hand.

And yet when Depp plays an actual person he tries to honor their true biographies, right down to their aftershave brands, believing he might actually summon a semblance of his characters’ souls. “There’s a certain responsibility playing a guy, even Dillinger,” Depp says. “You want to do him right, ya know. You don’t want to let him down. He may be watching. So I don’t want to water down the integrity of the person I’m playing. I want to find its essence. Sometimes [period] music helps me channel.”

Although Depp, eons ago, had filmed a television episode in Chicago, Public Enemies was his first prolonged exposure to what has since become his favorite American city. “Everybody [in Chicago] treated me normal,” Depp says. “They’d say, ‘Hey, Johnny,’ then left me alone. I visited the Art Institute and the Chicago Music Exchange. I loved looking out the car window at all those incredible neighborhoods and architecture.”

Throughout the filming, Depp played Artie Shaw’s 1938 recording of “Nightmare” a dozen times a day. (This habit continued, to a lesser degree, on the Vajoliroja.) “It broke through every bad mood,” he says of the brooding and bracing song. “Somehow its power, brashness, and piercing sound helped me to stay focused.”

And to tap his inner Dillinger, he fired guns constantly. “All [of our] weapons in Chicago were taken care of by Harry Lu,” Depp explains. “He’s our genius armsman guru. We worked together on the pirate films. He’s incredibly knowledgeable. We went out to a range and tried various magazines and drums, and I got to fire live rounds out of a Thompson submachine gun for days on end. It was, I mean, a kid’s dream come true. I grew up firing guns since I was five or six years old, so for me it was like going back home.”

When I ask Depp why, like many Americans in the 30s, he cheered for the bank robber over the F.B.I., he smiles. “Come on,” he says. “You know I’m always for the Indian in the cowboy movie. Always.” Depp, who is part Cherokee, says he has been considering signing on to play Tonto in a Disney remake of The Lone Ranger. “Tonto needs to be in charge,” Depp says, half in jest. “The Lone Ranger should be a fool, a lovable one, but a fool nonetheless.”

As our voyage gets under way, Depp speaks of the need for escapism in a world gone wrong. How does the individualist, he wonders, find dignity and purity in a plastic culture and a polluted world? “Little Hall’s Pond is my decompression,” he says. “It’s my way of trying to return to normalcy. There is a period once you finish a guy—a character—when you’re looking to go back to yourself, and sometimes it can manifest illness. I mean, after I made The Libertine I was in bed for two weeks. When you’re working, you don’t get sick, then suddenly it hits you like a two-by-four. After Dillinger, my head was done in. I needed to escape. So being able to get on the boat and move allowed my head freedom again. Escapism is survival to me.

“Somehow,” he says, “the mathematics led me here to my island. I don’t think I’d ever seen any place so pure and beautiful. You can feel your pulse rate drop about 20 beats. It’s instant freedom. And that rare beast—simplicity—can be had. And a little morsel of anonymity.

“Lily Rose,” he marvels, “actually got to put a message in a bottle and watched it drift, drift away to a neighboring island, [and the finders] set up a treasure hunt for [their] kids. Whenever I was getting frustrated about being ‘novelty boy’ and making movies, I told myself, Calm down. I can come down here and disappear. I spent the Christmas season here with Vanessa and the kids. You can feed hot dogs to the nurse sharks in the Exumas—but it’s best to not swim when doing it.”

The captain of the Vajoliroja is a New Zealander named Graeme Brown, who knows the cays like a park ranger. He explains that the Land and Sea Park, near Little Hall’s Pond, is the world’s first such protected reserve, established 51 years ago. “It’s a no-take zone,” Brown says. “You can’t remove any living creatures. It’s a replenishment center for conch, lobster, and other over-harvested species.”

