Friend and rock legend Patti Smith finds him on set, guitar in hand, for a free-floating tour of the inner Depp.

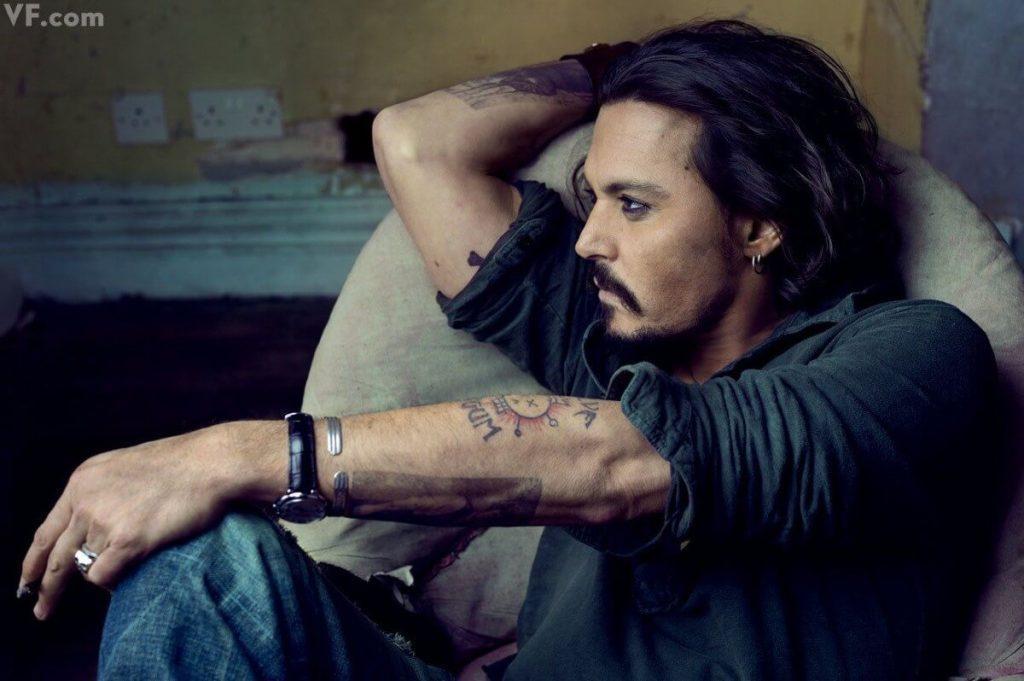

Johnny Depp is on set at Pinewood Studios, outside London, for the last days of shooting the next Pirates of the Caribbean movie—On Stranger Tides. We sit on the floor of his trailer. There is an old Stella acoustic guitar that he cannot resist picking up and strumming quietly. Johnny is working 12-hour shifts. The day begins in the makeup trailer, long before morning rush hour. Downtime is divided between press calls, stacks of pictures to sign, scripts to read, and family responsibilities—ever present and ever embraced. There is also the occasional hour of stolen sleep, often with his guitar resting on his chest.

I first met Johnny a few years ago, backstage at the Orpheum Theater, in Los Angeles, where I was performing with my band. When he laughed, I noticed his gapped teeth, a detail borrowed from the engaging smile of his companion, Vanessa Paradis, in preparation for his role as the frenetically pure Mad Hatter, in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. I had just seen The Libertine for the third time. Johnny is very likable, his magnetic energy infused with a certain shyness. In conversation, Johnny and I, both bookworms. We were dressed alike. My son, Jackson, a guitarist, who was with me, noted that Johnny seemed more like a musician than an actor.

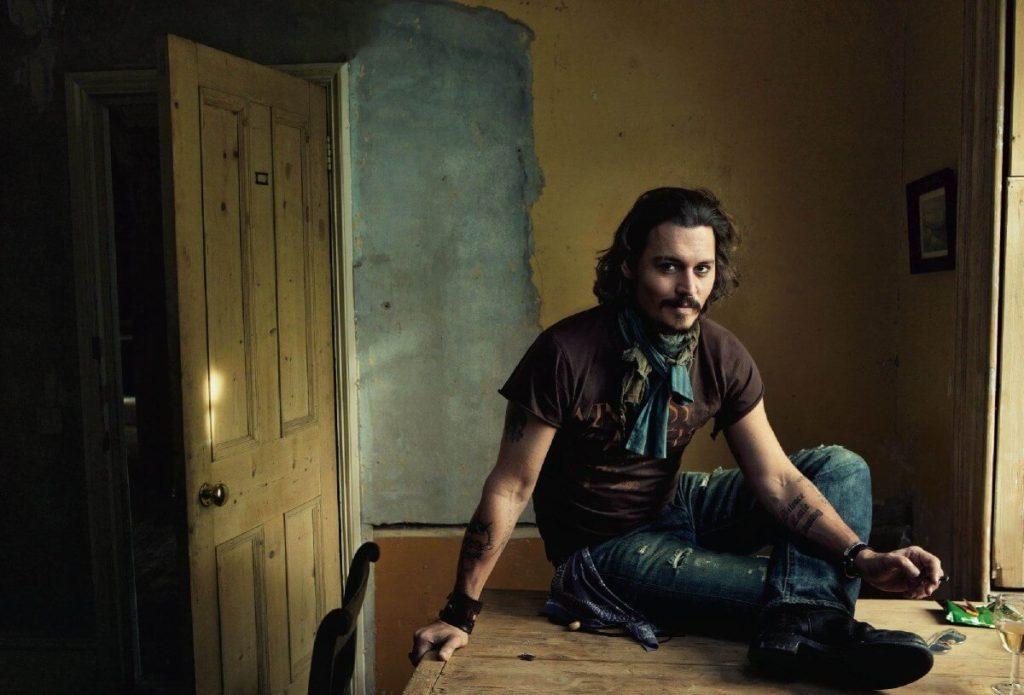

Later, visiting Johnny’s Los Angeles home, I became acquainted with his rare books and other precious objects. He never says he owns any of these things, preferring to call himself their guardian. Johnny is down to earth, yet also seems to operate in another universe. Time is precious—but also worthless. He has a bit of the Godfather in him—and also a bit of the bum. He is rebellious, as loving as the Hatter, and as ill-behaved as Jack Sparrow. He is also intensely loyal.

At the London premiere of Alice in Wonderland, I had my first glimpse of the character (from) Johnny’s new movie The Tourist. Johnny does not watch his own movies, so that night he broke ranks to say hello to fans gathered outside in the rain, later joining the celebration hosted by the whimsical genius Tim Burton. After hours, I found Johnny sitting alone in a small alcove. He was in a tuxedo. He had grown a beard, and his dark hair was longer than usual. His pale skin was illuminated by a single light, and he had thrown back his head and closed his eyes. He had left the Hatter behind and was already slipping into the interior world of Frank Tupelo. In that moment I noticed for the first time how handsome he is.

Within days of the Alice premiere he was unpacking in Venice, ensconced in a private section of a hotel tucked away at the end of a canal. The mystical light of Venice and the misadventures of Johnny and his Tourist co-star, Angelina Jolie, were about to be captured for the screen. The movie is stylish, a thrilling caper. The schedule was punishing and the weather a challenge—hot by day but very chilly for night shoots. During a midnight break we ate pizza with our coats on, then Johnny was whisked away for a long shot down a fog-shrouded canal, chained inside a water taxi. Angelina awaited her cue, a hooded parka concealing the glamour that would soon emerge. Brad Pitt was minding the children, but her mother radar was always on. Paparazzi were kept at bay, but hovered relentlessly.

Now, in London, as winter sets in, Johnny is again consumed by Captain Jack. Johnny’s boy, Jack, who has the gaze of his mother and the stance of his father, accompanies the Captain on set, but not until jacket, cap, and scarf are located. It is damp and chilly, and the scene I witness is a mix of swordplay and slapstick. Afterward, the dresser takes away the Captain’s locks—a heavy tangle of dreads and bones. Johnny’s dark silky hair is held flat in tight braids. There is a set change and a lull, so we sit on the floor of the trailer, a rare moment of peace, with his boy safe at hand. He smiles a smile that is his own. He is just Johnny, and, in truth, Johnny is character enough.