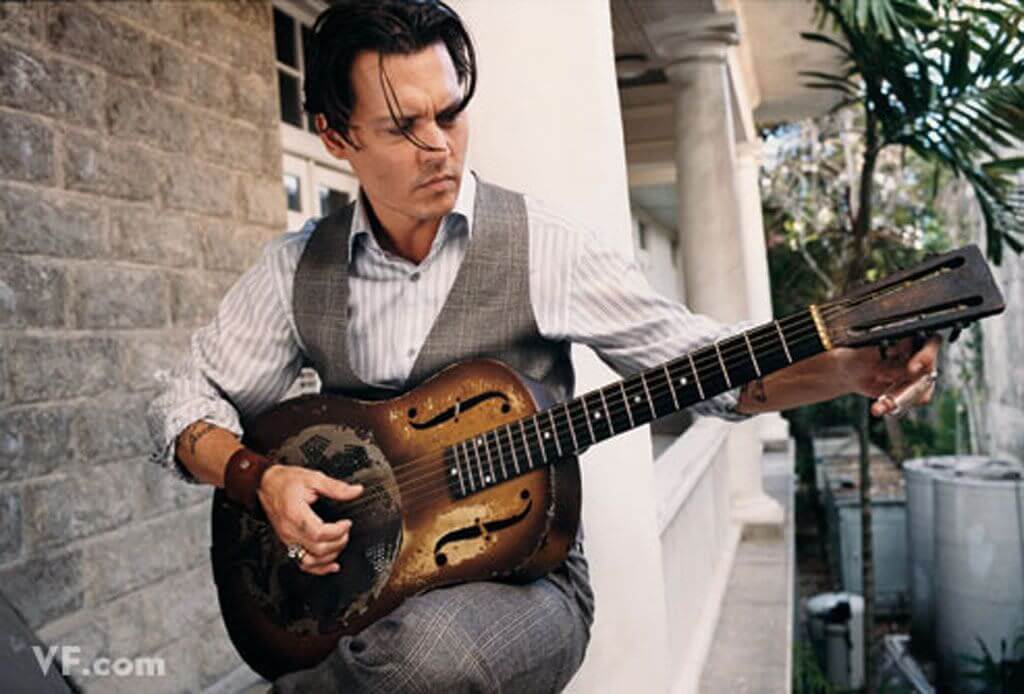

While Brown may be the captain, Depp is the commander of the ship, which he oversees like the starship Enterprise. He decides on everything from the dinner menu to the navigational route. He is also the resident mix master, programming the appropriate tune for every occasion. Die-hard rock ’n’ rollers, in fact, consider Depp an audio savant and musical talent—for his facility on guitar.

To a Tropical Oz

‘Being in a ship,” Samuel Johnson wrote, “is being in a jail with the chance of being drowned.” Depp doesn’t quite see it that way. In the vastness of the Caribbean, all of his anxieties melt away. He considers the ocean a force of strength, just as his island is his patch of sanity. In escape, he recovers and discovers and stabilizes.

Depp smoked Bali Shag tobacco like a fiend. Rolling his own had become almost a trademark for him in the 1990s. “I gave it up a few years ago,” he says. “I said, ‘F** it—I don’t need those things.’” Every morning now, Depp does yoga. He’s remarkably averse to conflict, pruning the toxic people from his life. His 48-year-old sister, Christi Dembrowski, is his closest adviser and friend. Together, they run his production company. “Basically, Christi has kept me alive,” Depp says. “I’m really like a blind mole, and she just leads me around, making me do the right thing, or I’d just fall off the cliff. She’s like Superwoman.”

Crosby, Stills & Nash are serenading us over the yacht’s speakers when we first spy Depp’s Caribbean Oz. As we approach, the water surrounding the tear-shaped isle is so clear that the land seems to be floating on the surface.

“Both our place in France and Little Hall’s Pond look as [they] probably did 100 years ago. The most satisfying part about both is their consistency.”