Smith: Anytime I’ve seen you—in a trailer, at your home, in a hotel room—you always have at least one guitar with you. You sometimes talk while strumming a guitar. How connected are you with music?

Depp: It’s still my first love as much as it ever was, since I was a little kid and first picked up a guitar and tried to figure out how to make the thing go. Going into acting was an odd deviation from a particular road that I was on in my late teens, early 20s, because I had no desire, no interest, really, in it at all. I was a musician and I was a guitarist, and that’s what I wanted to do.

But because of that deviation, and because I don’t do it for a living, maybe I still have been able to maintain that kind of innocent love for it. The weird thing is I think I approach my work the same way I approached guitar playing—looking at a character like a song. If you think of expression musically—it goes from wherever it comes from inside to your fingers, and on to that fretboard, and then on to the amplifier, through whatever. It’s the same kind of thing that’s required here, with acting: What was the author’s intent? What can I add to it that maybe someone else won’t add to it? It’s not necessarily a question of how many notes, but a question of what do the notes express and what does a slight bend do.

I overheard someone in your camp talking about how eager you were to get back to Captain Jack, and about how much Jack was like you. How do you feel when you enter into the skin of Captain Jack?

Free — free to be irreverent. I think it’s like unlocking a part of yourself and freeing this part of yourself to just be, under whatever circumstances.

“Somebody once asked [Hunter Thompson], “What is the sound of one hand clapping, Hunter?” and he smacked him. Captain Jack was kind of like that for me, an opening up of this part of yourself that is somewhat—you know, there is a little Bugs Bunny in all of us.

Young kids love—really love—the Captain. And who is more mystically mischievous, and brilliant in his own way, than Bugs Bunny?

At the time, I had been watching nothing but cartoons with my daughter—with Lily Rose. I hadn’t seen a grown-up film in forever. It was all cartoons, all those great old Warner Bros. things. And I thought, the parameters here are so much wider and more forgiving in terms of character. These cartoon characters could get away with anything. And I thought, They’re beloved by 3-year-olds and 93-year-olds. How do you do that? How do you get there? That was kind of the start.

I also see a little bit of John Barrymore in Captain Jack. There’s humor and often a feyness. He keeps his intelligence in his own little treasure chest. He doesn’t really want people to comprehend that he knows everything.

He has already assessed the situation.

What were you reading to inform you about Captain Jack’s life, or his lifestyle?

I was reading a lot of books about early pirates. There was one book in particular that was really helpful called Under the Black Flag. You realize that those guys were—you either loved it or you were press-ganged and you didn’t. One of the things that helped me most with Captain Jack was a book by Bernard Moitessier, and it’s where I found the last line for the first Pirates movie. The writers were stumped, and they’d say, Well, what about this? And nothing seemed to click. I was reading this Moitessier book on sailing the earth, and he had written about how the ultimate for a sailor was the horizon, and to be able to attain that horizon, which you never get to, which is why it keeps pushing you forward. I thought, That’s it! That’s it! So I went to them and said, I’ve got a line for you: “Bring me that horizon.” And they looked at it and went, Nah, that’s not it. But about 45 minutes later they came to me and went, That’s the line.

Because delivered in a certain way …

Yeah—“Bring me that horizon.” That’s what they all want. That’s what all those guys want. Get me that horizon. And you never get there.

How did Disney feel about Captain Jack? He does have a wisp of controversy about him.

It was a totally different regime over there at the time. They couldn’t stand him. They just couldn’t stand him. I think it was Michael Eisner, the head of Disney at the time, who was quoted as saying, “He’s ruining the movie.” It was that extreme—memos, and paper trails, and madness, and phone calls, and agents, and lawyers, and people screaming, and me getting phone calls direct from, you know, upper-echelon Disney-ites, going, What’s wrong with him? Is he, you know, like some kind of weird simpleton? Is he drunk? Is he this? Is he that?