Little Hall’s Pond has six different beaches—Paradis, Gonzo, Brando, Lily Rose, Jack, and Utility—each with a personality and cove of its own. There are small residences scattered casually about; all are solar-powered. Transportation on the island consists of a fleet of green golf carts. “My hillbilly instinct tells me,” Depp says, “when you’re ready to drive a golf cart, you should have a beer.”

Depp directs our attention to a pocket of water 200 yards away—a prime spot for seeing tropical fish and reef plants. In the Caribbean there is a single rule: the lighter the shade of blue, the more shallow the water. Like a kaleidoscope shifting its tints of color, the waters turn from jade to sapphire, amethyst to emerald, by the hour.

Depp recalls a conversation he had with Brando in 1994, when Depp was poised to purchase Little Hall’s Pond. Instead of expressing outright enthusiasm, Brando—who once lived on the French Polynesian atoll of Tetiaroa—asked a series of pragmatic questions: “What’s the elevation? How protected are you?” Brando, according to Depp, was being sensible, focused, and paternal. “With hurricanes and all,” Depp says, “he just didn’t want me to make a mistake.”

In a quiet interlude, Depp stops and regards the sea outside. “I defy any painter,” he says, “to capture those shades of blue. I was just lucky this place found me.”

“Oh sh* A barracuda! Come look! It’s the only species more frightening than a terrier dog.” Who but Johnny Depp would consider it a form of sport to wade with the barracuda?

“Nobody is going to ever ruin the Land and Sea Park,” Depp later insists. “It’s like a rare gem, a diamond. I look forward to my kids growing up on the island, spending months out of the year here … learning about sea life and how to protect sea life … and their kids growing up here, and so on.”

One night we take the tender and head west out onto the water to witness the launch—about 300 miles away—of the space shuttle Discovery as it ascends into the evening from Cape Canaveral. The sky bulges with stars, which seem so finely etched that it’s hard to imagine the Exumas could ever experience the pitch black of a moonless night.

We wait, eyes heavenward. We wait some more. Around us, plankton causes the water’s surface to give off a gleam of eerie phosphorescence. Suddenly, a luminous cloud rises in the sky. It is shaped like an anvil, emitting the kind of incandescent gas you’d find on some distant star. The shuttle soars, in total silence, into the bejeweled black. We are transfixed by strange light, both above and below. We feel privileged to be alive in the Caribbean Basin in the Year of Our Lord 2009.

“Theoretically,” Depp says, “this place can add years to your life.” Then he quotes the old adage: “Money doesn’t buy you happiness. But it buys you a big enough yacht to sail right up to it.”

Depp tries to spend as much time with his 36-year-old partner, Vanessa Paradis, as possible—despite his acting regimen and her busy schedule as an actress, singer, model, and mother—and says he’s determined to make sure Lily Rose and Jack live like Tom Sawyers as long as they can.

Knowing his affinity for the stars of earlier eras, I ask him if there is any Hollywood icon he still hopes to spend time with. “I already met her,” he snaps. “Elizabeth Taylor.” One day actor Roddy McDowall, who knew that Depp was rather awestruck by Taylor, called him and said, “Do you want to come to dinner?” Depp attended and found Taylor to be “the best old-school dame I’ve ever met. A regular, wonderful person. Boy, did I take to her. For dinner she ordered liver and onions and just smothered them with salt. I admired that. She’s an astonishingly great broad.”

Whenever Depp gets bored or can’t sleep, he paints—specializing in oil portraits. “When I can focus on something like guitar or painting, I do,” he says. “I started painting people I admire, like Kerouac, Bob Dylan, Marlon Brando, Patti Smith, my girl, my kids. Keith Richards. What I love to do is paint people’s faces, y’know, their eyes. Because you want to find that emotion, see what’s going on behind their eyes.”

Land Ho!

After a few glorious days on the water, we approach San Juan harbor. There is no better way, I posit, to arrive in a Caribbean port city than to be flying the Jolly Roger.