The role of Frank in The Tourist is so different from the Hatter or the Captain—more subtle. Characters like him—who seem to have less that you can grasp—I would think would be harder to do.

The great challenge of a character like Frank, for me, is that he’s Everyman, you know, Mr. Ordinary—not a simpleton, just ordinary. He’s a math teacher. I was always fascinated by people who are considered completely normal, because I find them the weirdest of all.

So where did you find Frank?

He was sort of a combo platter for me, from certain people I’ve known over the years. I knew an accountant who would travel—he was super-straight, very, very straight guy—and he would travel all over the world to photograph places that had street signs or businesses that had the same name as his last name. He’d go to Italy, he’d go to Shanghai, and he’d take photographs. That was his kick.

He had an eccentricity that no one sees. Everyone sees the eccentricities of an artist. But eccentricities like Frank’s are so subtle and so particular.

It was guys like that that I thought about. Frank, for example, who had quit smoking, could be absolutely fascinated with that electronic cigarette, and the moving parts of it, and being able to really explain it to someone in great detail.

“Daydream Believer” came on the radio when we were driving to the set. It was a moment of total happiness. It’s a pure, happy little song. What bad thing can you say about it?

Oh, “Daydream Believer.” It’s a great song. I don’t care what anyone says. It’s O.K. to like “Daydream Believer.” There’s nothing wrong with a guilty pleasure from time to time. Know what I mean? It’s “Daydream Believer.” I’m justifying my own flag.

Getting back to The Tourist, from what I saw, on set, the atmosphere seemed fraught with mischief.

Angelina — we’d met basically on this film. Meeting her and getting to know her was a real pleasant surprise, and I say that with the best meaning, just in the sense that she’s this quite, you know, famous, and, I mean, poor thing, dogged by paparazzi, her and her husband, Brad, you know, and all their kids, and their wonderful life, but they are plagued by … so you don’t know what to expect, really. You don’t know what she might be like—if she has any sense of humor at all. I was so pleased to find that she is incredibly normal, and has a wonderfully kind of dark, sense of humor. And because here we are working together in this situation where you could really—there are times when you see how ridiculous is this life, how ludicrous it is, you know, leaving your house every morning and being followed by paparazzi, or having to hide, sometimes not even being able to talk to each other in public because someone will take a photograph and it will be misconstrued and turned into some other sh*.

On set, I told her that she looked beautiful, and she explained to me about all the different people it takes to make that possible—as if she really isn’t. I found Angelina interesting. If you talk about her beauty, she scoffs. If you mention a cause, she invites you to take a stand.

That’s the thing with Angie. I mean, you look at her and you go, O.K.: “goddess,” “movie icon.” In 30 years people will still be going, “Oh, my!” Elizabeth Taylor kind of territory. And she has got that, no question about it. But, like anything, it’s the way she deals with it. She’s so down to earth, and so bright, and so real. I’ve had the honor and the pleasure and gift of having known Elizabeth Taylor for a number of years. Who’s a real broad. You know, you sit down with her, she slings hash, she sits there and cusses like a sailor, and she’s hilarious. Angie’s got the same kind of thing, you know, the same approach.

Something I’ve always wondered about is: these people that you become for us, or make flesh in a film—do they revisit you ever? Are you able to discard them? What happens to them?

They’re all still there, which on some level can’t be the healthiest thing in the world. But, no, they’re all still there. I always picture it as this chest of drawers in your body—Ed Wood is in one, the Hatter is in another, Scissorhands is in another. They stick with you. The weirdest thing is that I can access them. They’re still very close to the surface.

It must be difficult when you have multiple personalities in one of them, like the Hatter has. What does he say, “It’s crowded in here”?

“I don’t like it in here. It’s terribly crowded.” But they all, somehow, have their place. They have come to terms with each other, I suppose.

When you’re playing someone—when you’re really deep within a character—have you ever had a dream that you felt was not your dream? Do your characters dream within you?

I’ve certainly had dreams where I was the character. Sweeney was like that. There were a lot of dark Sweeney dreams.

Do you have any actors that you studied from the past, actors from any era, who were helpful either in a specific role or just in general?

The guys I always adored were mostly the silent-film actors, Buster Keaton first, and Chaplin, of course. And John Barrymore.

But Marlon, it wasn’t until Marlon Brando came along that it was revolutionary, it just changed everything. The work he was doing, Streetcar — completely different f**ing animal. And everybody changed their approach from that moment on.

He was bigger than—I don’t know how to say it—it was almost like the screen could not contain him. Does that make sense?

Absolutely. I don’t know what it is, or was, but, at that time—especially at that time—he had too much. And the shape of his face and his nose and his—and the distance between his forehead and his eyebrows, and whatever was going on for whatever genetic reason, or whatever. He was placed in that spot for that particular thing. And, man, he cranked it. He just absolutely owned it.

It’s interesting when one individual—whether it’s Michelangelo, Coltrane, Bob Dylan—they’re so inspiring, and they help beget almost a whole school, but no one can touch them. They have this place of kingship, but also solitude.

And Marlon hated it. He hated it, which is probably why he rejected the whole idea of it, you know, and made fun of it. But I know it’s bullsh*. I know he was capable of the work and worked hard when he did the work. I saw him do it, you know. He did care.

Earlier, you mentioned those greats, the silent-film greats. You’re a master of language, voice, script, words. And yet you chose silent-film actors.

The amazing thing about those guys is that they didn’t have the luxury of language. So what they were doing, what they were feeling, what they were trying to express, had to come out through being, had to be alive, had to be in there behind the eyes. Their body had to express it, their very being had to express it.

Throughout your life you seem to have had beautiful relationships with a succession of mentors—Marlon, Allen Ginsberg. You hold these people with you. Is that something that has just come your way? Or is it something that you seek in life?

I think it’s probably a combination. It’s never been a conscious sort of searching, but it did happen with these guys. The combination probably goes back to memories of my grandfather. We were very, very close, and I lost him. I was about nine.

Is it your grandfather you have tattooed on your arm?

Yeah, Jim. He was a wonderful model. He drove a bus during the day and ran moonshine at night. He was a Robert Mitchum type, a man’s man. He just said things as they were. He’d call a spade a spade—and piss on you if you don’t like it. He was also of a different era—I mean, a radically different era, as were some of the other guys that we’ve talked about, like Marlon and even Keith [Richards] to some degree, and Allen certainly. I really believe it was a better time. I really believe that, at a certain point, if you’re born in ’60-something or whatever, you got ripped off—you know what I mean? I always felt like I was meant to have been born in another era, another time.

I was thinking back on Edward Scissorhands—he has this father figure and mentor, Vincent Price’s character. You told me a story once about Vincent Price.

We were doing Scissorhands and Vincent was playing the inventor—essentially my father in the film. And he was a decent man. He was able to move around. He was cool. He was old.

Was that his last film?

I think it was, yes. I think it was his last.

Such a beautiful film to end with.

And the same kind of genre that he dwelled in for a long time. I adored him. As did Tim, a long time before me. So we spent time together, hung out. I was totally enamored. And I had this volume of Edgar Allan Poe, Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Do you ever think of doing plays? I think it would be wonderful to see you work live.

I do, I do, I do. The bitter pill that I swallowed was with Marlon, who asked how many movies I did a year. And I said, I don’t know—three? He said, You ought to slow down, kid. You’ve got to slow down ’cause we only have so many faces in our pockets.

And then he went on to say, Why don’t you just take a year and go and study Shakespeare, or go and study Hamlet. Go and work on Hamlet and play that part. Play that part before you’re too old. I thought, Well, yeah, yeah, I know Hamlet. Great. What a great part, great play, you know, this and that.

And then the killer came. He said, “I never did it. I never got the chance to do it. Why don’t you go and do it?” He was the one that should’ve done it, and he didn’t. He didn’t. So what he was trying to tell me was: play that f**ing part, man. Play that part before you’re too long in the tooth. Play it. And I would like to. I’d really, really like to.